In the rugged cliffs and hidden caves of Southwest China, an ancient burial tradition has captivated archaeologists and historians for centuries. The Hanging Coffins, eerie wooden tombs perched precariously on vertical rock faces, have long puzzled researchers. Who were the people who built these astonishing structures? And what happened to them over the course of history?

A new study has finally begun to answer these questions in an unexpected and fascinating way. By diving deep into the genetic heritage of both ancient and modern populations, researchers have uncovered a stunning link between the mysterious Hanging Coffin communities and the modern-day Bo people, who still inhabit regions of China today. What’s even more surprising is how the genetic connections between these ancient practices and today’s world reveal an intricate web of migration, cultural exchange, and survival.

The findings, published in Nature Communications, offer unprecedented insight into the ancestral roots of these enigmatic burial practices and the people associated with them. The study, led by Prof. Zhang Xiaoming from the Kunming Institute of Zoology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, provides an evocative glimpse into how genetic evidence can illuminate the past in ways that traditional archaeological methods alone cannot.

The Ancient Coffins and Their Forgotten People

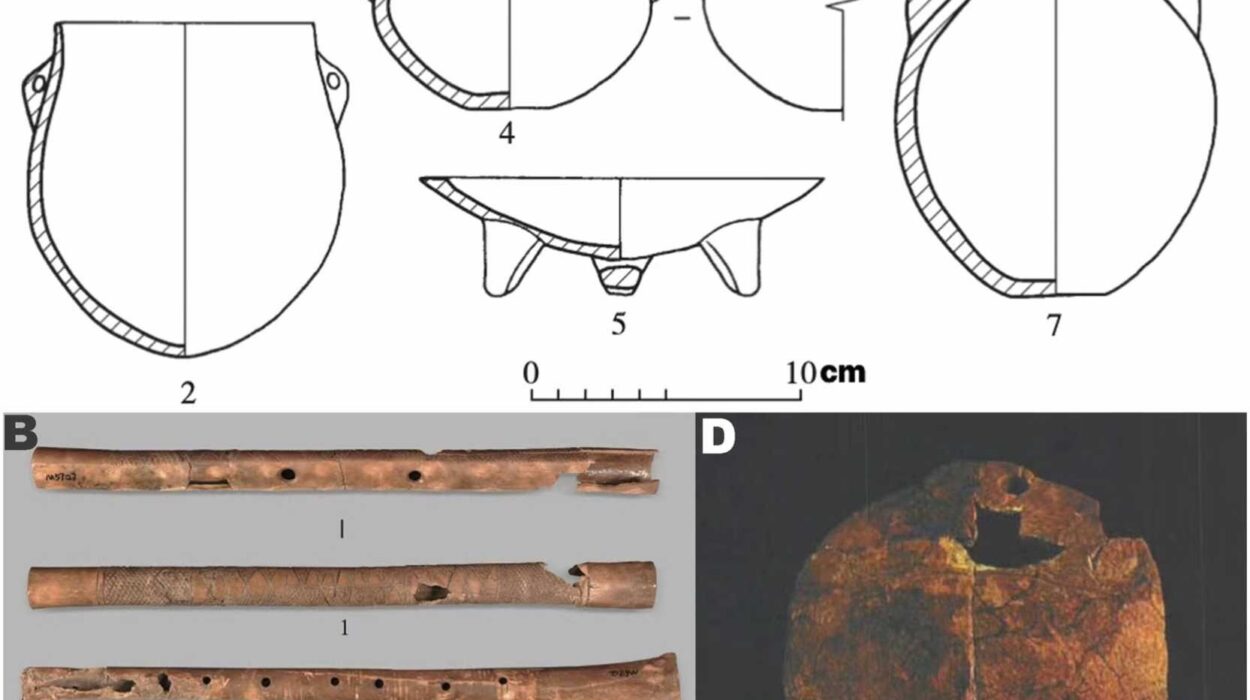

The Hanging Coffins have long been linked to the Bo ethnic group, an ancient population believed to have disappeared after the Ming Dynasty. These tombs, often found in remote regions, contain wooden coffins suspended on steep cliff faces or inside caves, creating a striking, otherworldly image. For years, this unique mortuary practice has been a subject of intrigue, and its origins remained shrouded in mystery.

The Bo people were once thought to be the architects behind these extraordinary burial sites. But who were they, really? And why did they choose such dramatic ways to honor their dead? While historical records about the Bo are scarce, there were tantalizing hints that the practices of the Hanging Coffins might extend further into the past than previously imagined. What’s more, the question remained: Did these ancient traditions survive in some form, or had they disappeared altogether?

This new study suggests that the Bo people’s genetic legacy has not disappeared but rather persists in the DNA of their modern-day descendants. By comparing the genomes of 11 ancient individuals from four Hanging Coffin sites in China, as well as ancient specimens from Log Coffin sites in Thailand, the researchers found something extraordinary. The Bo people, long thought to be a lost group, share significant genetic ties with these ancient populations.

