In 1960, deep within the limestone chambers of Petralona Cave in northern Greece, a local villager stumbled upon a discovery that would baffle scientists for decades: a nearly complete human cranium, cemented into the rock by thick mineral deposits. The skull, neither fully Neanderthal nor fully modern human, quickly became one of the most mysterious fossils in Europe.

For more than half a century, the “Petralona skull” has puzzled researchers, not only because of its unusual features but also because no one could agree on exactly how old it was. Previous estimates ranged wildly—from as “young” as 170,000 years to as “ancient” as 700,000 years. Each new analysis added more intrigue to the story, leaving the fossil suspended between competing timelines of human history.

Now, new research led by the Institut de Paléontologie Humaine is finally providing fresh clarity. Using advanced uranium-series dating techniques, scientists have been able to pin down a more precise minimum age, helping to position the Petralona skull within the complex mosaic of human evolution.

A Face from a Forgotten Lineage

When scientists first examined the Petralona cranium, they realized it did not fit neatly into the categories of known hominins. Its brow ridges were heavy and pronounced, its face broad, and its braincase intermediate in size—larger than that of early Homo species but not as rounded as Homo sapiens. It was distinctly human, but not like us.

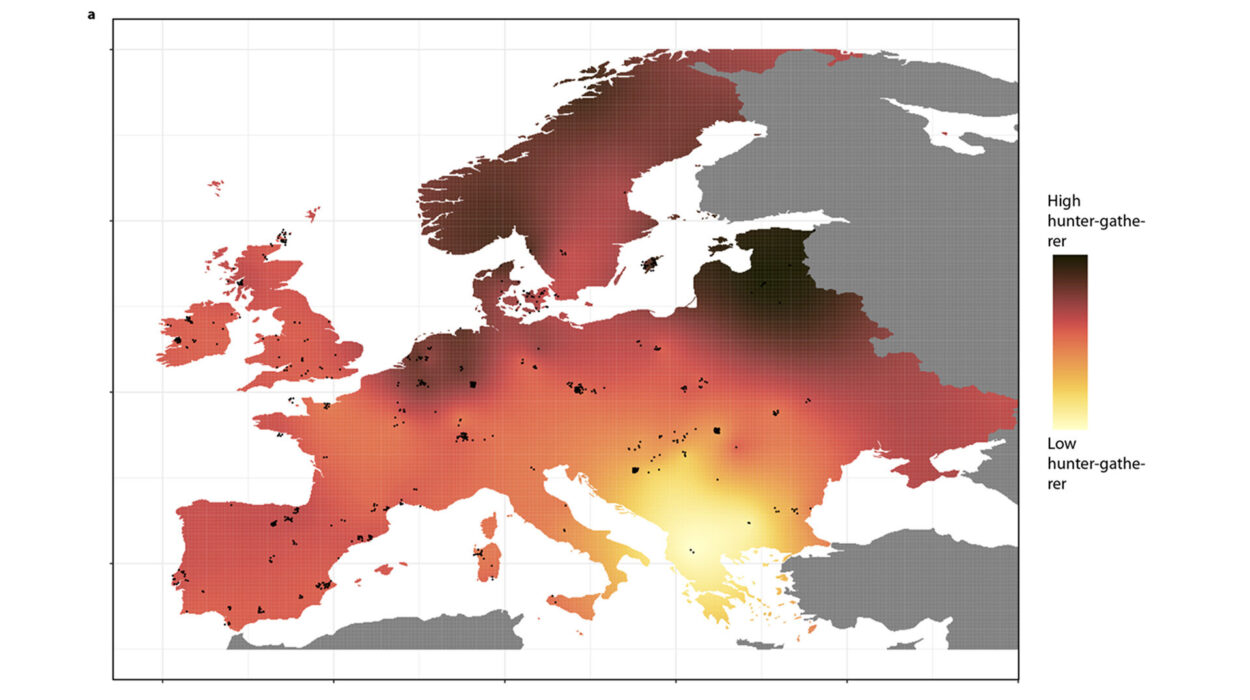

This peculiar mix of traits suggested it belonged to a lineage separate from both modern humans and Neanderthals. If true, it meant that during the Middle Pleistocene, Europe may have been home to more than one kind of human—parallel populations living, adapting, and perhaps even competing in the same landscapes.

For decades, the skull stood as a silent witness to a hidden chapter of human evolution, waiting for technology advanced enough to unlock its story.

Dating the Undatable

The greatest obstacle in solving the Petralona puzzle was time. Without an accurate age, the fossil could not be placed within the evolutionary tree. Early dating attempts were inconsistent because the skull was encased in thick calcite deposits—mineral crusts formed by dripping cave water over thousands of years. These crusts made traditional dating methods unreliable.

