The land between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates, known as Mesopotamia, has often been described as the cradle of civilization. Here, among fertile floodplains and under vast skies, some of the earliest cities emerged—Uruk, Ur, Babylon, Nineveh. Along with writing, law, and monumental architecture, Mesopotamia gave the world something equally enduring: its myths. These ancient stories are not merely relics of a distant past. They are humanity’s first recorded attempts to explain life, death, the origins of the cosmos, and the turbulent relationship between humans and the divine.

Among the most compelling of these myths are the creation stories and flood legends. They are tales of gods who fought and loved, of worlds shaped from chaos, of waters that both nourished and destroyed, and of human beings struggling to find meaning under the watchful eyes of higher powers. They are stories that echo through time, influencing later traditions, including those found in the Hebrew Bible, the Greek world, and beyond. To explore Mesopotamian myths is to step into the collective imagination of one of humanity’s earliest cultures—a place where cosmic battles birthed order and where floods could erase humanity in a single sweep.

The Worldview of the Mesopotamians

Before delving into the myths themselves, it is important to understand the worldview of the people who created them. Life in Mesopotamia was defined by cycles of abundance and destruction. The rivers were both life-giving and deadly, capable of irrigating fields and sustaining cities but also prone to devastating floods. The natural environment shaped a vision of the universe where stability was always precarious, where chaos threatened to return at any moment, and where gods wielded immense, often unpredictable power.

To the Mesopotamians, the gods were not distant, abstract beings but active participants in the world. Each city had its patron deity, and divine will was believed to be reflected in every harvest, every storm, every war. Humanity was not seen as the pinnacle of creation but as a servant class, made to provide labor, food, and worship for the gods. Within this framework, myths served as more than entertainment—they were explanations, justifications, and warnings. They revealed why the world was as it was and what might happen if the delicate balance between gods and humans was disturbed.

Creation from Chaos: The Enuma Elish

Perhaps the most famous Mesopotamian creation story is preserved in the Babylonian epic known as the Enuma Elish, which means “When on High,” after its opening line. This myth was recited during the New Year festival in Babylon, a time of renewal when chaos threatened to reassert itself, and order had to be ritually reaffirmed.

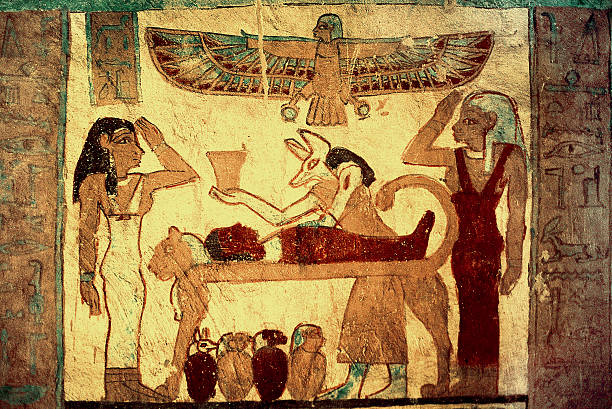

The Enuma Elish begins not with a void, but with waters mingling. There were two primordial beings: Apsu, the fresh water, and Tiamat, the salt water. From their union sprang the first generation of gods. But as the younger gods grew noisy and restless, Apsu plotted to destroy them. The plan was discovered, and Ea (also called Enki), a clever and powerful deity, killed Apsu. Tiamat, enraged and grieving, became the embodiment of chaos itself. She birthed monsters—serpents, dragons, scorpion-men—to wage war against the younger gods.

It was then that Marduk, a rising god of Babylon, offered to fight Tiamat. In exchange, he demanded supreme authority over the pantheon. Armed with a net, bow, and arrow, Marduk confronted Tiamat in battle. With skill and strategy, he caught her in his net, pierced her heart with an arrow, and split her body in two. From one half he created the heavens, from the other the earth. Marduk then organized the cosmos: he set celestial bodies in motion, measured time, and established order where chaos once reigned.

Finally, to relieve the gods of toil, Marduk fashioned humanity. He used the blood of Kingu—Tiamat’s chosen commander—to create mankind, destined to serve the gods by providing offerings and labor. Thus, humanity was born not as divine companions but as workers in the service of higher powers.

