In the desolate grasslands of northeastern Mongolia, where the wind hums across the ancient steppe and the horizon feels as wide as time itself, a silent voice is rising from the dirt—one carried not in royal edicts or elegant scrolls, but in the bones of sheep, horses, and gazelles.

These bones, forgotten in a trash heap nearly a thousand years old, are now rewriting what we know about life on the fringes of one of medieval Asia’s most enigmatic empires. And they’re telling a story we’ve rarely heard: not one of emperors or conquest, but of survival, hardship, and resilience.

A Frontier Unlike the Textbooks

The Liao Empire (916–1125 CE), ruled by the semi-nomadic Khitan people, once stretched across the vast expanses of what is now northern China and Mongolia. Its rulers left behind ornate tombs, imperial chronicles, and lavish court records. But as is often the case in history, the voices of those who lived outside the palace walls—those who guarded its boundaries and endured its winters—were all but erased.

Until now.

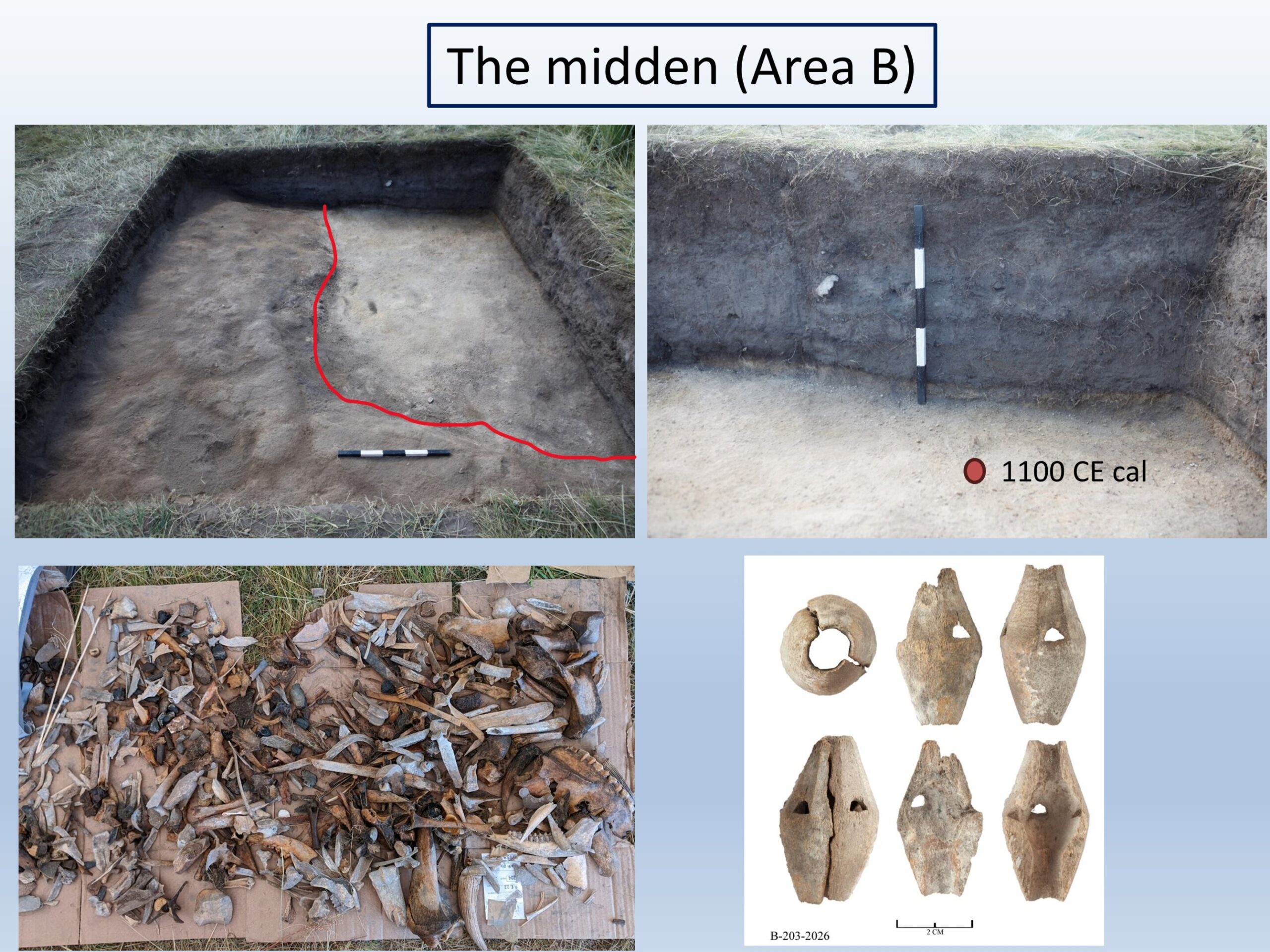

At a lonely garrison site known as “Site 23,” nestled along the 4,000-kilometer-long wall system that once marked the Liao Empire’s northern frontier, archaeologists have discovered a treasure trove of animal bones—more than 7,000 in all. They weren’t buried with reverence or stored in royal archives. They were discarded, left behind in a midden—a trash pile.

But what a trash pile can reveal is sometimes more intimate, more human, than any gilded manuscript.

“This wasn’t just a checkpoint manned by troops waiting for orders,” says Tikvah Steiner, a doctoral researcher at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and lead author of the study published in Archaeological Research in Asia. “This was a living, breathing outpost where people raised animals, hunted, fished, and faced the raw edge of the environment—probably with little help from the empire they served.”

Life Among the Bones

The excavation is part of a larger project called “The Wall—people and ecology in medieval China and Mongolia,” led by Prof. Gideon Shelach-Lavi of Hebrew University’s Department of Asian Studies. What the team uncovered at Site 23 is a snapshot of daily life in the margins of empire, frozen in time around 1050 CE.