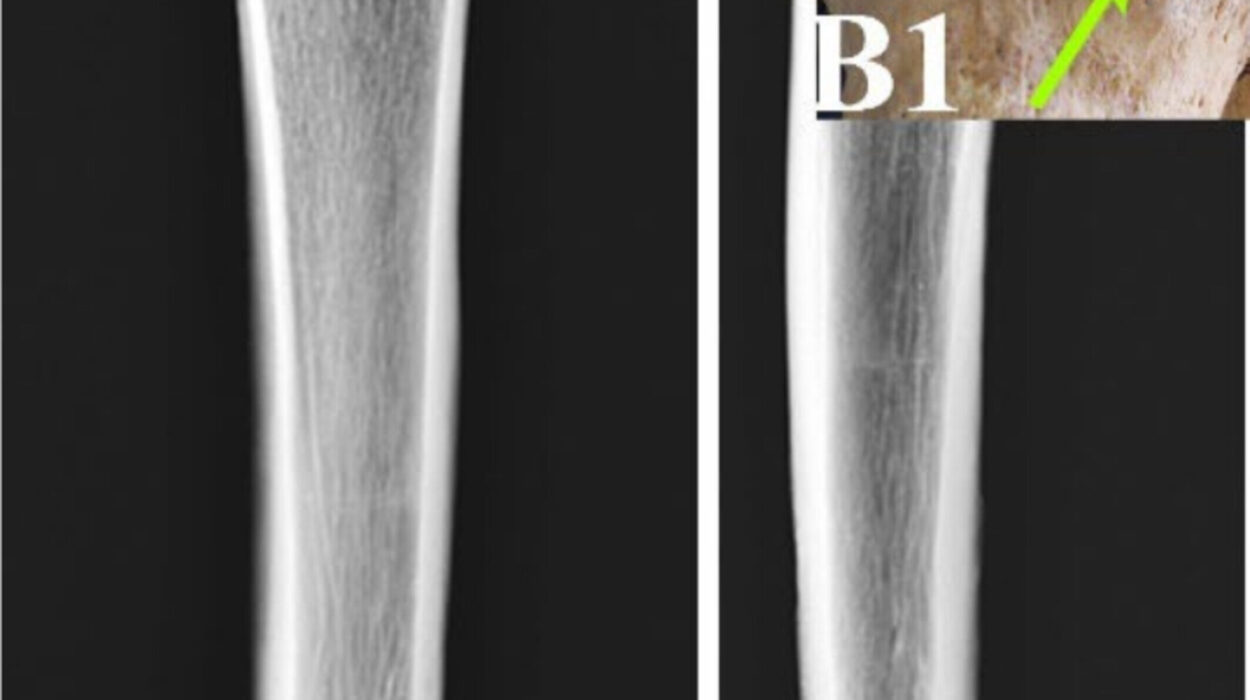

That is where uranium-series (U-series) dating comes in. This technique takes advantage of a natural process: when water seeps through soil and cave walls, it carries with it trace amounts of uranium. Over time, uranium isotopes decay into thorium at a fixed, predictable rate. By measuring the ratio of uranium to thorium in the calcite layers covering the fossil, scientists can determine when those deposits first began to form.

Unlike dating soil, where uranium is constantly replenished and resets the “clock,” cave deposits create a closed system once they harden. This makes U-series dating a powerful tool for establishing minimum ages of fossils sealed within mineral coatings.

