High in the rugged mountains of Europe, Asia, and northeastern Africa, a wild and graceful creature climbs sheer cliffs with impossible ease. This animal, the ibex, a species of wild goat belonging to the genus Capra, has lived alongside humans for tens of thousands of years. To early communities, the ibex was not just a source of food or a potential ancestor of the domestic goat—it was a living symbol. Its curved horns, seasonal behaviors, and mountain-dwelling nature made it a powerful figure in myths, rituals, and art across the ancient world.

A new study published in L’Anthropologie by Dr. Shirin Torkamandi, alongside Dr. Marcel Otte and Dr. Abbas Motarjem, explores the deep symbolic meaning of the ibex in the ancient Near East. Their research reveals how this animal became intertwined with ideas of fertility, femininity, rain, and even the stars, leaving an enduring mark on human culture from prehistory to early civilizations.

From Wild Goat to Domestic Companion

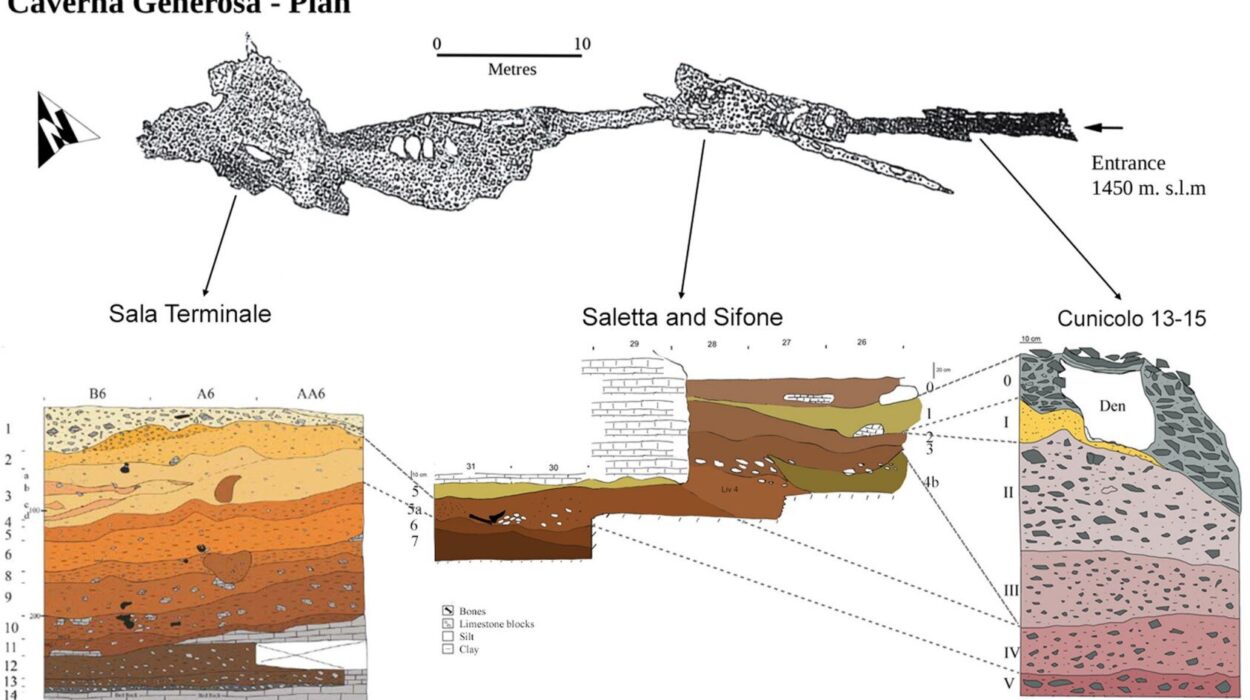

The ibex has long been both a real animal and a symbolic figure. Genetic studies of mitochondrial DNA suggest that wild ibex were first domesticated around 10,000 years ago in the Zagros Mountains of Iran and Eastern Anatolia. From this domestication came the domestic goat, an animal that would go on to play a crucial role in human survival, providing milk, meat, hides, and companionship in farming life.