The Enuma Elish is not only a creation story; it is a political and theological text. By placing Marduk at the center, it elevated Babylon and its deity above other cities and gods. The myth reflects the Mesopotamian conviction that order is won through struggle, that chaos is never far away, and that human beings exist to sustain the fragile balance between the divine and the earthly.

Other Mesopotamian Creation Myths

Though the Enuma Elish is the most complete surviving creation story, other Mesopotamian traditions provide different perspectives. In Sumerian myths, the goddess Nammu, the primeval sea, was sometimes credited with giving birth to the heavens and the earth. Her children, An (sky) and Ki (earth), then produced Enlil, the storm god who separated them and gave space for life to flourish.

In another account, the god Enki played a central role in shaping humanity, forming people from clay and infusing them with the divine spark of life. This motif of humans made from clay resonates with later traditions in the Hebrew Bible and in Greek mythology, suggesting that Mesopotamian myths seeded ideas that spread widely across the ancient world.

Each variation underscores a core theme: the world emerged from watery chaos, and the gods brought order through acts of separation, creation, and sometimes violence. Humanity, regardless of the details, always entered the stage as subordinate to divine will.

The Flood: Humanity’s Near-Erasure

If Mesopotamian creation myths explain the beginnings of the world, their flood legends describe its near-endings. These tales of deluge are among the most striking and influential of ancient narratives, paralleling stories in the Hebrew Bible, Indian traditions, and even far-flung cultures across the globe.

The most famous Mesopotamian flood story appears in the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of humanity’s earliest surviving literary masterpieces. In this epic, the hero Gilgamesh seeks the secret of immortality and meets Utnapishtim, a man who survived a great flood sent by the gods.

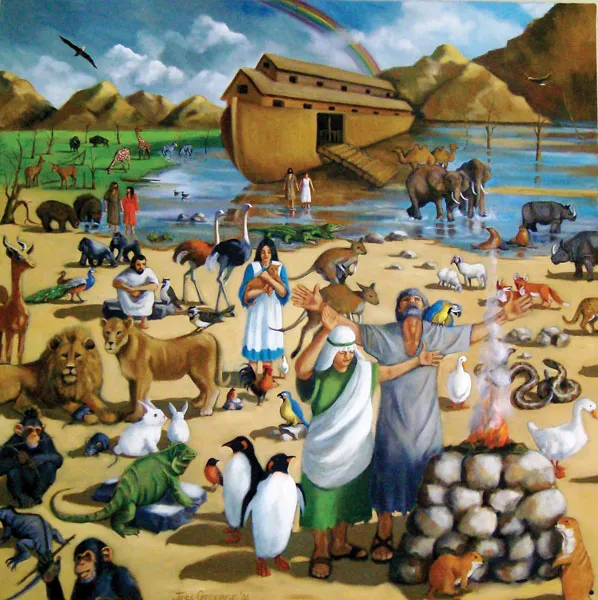

According to Utnapishtim, the gods had grown weary of humankind’s noise and disobedience. Enlil, the storm god, resolved to wipe them out with a flood. Yet Ea, the god of wisdom and craft, took pity on one righteous man—Utnapishtim. Speaking through the walls of his house, Ea warned him to tear down his dwelling and build a massive boat. Utnapishtim was instructed to take aboard his family, craftsmen, animals of every kind, and provisions for survival.

When the flood came, it was catastrophic. The storm raged for six days and nights, submerging the land. On the seventh day, silence fell, and Utnapishtim’s boat rested on a mountain. To test whether the waters had receded, he released a dove, then a swallow, and finally a raven. The raven did not return, confirming that dry land had appeared. Utnapishtim offered a sacrifice, and the gods, smelling the pleasing aroma, regretted their destruction. Enlil, though angered that anyone survived, was calmed, and Utnapishtim was granted immortality as a reward for his obedience and faithfulness.

This flood narrative bears striking resemblance to the story of Noah in the Book of Genesis. Both feature a divine warning, the construction of a great vessel, the preservation of animals, the release of birds, and a sacrificial offering after the waters recede. Scholars debate whether the Hebrew story drew directly from Mesopotamian sources or whether both traditions reflect a shared cultural memory of catastrophic floods in the ancient Near East. What is clear is that the Mesopotamian version predates the biblical account by centuries, making it one of the earliest recorded flood legends in human history.

