Along the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, nestled between the rugged mountains of Lebanon and the restless sea, there once flourished a people who would change the course of human history—not through massive armies or sprawling empires, but through sails, ships, and the ceaseless call of the horizon. These were the Phoenicians, a civilization that thrived between roughly 1500 BCE and 300 BCE. Though they never commanded vast land territories like the Egyptians, Assyrians, or Persians, the Phoenicians shaped the ancient world in subtler but enduring ways.

Masters of navigation, trade, and craftsmanship, the Phoenicians turned the Mediterranean into their highway, establishing colonies, spreading goods, and, most importantly, sharing ideas. They were storytellers without parchment, teachers without classrooms, and conquerors without swords. Their true empire was the sea, and their legacy is etched not in monuments of stone but in the cultural and intellectual foundations of Western civilization.

The Land That Shaped a Maritime People

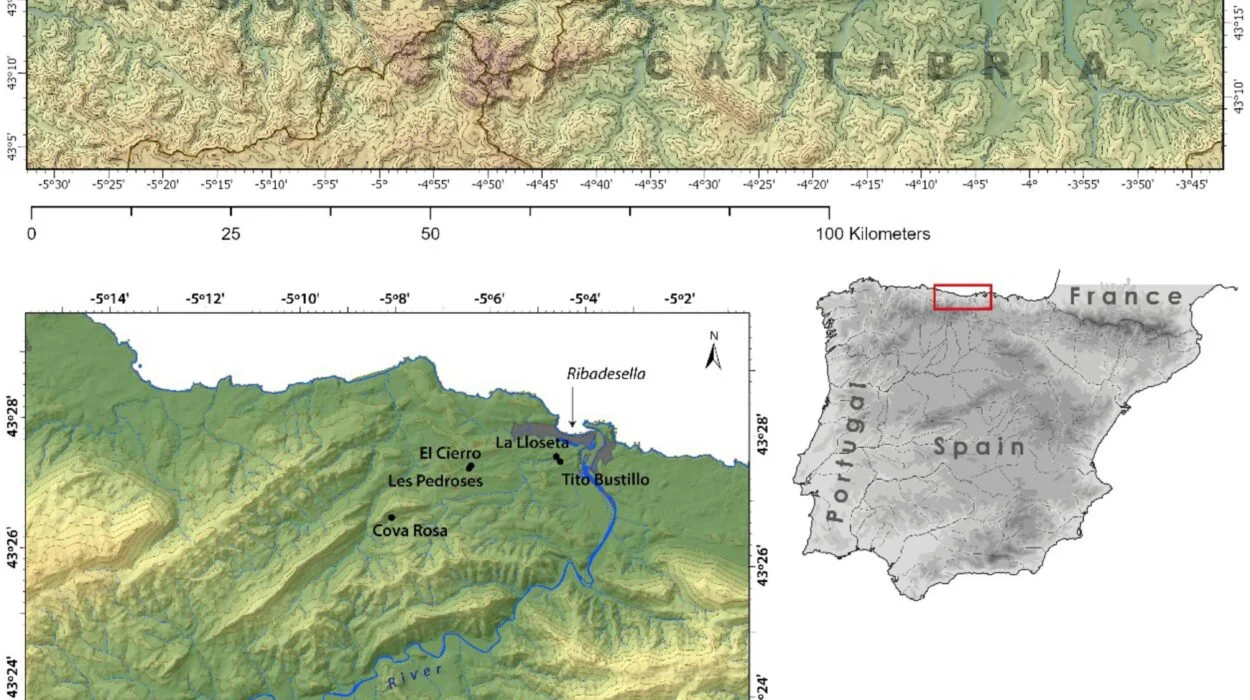

The geography of Phoenicia was destiny. Stretching along a narrow coastal strip where modern-day Lebanon, northern Israel, and parts of Syria lie, their homeland was hemmed in by mountains to the east and the Mediterranean to the west. With little fertile land for agriculture compared to Egypt’s Nile Valley or Mesopotamia’s river plains, the Phoenicians turned outward.

