Buried in a ceramic pot carved into the warm hillside of ancient Egypt, one man’s bones lay undisturbed for nearly five millennia—his silent presence outliving kingdoms, languages, and even empires. He lived during the dawn of the Old Kingdom, when the first monumental pyramids were rising from the desert sands. And now, thanks to a breakthrough in genetic science, his story is being told—not in hieroglyphs, but in the language of DNA.

Researchers from the Francis Crick Institute and Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) have sequenced the oldest known Egyptian genome, from a man who lived between 4,500 and 4,800 years ago. Their findings, published in the journal Nature, mark a historic first: the successful decoding of an entire ancient Egyptian genome, offering direct genetic evidence of early population mixing between North Africa and the Fertile Crescent, the cradle of civilization in West Asia.

A Long Journey from Tomb to Test Tube

The individual whose DNA has now become a window into the past was unearthed in 1902, in the village of Nuwayrat, around 265 kilometers south of Cairo. He had been buried in a time before artificial mummification was commonplace—laid to rest inside a ceramic vessel, his grave carved into the hillside.

The body was excavated under British rule by a committee organized by archaeologist John Garstang and later donated to the World Museum Liverpool, where it survived even the bombs of the Blitz during World War II.

More than a century after his excavation, the man’s story took a dramatic turn. Researchers successfully extracted genetic material from his tooth—an achievement that defies decades of failed attempts. Egypt’s scorching climate has long posed a severe challenge to ancient DNA preservation, thwarting even the Nobel Prize-winning efforts of Svante Pääbo in the 1980s. But new technology has finally broken through.

“This individual has been on an extraordinary journey,” said Linus Girdland Flink, co-senior author and Lecturer in Ancient Biomolecules at the University of Aberdeen. “He lived and died during a critical period of change in ancient Egypt. We’ve now been able to tell part of his story.”

Genetic Bridges Between Continents

Analysis of the man’s genome revealed that 80% of his ancestry traced back to ancient North Africans—expected for someone who grew up in Egypt. But the other 20% told a more surprising tale, pointing to genetic links with populations in Mesopotamia, in what is today Iraq and parts of Iran and Jordan.

This blend offers the first genetic confirmation of what archaeologists had long suspected from pottery, trade goods, and writing systems: that ancient Egypt was not an isolated civilization, but part of a wider web of cultural and biological exchange that stretched across continents.

“Ancient Egypt is a place of extraordinary written history and archaeology,” said Pontus Skoglund, Group Leader of the Ancient Genomics Laboratory at the Crick. “But challenging DNA preservation has meant that no genomic record of ancestry in early Egypt has been available—until now.”

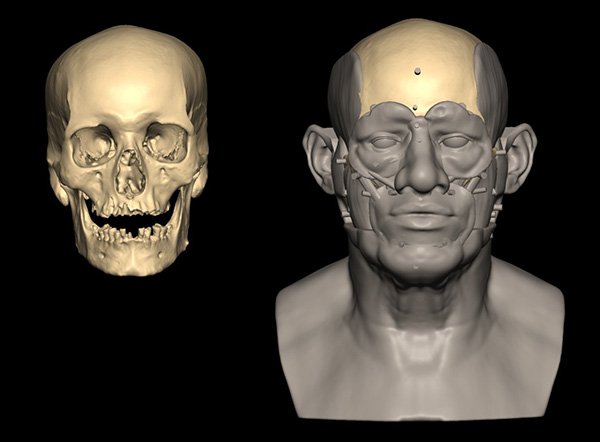

The Life Behind the Bones

This man was not merely a genetic puzzle. His bones told a story of daily life, labor, and even social status.

By examining his teeth and bones, researchers estimated that he was an adult male, likely in his 30s or 40s, who had grown up locally. The chemical signals in his enamel—tiny traces of his diet and environment—pointed to an Egyptian upbringing, suggesting that even if his ancestors migrated from West Asia, he himself had lived entirely within the Nile Valley.

His skeleton held other secrets. His seat bones were unusually expanded, his arms bore marks of repetitive forward movement, and his right foot showed signs of severe arthritis. These clues, combined, point toward a life of repetitive labor, likely as a potter—a profession demanding long hours in seated positions with precise arm motions.

Intriguingly, he was buried with what appears to be unusually high status for a tradesman. Potters were typically not given such elaborate burials. Could he have been a master craftsman, someone whose skill or innovation elevated him in society? Perhaps he was among the first to use the potter’s wheel, introduced to Egypt during this very era.

“The markings on the skeleton are clues to the individual’s life and lifestyle,” said Professor Joel Irish, co-author and anthropologist at LJMU. “He may have been exceptionally skilled—or socially mobile in a way we rarely associate with ancient laborers.”

From Ancient Tooth to Genetic Revelation

To extract DNA from such ancient material, researchers had to overcome enormous technical barriers. Warm climates degrade DNA rapidly, fragmenting genetic material into nearly unreadable strands. But recent innovations in ancient genomics allowed scientists to isolate and authenticate even these degraded fragments, while also ruling out contamination from modern human DNA—a common obstacle in ancient studies.

The result is not just a single genome—it’s a proof of concept that Egyptian DNA, long considered a scientific dead end, can in fact be retrieved and studied with today’s tools.

“We’re now able to cross these technical boundaries,” said Skoglund. “This is a leap forward in ancient genomics—and a huge step in understanding how ancient Egyptian society was shaped by contact with the broader ancient world.”

The Beginning of a Genetic Map

For the research team, this is just the start.

“We hope that future DNA samples from ancient Egypt can expand on when precisely this movement from West Asia started,” said Adeline Morez Jacobs, first author and visiting fellow at LJMU. “Piecing together all the clues from this individual’s DNA, bones, and teeth has allowed us to build a comprehensive picture.”

Already, the study challenges earlier assumptions and opens new doors in the field of human ancestry, migration, and early globalization.

But the researchers stress that a full understanding of Egypt’s population history will require many more sequenced genomes, drawn from different regions, time periods, and social classes. Only then can we begin to trace the complex tapestry of Egyptian identity across thousands of years.

A Story Told Without Words

This man left no name, no monument, and no inscription. But through bone, enamel, and genome, he speaks to us across the ages. His DNA tells a story of movement, mingling, and memory. His skeleton, scarred by labor, hints at a life of craftsmanship. And his grave, sealed in silence for nearly five millennia, now echoes with the voices of science.

He reminds us that ancient Egypt, for all its grandeur and mystery, was also profoundly human—a place where individuals lived, worked, traveled, and died, leaving behind traces that science is only now beginning to decode.

And in that decoding, we don’t just discover the past—we connect with it.

Reference: Morez Jacobs, A. et al. Whole-genome ancestry of an Old Kingdom Egyptian. Nature. (2025) DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09195-5. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09195-5