The Sumerian Flood Story

Even before the Epic of Gilgamesh, Sumerian texts recorded flood myths. The Sumerian King List, an ancient document combining history and legend, declares that kingship was first “lowered from heaven” before a flood swept over the land. After the deluge, kingship was reestablished in new cities, marking a fresh beginning for humanity.

Another Sumerian text tells of Ziusudra, a righteous king chosen by the god Enki to survive the flood. Much like Utnapishtim, Ziusudra built a great boat, preserved life, and offered sacrifices after the waters subsided. The parallels between Ziusudra, Utnapishtim, and Noah reveal a continuity of flood traditions across Mesopotamian cultures and their deep influence on later mythologies.

Symbolism of the Flood

What do these flood stories mean? At one level, they may reflect memories of real floods in Mesopotamia, where the unpredictable Tigris and Euphrates rivers could devastate settlements. Oral traditions could have magnified such events into myths of cosmic destruction.

On a symbolic level, the flood represents divine displeasure and the fragility of human existence. It is a reset button, a way for gods to erase mistakes and start anew. Yet the survival of a chosen individual—Utnapishtim, Ziusudra, or Noah—also suggests a thread of hope, that even in judgment, mercy and continuity prevail.

The flood myths remind us of the Mesopotamian view of life: precarious, at the mercy of forces beyond human control, yet never entirely without possibility of renewal.

Human Purpose in the Myths

Across both creation and flood stories, one message is clear: humans exist for the gods. In the Enuma Elish, people are made from the blood of Kingu to relieve the gods of labor. In the flood myths, humanity’s noise and excess trigger divine wrath. Yet even after destruction, humans are preserved—not for their own sake, but to continue serving the divine order.

This vision may feel harsh compared to modern notions of human dignity and autonomy. But for the Mesopotamians, surrounded by uncertainty, it offered a framework for understanding suffering and survival. To serve the gods was to find meaning, and to maintain order was to stave off chaos.

The Legacy of Mesopotamian Myths

Though the civilizations of Mesopotamia eventually fell, their myths endured, leaving a profound legacy. They influenced neighboring cultures, including the Hebrews, Greeks, and Persians. Elements of the Enuma Elish echo in the Genesis creation account, where order is brought out of watery chaos. The flood narrative of Utnapishtim parallels the story of Noah so closely that direct cultural borrowing seems undeniable.

Beyond specific parallels, Mesopotamian myths shaped the way later civilizations thought about divine power, human purpose, and the fragile boundary between order and chaos. They are among humanity’s earliest explorations of universal questions: Why are we here? What do the gods want from us? Why do disasters happen? Can life begin again after destruction?

The Emotional Power of the Myths

What makes these stories endure is not only their historical significance but also their emotional resonance. The tale of Tiamat’s chaos and Marduk’s triumph speaks to our eternal struggle to bring order out of disorder. The flood myths stir deep emotions of fear, loss, and hope—the terror of annihilation balanced by the relief of survival. Even today, when we read of Utnapishtim’s boat resting on a mountain, we feel the same sense of renewal that ancient listeners must have felt, the reassurance that even in devastation, life persists.

These myths also remind us of humility. They show humanity not as masters of the universe but as small, fragile beings, utterly dependent on forces beyond control. In a modern age where technology often gives us the illusion of power, the Mesopotamian worldview is a sobering reminder of nature’s might and life’s precariousness.

Conclusion: Ancient Stories, Timeless Questions

The creation stories and flood legends of Mesopotamia are not merely ancient curiosities; they are part of the living heritage of human thought. They offer windows into the fears, hopes, and wisdom of the world’s first civilizations. They speak of chaos and order, destruction and renewal, human frailty and divine power.

To study these myths is to encounter the beginnings of storytelling as a tool for survival, meaning, and identity. They shaped religions, inspired literature, and continue to echo in modern imaginations. Beneath their ancient names—Apsu, Tiamat, Marduk, Utnapishtim—we hear timeless themes: the chaos that surrounds us, the fragile gift of life, and the eternal question of what it means to be human in a world shaped by forces greater than ourselves.

Mesopotamian myths remind us that the search for meaning did not begin with us. It began thousands of years ago, on the banks of two rivers, where human beings first lifted their eyes to the heavens and asked how the world came to be, and whether it might one day be washed away.