The sea became both livelihood and lifeline. Cedar forests, abundant in the Lebanese mountains, provided timber for shipbuilding, fueling an industry that would carry Phoenician influence across three continents. Natural harbors like Tyre and Sidon gave rise to thriving port cities. Geography, often a cruel master in history, was instead a gift that nudged the Phoenicians toward innovation and daring.

The Great Cities of Phoenicia

The heart of Phoenician civilization lay in its city-states, each independent yet bound by shared culture and language. Sidon, Tyre, Byblos, Arwad—names that echo across ancient texts—were not just cities but hubs of commerce, craftsmanship, and diplomacy.

Byblos, among the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, became renowned for exporting papyrus to Egypt and beyond, so much so that the Greek word for book (biblion) derives from its name. Sidon earned fame for its glassmaking, producing delicate vessels prized throughout the Mediterranean. Tyre, perched on an island off the coast, grew into a formidable maritime power, giving birth to colonies as far west as Spain.

These cities were fiercely independent, often competing with one another, but together they projected Phoenician culture outward. Unlike empires that sought to dominate through force, the Phoenician city-states thrived by weaving themselves into the economic and cultural fabric of their neighbors.

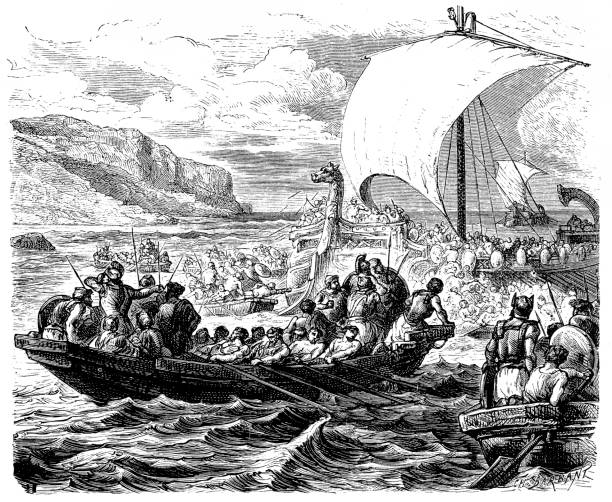

Masters of the Mediterranean

The Phoenicians are remembered above all as seafarers. Their ships, sleek and sturdy, carried them farther than most civilizations of their time dared to dream. They were not merely traders—they were explorers who mapped coastlines, established colonies, and pushed the limits of navigation.

By the first millennium BCE, Phoenician ships crisscrossed the Mediterranean. They carried cedar wood, glass, textiles dyed with the rare purple pigment extracted from murex snails, and precious metals. In return, they brought back grain from Egypt, silver from Spain, and tin from distant lands—essential for making bronze. Their trade routes formed a vast network, linking cultures from Mesopotamia to the Atlantic Ocean.

Colonization was central to their maritime strategy. The most famous Phoenician colony was Carthage, founded in present-day Tunisia around 814 BCE. Carthage would later grow into a powerful empire that rivaled Rome itself, but it began as a Phoenician outpost, one of many that dotted the Mediterranean coastlines in Cyprus, Sardinia, Sicily, and Spain.

The Phoenicians’ seafaring prowess also gave rise to legends. Herodotus, the Greek historian, claimed that Phoenician sailors undertook a circumnavigation of Africa under Egyptian commission around 600 BCE—a feat that, if true, demonstrates their extraordinary navigational skills centuries before Europeans attempted the same.

The Purple People

One of the Phoenicians’ most distinctive contributions was their mastery of dye production. From the murex snail, a small sea mollusk, they extracted a pigment that produced a brilliant, long-lasting purple. This color became synonymous with royalty and prestige, so much so that the word “Phoenician” itself is believed to come from the Greek phoinix, meaning both “purple-red” and “Phoenician.”

The process was labor-intensive and costly, requiring thousands of snails for a single garment. But the result was a dye so vibrant and durable that it symbolized wealth and power across the ancient world. Kings, emperors, and high priests draped themselves in “Tyrian purple,” turning a humble sea snail into a cornerstone of Phoenician economic power and cultural identity.

Innovators of Writing

While the Egyptians gave us hieroglyphs and the Mesopotamians developed cuneiform, both systems were complex and difficult to master. The Phoenicians, with their mercantile spirit, required something simpler, faster, and more adaptable—a script suited for trade across diverse cultures.