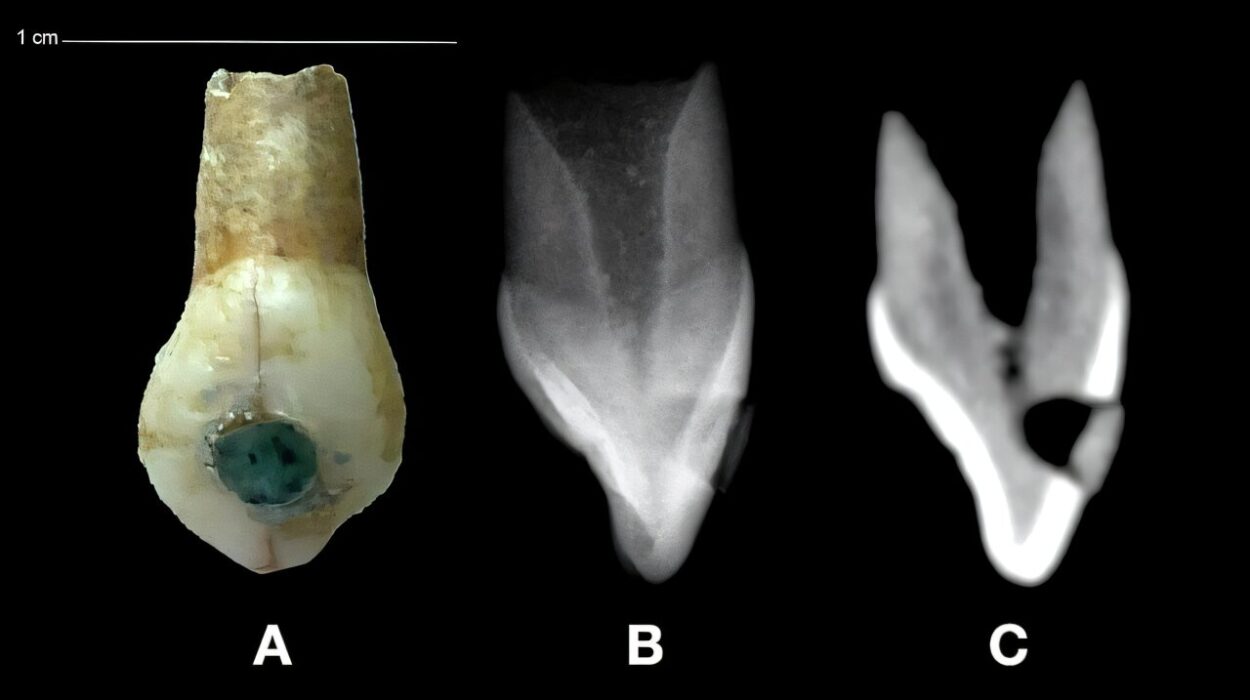

Among the bones, researchers identified sheep, goats, horses, dogs, gazelles, and even catfish. Some were butchered with care. Others bore the telltale signs of emergency: marrow bones cracked open, neonatal animals lost too soon, and skeletal remains burnt, split, or carved into tools and ornaments.

One remarkable find was a whistling arrowhead—delicately carved from bone—a haunting relic of the martial culture that once echoed across these high plains. But most of the evidence points not to war, but to quiet persistence. People here were herders, hunters, fishers. They were caretakers of their own survival.

“The presence of so many newborn animal bones, especially from lambs and puppies, suggests that this community may have endured a harsh climatic event,” explains Steiner. “Possibly a late freeze that killed young animals before they could survive the spring.”

That one detail alone—the scattered remains of fragile newborns—paints a picture of a community enduring both environmental hardship and political neglect. Far from the grandeur of imperial chronicles, these people were living on the edge—in every sense.

Beyond the Palace Walls

The Liao dynasty’s own records, preserved in texts like the Liaoshi, are rich with descriptions of court rituals, diplomatic missions, and royal hunts. But they are nearly silent on the everyday lives of soldiers, farmers, and families living in distant outposts like Site 23.

This absence isn’t surprising. Most imperial histories focus on elite narratives: kings, generals, wars. But archaeology has the power to reveal another kind of truth—one that seeps through the soil and survives where paper fails.

“These bones are voices,” says Prof. Rivka Rabinovich, co-author of the study. “They’re a form of testimony. They tell us who was there, what they ate, how they lived. It’s not a story of conquest—it’s a story of endurance.”

And perhaps that’s the story modern readers need now more than ever.

A New Lens on Empire