But before domestication, the ibex was already deeply embedded in human imagination. Hunters and early farmers painted its form on cave walls, carved it into stone, and later etched it onto pottery and metalwork. This repetition across cultures and centuries suggests that the ibex was never just an animal of utility—it carried symbolic weight, linking the earthly, the divine, and the cosmic.

The Ibex and the Feminine Principle

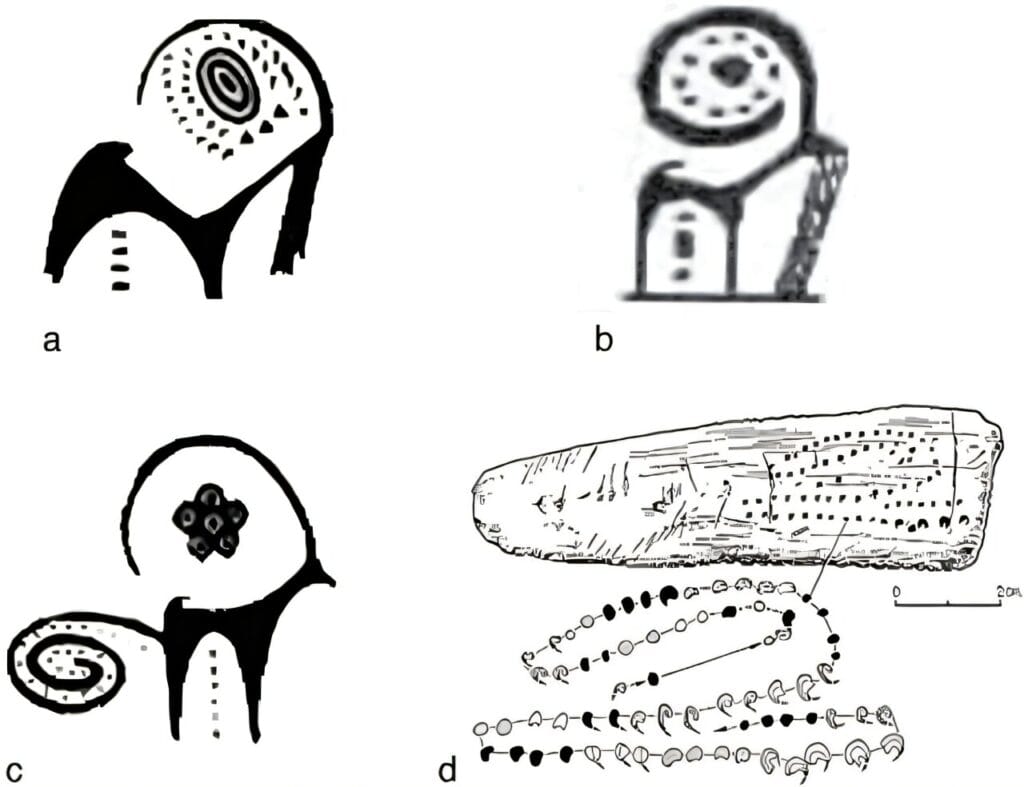

One of the most striking findings of the study is the recurring connection between the ibex and symbols of femininity and fertility. Across Europe and the Near East, ancient depictions of ibexes appear alongside female figures and fertility motifs.

In the famous Laussel rock shelter in France, a Venus-figured woman—characterized by exaggerated breasts, hips, and abdomen—holds what appears to be an ibex horn. Similarly, in the Mother Ranaldi rock art, ibexes and deer are drawn around a central figure interpreted as a woman giving birth. The message is clear: the ibex was tied to ideas of reproduction, the cycles of nature, and the power of life itself.