Around the 11th century BCE, the Phoenicians introduced an alphabet consisting of just 22 characters, each representing a consonant sound. This alphabet was revolutionary in its simplicity and portability. Merchants could use it to record transactions, scribes could teach it with ease, and foreign cultures could adopt and adapt it.

The Phoenician alphabet spread like their ships, carried to Greece, where it was modified with vowels to form the Greek alphabet, and later to Rome, evolving into the Latin alphabet that underpins much of modern Western writing. Every time we write a word today, we echo a Phoenician innovation, their script whispering across millennia.

Religion and Mythology

Like many ancient peoples, the Phoenicians practiced a polytheistic religion, deeply entwined with nature and the sea. Each city had its patron deity: Baal was a storm god often associated with fertility and kingship; Astarte (or Ishtar) embodied love and war; Melqart, the chief god of Tyre, symbolized strength and renewal, later identified with the Greek Heracles.

Religious practices included offerings, temples, and, controversially, rites that ancient sources claim involved child sacrifice—though scholars debate the accuracy and extent of these accounts. What is clear is that Phoenician religion was not confined to their homeland; it traveled with them, influencing the pantheons of neighboring cultures. Carthage, for instance, preserved and expanded Phoenician religious traditions long after Tyre had declined.

Between Empires: Survival Through Diplomacy

The Phoenicians lived in a dangerous neighborhood. Their small city-states lay between powerful empires—Egypt to the south, Mesopotamian powers to the east, and later, the Assyrians, Babylonians, and Persians. With little land or military strength to resist, the Phoenicians survived through diplomacy, tribute, and strategic alliances.

They often submitted to imperial overlords, paying taxes in exchange for autonomy, while continuing to thrive through trade. Their ships became invaluable to empires seeking naval strength. When the Persians rose to power, Phoenician fleets played a critical role in their campaigns, including the attempted invasion of Greece in the 5th century BCE.

This pragmatic flexibility ensured their survival, but it also meant that Phoenician political independence was fragile. By the time of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE, Phoenician cities were brought under Macedonian control. Tyre famously resisted Alexander in a seven-month siege, but even its defiance ended in conquest.

Carthage: The Last Flame of Phoenicia

Although the Phoenician homeland eventually fell under foreign rule, their colonies carried forward their legacy. Carthage, in particular, grew into a superpower. Rising on the North African coast, it expanded Phoenician influence westward, establishing its own empire and dominating trade in the western Mediterranean.

For centuries, Carthage flourished as a maritime giant, inheriting the Phoenician mastery of seafaring. But its clash with Rome in the Punic Wars sealed its fate. By 146 BCE, Carthage was destroyed, marking the symbolic end of Phoenician independence. Yet even in its fall, the memory of the Phoenicians endured, embedded in the cultural DNA of the Mediterranean world.

The Phoenicians’ Enduring Legacy

Though their cities crumbled and their independence was lost, the Phoenicians left behind legacies that continue to shape our world.

They gave us the alphabet—the very foundation of written communication for much of humanity. They pioneered global trade networks, setting the stage for later maritime empires. They spread technologies, ideas, and artistic influences across continents. They demonstrated the power of soft influence—commerce, culture, and innovation—over brute force.

Even their association with the color purple lives on. To this day, purple remains a color linked with royalty, wealth, and prestige, a reminder of the Phoenician genius for turning nature’s resources into enduring symbols of power.

Conclusion: A Civilization Without Borders

The Phoenicians remind us that history is not only written by conquerors. Sometimes, it is carried by traders, sailors, and artisans who build bridges rather than walls. Their story is one of resilience, innovation, and connection—a people who thrived not by dominating land but by mastering the sea.

In the restless waves of the Mediterranean, the Phoenicians found both challenge and opportunity. Their sails caught the winds of history, and their legacy still ripples across time. Every book we open, every letter we write, every time we admire the ocean’s vastness, we walk in the wake of these ancient mariners.

The Phoenicians may not have left behind pyramids or vast empires, but they left us something more enduring: a vision of humanity as interconnected, restless, and endlessly curious. They were, and remain, the master seafarers of the ancient world.