The implications of this research stretch far beyond Mongolia. Site 23 is not just a garrison; it’s a case study in how frontier communities adapt imperial policy to local reality. This population, whether made up of soldiers, civilians, or both, wasn’t passively receiving orders from the center—they were making choices, building a life, and improvising survival strategies in a remote and unforgiving environment.

“We see signs of self-sufficiency,” Steiner explains. “They were breeding animals, making tools, supplementing their diet through hunting and seasonal fishing. There’s even evidence they selected which animals to slaughter and which to keep based on local needs—not just imperial supply lines.”

In other words, the wall was more than a boundary. It was a living landscape—home to real people who weren’t merely guarding the empire’s edge, but shaping it.

The study also contributes to a broader comparative understanding of life on imperial frontiers, from the Roman limes in Europe to the fortresses along the Great Wall of China. How do empires manage their edges? And what happens when the people on the margins start writing their own stories—if not in ink, then in bone?

A Trash Heap’s Legacy

What may seem like a mundane archaeological deposit—a pile of old bones—turns out to be a rare and moving archive. It documents not only how people lived, but how they endured. It tells of cold nights, lost lambs, simple meals, and quiet moments spent fashioning bone tools by firelight.

These aren’t the kinds of details that empires preserve. But they’re the ones that make history human.

As researchers continue to investigate other sites along the medieval wall system, the hope is that more such stories will come to light—stories that show us not just how empires rose and fell, but how ordinary people found ways to live, love, adapt, and persist.

“We can’t always hear the voices of the past,” says Rabinovich. “But sometimes, if we listen closely, the bones will speak.”

Reference: Tikvah Steiner et al, Subsistence and survival along the medieval long-wall system of northern China and Mongolia: A zooarchaeological and historical perspective, Archaeological Research in Asia (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.ara.2025.100639