This symbolism carried into the Near East as well. The Babylonian goddess Inanna, associated with fertility and sexuality, famously refers to her vulva as a “horn.” Archaeological evidence also shows images of ibexes or deer painted on the bodies of female mummies during the Achaemenid-Scythian period, further linking the animal with feminine power and the mystery of creation.

Enki, the Rain God, and the Calendar of the Ibex

In Mesopotamian culture, the ibex also became linked to fertility through water and rain. The Sumerian god Enki, who presided over fresh water, rivers, and fertility, is often depicted together with goats or ibexes. This association may not have been accidental but grounded in the rhythms of nature.

The mating season of the ibex occurs in October and November—precisely the time of the rainy season in Mesopotamia. To ancient farmers, this synchronicity may have seemed divine: as the ibexes bred, the land too was “fertilized” by rains that nourished crops and sustained life. Thus, the ibex became a kind of natural calendar, its behaviors mirroring the rhythms of the environment and shaping religious meaning.

A Bronze Plaque and a Shared Symbol

The study points to powerful archaeological evidence supporting this symbolism. A bronze plaque from eastern Iran, dating between 1500 and 700 BC, depicts two ibexes surrounding a woman giving birth. The image echoes the much older Mother Ranaldi rock art, suggesting that this symbolic association persisted across thousands of years and different cultural contexts.

Such continuity is remarkable. It suggests that the ibex carried a deeply rooted symbolic charge, one passed on through collective memory, shared rituals, and artistic traditions across Eurasia.

The Star-Horned Goat

The symbolism of the ibex extended beyond fertility and into the skies. In Mesopotamian and Iranian traditions, the ibex was linked with celestial bodies and the heavens. The Sumerians called it si-mul, meaning “star-horned” or “bright-horned.” Its majestic horns, curving like crescents, likely evoked the moon, while its mountaintop habitat drew associations with the lofty heavens.

This connection is vividly seen in the constellation Capricorn—a hybrid goat-fish figure tied to both stars and rain. Similarly, on ancient Iranian pottery from Tall-i-Bakun, Tape Hissar, and Susa, ibexes appear beside suns, stars, crosses, and circular points, suggesting that they were seen as mediators between earth and sky.

As the study notes, “As the ibex lives in the mountains naturally, ancient societies believed that this animal is closely related to the sky and stars.” In a world where natural cycles and cosmic rhythms guided agriculture, the ibex became both a symbol of life on earth and a signpost to the heavens.

A Symbol That Endured

The ibex endured as a powerful motif across the ancient Near East not only because of its practical value but because of its layered symbolic meaning. It represented sustenance—milk, meat, and wool—but also fertility, femininity, seasonal renewal, and the celestial order. Its persistence from Paleolithic cave paintings to Bronze Age artifacts demonstrates a remarkable continuity of human thought, carried through time in images and myths.

As Dr. Torkamandi and his colleagues conclude, the ibex is “deeply rooted in the human collective unconscious mind from the Paleolithic period to the present.” Across cultures, people looked at this mountain goat and saw not just an animal, but a messenger: of fertility, of rain, of stars, and of the eternal cycles that bind humanity to nature.

Conclusion: The Eternal Goat

Today, when we look at the ibex scaling impossible cliffs, we may simply admire its agility and strength. But for ancient peoples, it was far more than that. It was a reminder of fertility’s mystery, of rain’s blessing, of the eternal link between earth and sky. In its horns, they saw crescents of the moon; in its mating season, the promise of crops; in its mountain home, the pathway to the stars.

The study in L’Anthropologie does more than decode the ibex’s symbolism—it shows us how humans have always searched for meaning in the natural world, weaving the behaviors of animals into the fabric of myth, religion, and cosmic understanding. The ibex, climbing between earth and heaven, remains one of the most enduring and enchanting of these symbols.

More information: Shirin Torkamandi et al, Analyzing the symbolic meaning of bovidae in prehistoric cultures, particularly emphasizing ibex motifs in ancient Iranian arts, L’Anthropologie (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.anthro.2025.103384