Ancient DNA: A Clue to Migration and Interaction

Through an extensive genomic analysis, Prof. Zhang and his collaborators found that modern Bo individuals possess a surprising degree of genetic inheritance from the ancient Hanging Coffin communities. This revelation rewrites a part of history, suggesting that the Bo people are not simply descendants of a singular, isolated group, but rather carry within their genes the traces of ancient peoples who interacted and migrated across vast distances.

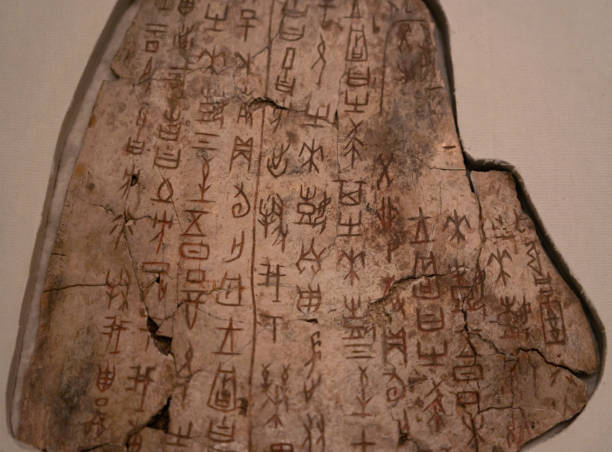

Even more intriguing, the study revealed that these ancient Hanging Coffin communities were not as culturally isolated as once believed. The genetic evidence connects these communities to southern East Asia’s coastal Neolithic populations, who are considered the ancestors of today’s Tai-Kadai and Austronesian language speakers. These groups, who spread out over Southeast Asia, played a pivotal role in shaping the genetic and linguistic diversity of the region.

However, the most unexpected finding came from the discovery of genetic diversity within the ancient Hanging Coffin population itself. Two individuals from the Wa Shi site in Yunnan, dating back approximately 1,200 years, exhibited strikingly different genetic profiles. One individual had genetic links to Yellow River agriculturalists and Tibetan-related populations, while the other showed connections to ancient Northeast Asian groups. This suggests that, during the Tang Dynasty, the Hanging Coffin people were involved in long-distance interactions, exchanging cultural and genetic material with groups far beyond their immediate environment.

Connections Across Borders

The study did not just focus on China. By including genetic data from populations in neighboring Thailand, the researchers found another surprising result. The genetic makeup of the Hanging Coffin people in China showed strong affinities with Log Coffin populations in Thailand, providing further evidence for a shared origin and a broader cultural network that spanned southern China and Southeast Asia.

Yet, it wasn’t a simple, uniform genetic picture. Instead, the researchers noted regional variations in ancestry. These differences point to the complex demographic processes at play in the region, including localized intermingling with Hoabinhian-related groups in Thailand. It is clear that ancient communities were not static, isolated entities, but rather part of a dynamic, interconnected world where populations mixed, traded, and migrated.

This discovery opens new doors for understanding the migrations and cultural exchanges that shaped the development of East and Southeast Asia. By linking genetic data with archaeological sites, scientists now have a more complete picture of the social and cultural networks that existed thousands of years ago. These networks, once thought to be fragmented or geographically confined, are revealed to have been far more interconnected than previously believed.

The Power of Genomic Evidence in Understanding Human History

What makes this study particularly groundbreaking is its use of genomic evidence to complement traditional archaeological findings. By comparing ancient DNA with contemporary genomes, the research team was able to fill in gaps in our understanding of human migration and cultural development. Genomic analysis, they argue, is an invaluable tool for tracing the flow of people, ideas, and cultural practices over time.

This integrative approach, which combines genetics, archaeology, and history, is paving the way for a more nuanced understanding of human evolution and migration. It shows how cultural traditions, like the Hanging Coffin practice, can survive not only in material remains like tombs and artifacts but also in the genes of living populations.

For marginalized communities whose histories have often been overlooked or misunderstood, this kind of research is particularly important. It underscores the resilience of cultural practices and the continuity of traditions that have shaped the identities of communities over millennia.

In this case, the Bo people, once thought to be a fading echo of the past, are revealed to be a living testament to an ancient, interconnected world. Their genes carry within them the traces of millennia of migration, cultural exchange, and survival—proof that the past is never as distant as we sometimes think.

Why This Research Matters

This study does more than uncover the ancient origins of a specific burial practice—it reshapes our understanding of human history itself. By revealing the genetic connections between the Bo people and the ancient communities that practiced the Hanging Coffin tradition, it demonstrates how genetic evidence can serve as a powerful tool for uncovering forgotten chapters of the past.

More broadly, this research highlights the complexity of human migration and the ways in which cultures, communities, and ideas have spread and evolved across time. It challenges the notion of isolated, static groups and emphasizes the interconnectedness of humanity. In doing so, it provides a deeper, richer understanding of the history of East and Southeast Asia and the lasting legacies of ancient peoples.

Ultimately, this study invites us to reconsider our place in the tapestry of human history and recognize that our modern identities are deeply woven into the stories of ancient civilizations—stories that continue to live on in our genes, our traditions, and the ways we connect with one another.

More information: Hui Zhou et al, Exploration of hanging coffin customs and the bo people in China through comparative genomics, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65264-3