In the rugged wilds of Scotland’s Isle of Skye—where the mountains meet the sea in an elemental dance—an extraordinary archaeological discovery is rewriting the story of prehistoric human survival in the far north. Led by a team from the University of Glasgow, researchers have unearthed a site at South Cuidrach that bears unmistakable hallmarks of the Ahrensburgian culture. This represents the most northerly evidence of that culture in Britain and a rare glimpse into the resilience of Late Upper Paleolithic communities.

The Ahrensburgian Legacy: Reindeer Hunters of the Ice Age

The Ahrensburgian culture, originating in northern Europe toward the end of the Upper Paleolithic, is known for its specialized stone tools—particularly tanged points, blades, and burins. These were the implements of reindeer hunters, forged during one of the most inhospitable climatic episodes of the past 15,000 years: the Younger Dryas.

This period, spanning roughly from 12,900 to 11,700 years ago, was marked by a sudden and intense return to glacial conditions. As ice sheets surged across northern Europe and sea levels plummeted, life for human populations became harsh and uncertain. Archaeologists long assumed that Scotland, especially its western reaches, was simply too cold and unstable for humans to persist. The new evidence from Skye radically alters that narrative.

South Cuidrach: An Unexpected Footprint

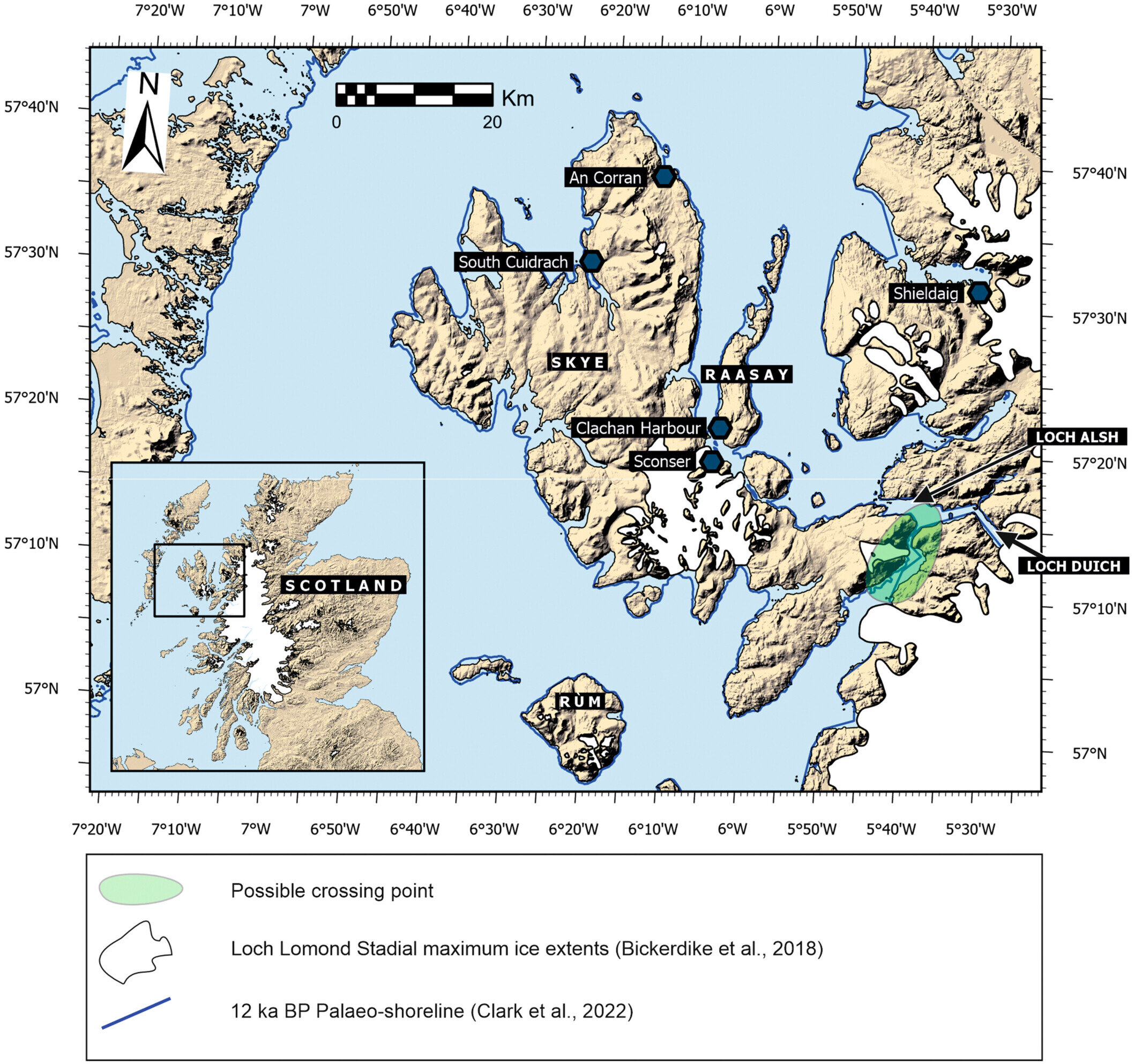

Tucked into the far northern edge of Skye, South Cuidrach was once overlooked as an unlikely spot for ancient human occupation. Today, it is a site of major significance. Excavations across a 30-square-meter area revealed a scatter of lithic tools characteristic of Ahrensburgian technology. These include tanged points—stone projectiles shaped like arrowheads with a distinct stem for hafting—as well as fine blades, chisels (known as burins), and scrapers.