What the New Study Reveals

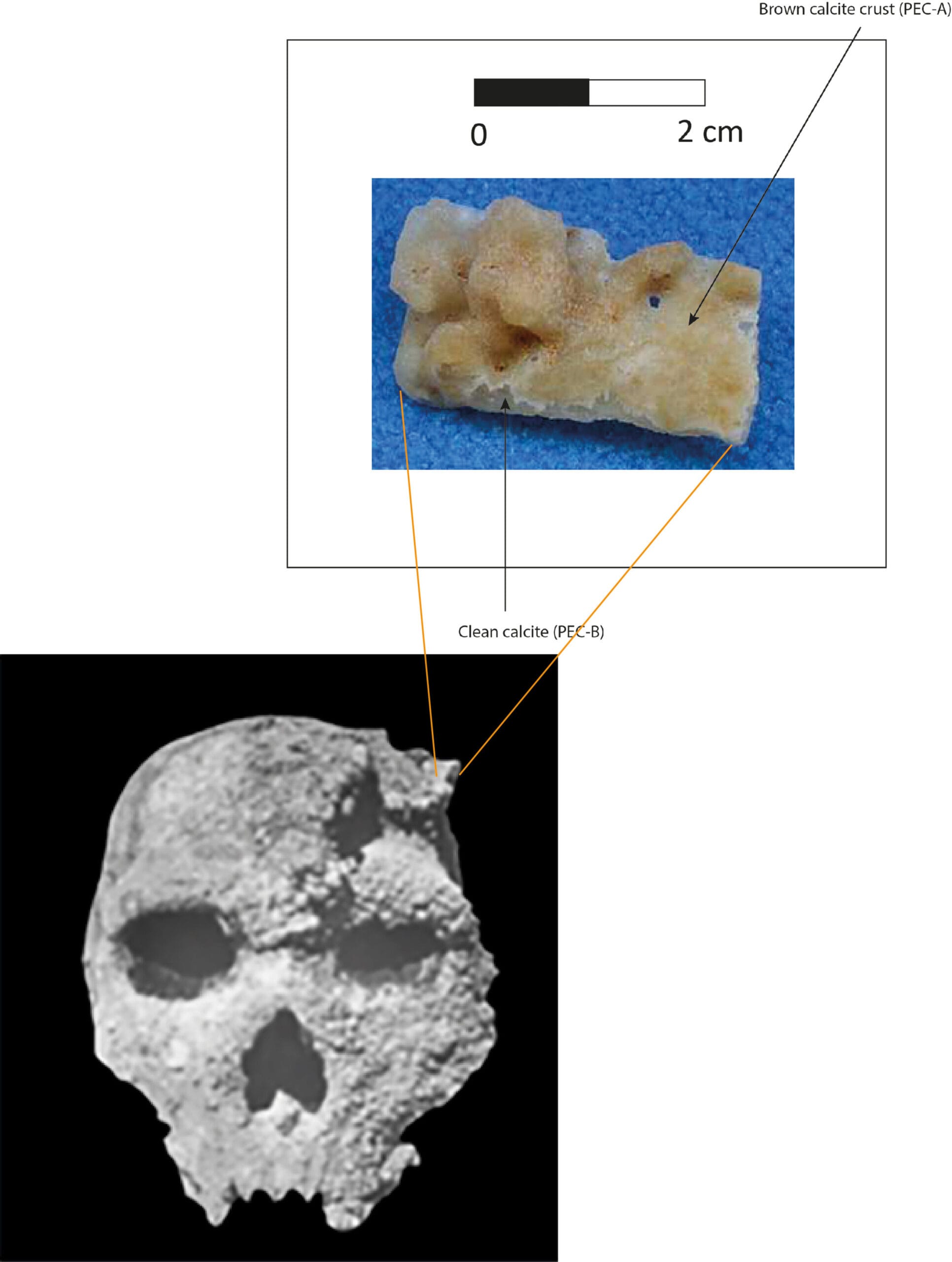

In the new study, researchers sampled calcite directly from the skull’s surface, as well as from other mineral formations in the cave. The results were striking. The crust covering the cranium revealed a minimum age of 286,000 ± 9,000 years. This means the skull must be at least that old—and possibly much older if it remained dry before calcite began to form.

Other cave formations provided additional context. Stalagmites in the chamber where the skull was found were dated to between 510,000 and over 650,000 years old, proving that the cave environment itself was well established long before the cranium was deposited. Stratigraphic evidence suggested that the skull likely dates somewhere between 539,000 and 277,000 years ago, placing it firmly in the Middle Pleistocene.

This timeline is crucial. It means the Petralona individual lived at a time when multiple human populations were spreading across Europe, some evolving toward Neanderthals, while others—like the Petralona lineage—may have followed a different evolutionary path.

A Primitive Cousin, Not Quite Neanderthal

The study concludes that the Petralona hominin represents a more primitive branch of humanity, distinct from both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. Its features suggest it belonged to an older European population that coexisted alongside early Neanderthals during the later Middle Pleistocene.

This supports a picture of human evolution not as a simple linear progression, but as a branching tree with multiple populations overlapping in time and space. Far from being alone, our species and our close relatives shared the continent with other hominins—each adapting to the challenges of Ice Age Europe in their own way.

Why It Matters

The Petralona skull is not just a fossil; it is a messenger from a forgotten time. Its presence tells us that human evolution in Europe was far more complex than once believed. Instead of a neat sequence from early Homo to Neanderthals and then to modern humans, the reality was messy, filled with parallel lineages, evolutionary experiments, and perhaps even interbreeding events.

For decades, the Petralona skull was a riddle wrapped in stone. Now, with more precise dating, we are beginning to place it on the evolutionary map. Yet questions remain: Who exactly were the Petralona people? Did they interact with early Neanderthals? Did their lineage vanish, or do traces of them still echo in our DNA today?

The Skull That Refuses to Be Forgotten

The cranium from Petralona Cave continues to spark debate, fascination, and even controversy among scientists. Every new piece of evidence adds another layer to the story of human origins. What is clear, however, is that this skull—discovered by chance, cemented in stone for hundreds of thousands of years—has become one of the most important fossils for understanding Europe’s deep past.

As technology improves, and as researchers continue to revisit old finds with new tools, the Petralona skull may yet yield more secrets. For now, it stands as a haunting reminder of the diversity of human history—an ancient face peering out from the shadows of time, urging us to remember that we were never alone in our evolutionary journey.

More information: Christophe Falguères et al, New U-series dates on the Petralona cranium, a key fossil in European human evolution, Journal of Human Evolution (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2025.103732