The total lithic assemblage counts 196 artifacts, mostly crafted from a locally abundant baked mudstone. That consistent use of raw material suggests not just a fleeting visit but knowledge of the land—perhaps even repeated seasonal habitation.

Though no direct radiocarbon dates could be obtained from the Ahrensburgian artifacts, they were discovered in association with Mesolithic layers. Stratigraphic analysis places them within the window of the Younger Dryas or immediately after—meaning that these humans were operating on Skye during or just following one of the most brutal climatic downturns in prehistory.

A Second Mystery: The Sconser Stone Circles

Even more intriguing, however, is what researchers found nearly 40 kilometers to the southeast at Sconser. Here, in the intertidal zone—visible only during the lowest tides—lie up to 20 circular stone alignments, each spanning 3 to 5 meters in diameter. These boulder rings sit 1.83 to 4.14 meters below modern sea level, submerged remnants from a time when the ocean’s reach was far less intrusive.

No tools or bones have been found within the circles, and no direct radiocarbon dates were possible. But comparative studies, particularly with similar submerged features in Norway, point to an Early Holocene construction date—placing them squarely in the same cultural and temporal frame as the Ahrensburgian materials from South Cuidrach.

Were these stone circles the remnants of dwellings? Fish traps? Tidal hunting structures? Their submerged locations suggest that, if they were used by people, those people lived in a landscape vastly different from the one we see today. A Scotland not just colder, but drier and more expansive, with shorelines stretched far beyond current boundaries.

Crossing Ice-Age Frontiers: From Doggerland to Skye

The Ahrensburgian culture is generally believed to have originated in what is now northern Germany, Denmark, and the Low Countries. During the Late Upper Paleolithic, the landmass now submerged beneath the North Sea—Doggerland—was a vast plain connecting Britain to the European mainland. This natural land bridge enabled the movement of humans, animals, and technologies between the continent and what would later become the British Isles.

From there, it’s believed that these hardy reindeer hunters moved westward, possibly following game and the rhythms of the seasons. Reaching Skye would have been no small feat. Even during periods of low sea level, the Kylerhea Narrows separated the island from the Scottish mainland by a narrow but treacherous stretch of water. But if these people could track migrating herds across frozen tundra, it’s plausible they also developed methods for short sea crossings—especially when sea levels were dozens of meters lower than today.

The artifacts at South Cuidrach suggest they made it. And that they may have returned more than once.

Rewriting the Human Timeline of Scotland

For much of the 20th century, the dominant view among archaeologists held that Scotland was largely uninhabitable during the Younger Dryas. While isolated lithic finds on the mainland hinted at brief occupations, none were convincing enough to indicate persistent or meaningful human presence.

That began to change in the past two decades. As excavation methods improved and interdisciplinary approaches combined archaeology with climate science and sea-level modeling, researchers began to spot subtle clues. The discoveries on Skye—especially the Ahrensburgian toolkit and the Sconser stone circles—now stand as some of the clearest evidence that humans not only survived but possibly thrived in Scotland during this frigid chapter of prehistory.

These people adapted to a world in flux. They found ways to endure the cold, to source food and raw materials, and to leave behind hints of their ingenuity for us to uncover millennia later.

The Science Behind the Discovery

The research team employed a range of modern techniques to interrogate the sites. Systematic test pitting at South Cuidrach helped define the horizontal and vertical distribution of artifacts. Drone surveys generated high-resolution elevation data and orthomosaic maps that revealed subtle changes in topography and site structure.

Meanwhile, bathymetric and elevation data from Sconser were used to estimate the sea-level conditions when the circular alignments were constructed. The findings suggest these stone circles would have been built during a time when the sea was several meters lower than today—likely between 10,000 and 8,000 years ago.

Though direct dating remains elusive, the contextual data—the tool types, the stratigraphy, the geomorphology—all converge to point toward a Late Upper Paleolithic and Early Holocene timeframe.

Echoes Beneath the Waves

Perhaps the most tantalizing implication of the Sconser site is what may lie beyond it—further offshore, beneath the cold waters of Skye’s coastal shelf. If these intertidal stone structures are the edge of a submerged settlement, what else might be waiting to be found?

As global sea levels rose rapidly at the end of the last Ice Age, vast tracts of prehistoric coastlines were drowned. Some archaeologists now speculate that the richest Paleolithic and Mesolithic sites in Britain may be lost beneath the ocean. Advances in underwater archaeology and remote sensing may one day reveal their secrets.

A Population that Endured

In the end, what makes the Skye discovery so compelling is its human dimension. The tanged point found at South Cuidrach is more than just a piece of sharpened stone. It is a fingerprint from a time when the odds of human survival were vanishingly small.

These Ahrensburgian people were not merely visitors—they were adapters, explorers, and survivors. They crossed ancient plains, braved new frontiers, and reached what would have seemed, to many, the edge of the world. And yet, for them, it was home.

In the language of the researchers, Skye was “the far end of everything.” But in truth, it was just another chapter in the great human journey. A journey that—despite ice, ocean, and oblivion—continues to surprise us.

Reference: Karen Hardy et al, At the far end of everything: A likely Ahrensburgian presence in the far north of the Isle of Skye, Scotland, Journal of Quaternary Science (2025). DOI: 10.1002/jqs.3718