When most people think of English history, two dates leap to mind: 1066, when William the Conqueror triumphed at Hastings, and 1215, when King John was forced to sign Magna Carta. But in truth, the story of England’s creation began much earlier—under a king whose name few today recognize.

Æthelstan, crowned in 925 AD, was the grandson of Alfred the Great and the man who first forged a united English kingdom. By 927 AD, through conquest, diplomacy, and sheer determination, Æthelstan had drawn together lands that had long been fractured by Viking invasions, rival rulers, and regional divisions. For the first time, an area that we would now call “England” existed under a single crown.

And yet, unlike his grandfather Alfred or later monarchs, Æthelstan has remained a shadowy figure in the public imagination. As Professor David Woodman of Cambridge University argues in his new biography The First King of England, this neglect is undeserved—and correcting it matters as England approaches the 1,100th anniversary of Æthelstan’s great achievement.

Why Has History Forgotten Him?

Part of the answer lies in timing. Alfred the Great had the good fortune to be immortalized by the Welsh monk Asser, who recorded his deeds in vivid detail. After Æthelstan’s death in 939, however, no court biographer stepped forward to capture his story. Worse still, within decades, later rulers and church reformers promoted their own champions—especially King Edgar, who reigned from 959 to 975—as the great architects of English unity and piety.

As Woodman observes, history is often shaped not only by what happened, but by who told the story. Æthelstan, lacking a storyteller, faded from the collective memory. Even in modern scholarship, some historians downplayed his importance by arguing that the kingdom fractured after his death. But, as Woodman insists, the fact that his creation did not endure flawlessly does not diminish the fact that he created England in the first place.

The Military King

If Alfred’s legacy was defense against the Vikings, Æthelstan’s was offense and expansion. His military power was formidable. In 927 AD, he captured the Viking stronghold of York, bringing Northumbria into his dominion. This victory marked the true beginning of England, a realm stretching from Cornwall in the southwest to the River Tweed in the north.

But conquest was only the beginning. Æthelstan demanded recognition from the rulers of Wales and Scotland, compelling them to attend his royal assemblies. Surviving records in the British Library show just how vast and theatrical these gatherings were, attended by nobles, bishops, and resentful kings pulled from their distant territories.

His greatest test came in 937 AD at the Battle of Brunanburh, when a grand coalition of Vikings, Scots, and Strathclyde Welsh sought to overthrow him. The clash was ferocious—chroniclers across the British Isles and Scandinavia recorded its bloodshed. Æthelstan’s victory was decisive, securing the survival of his fledgling kingdom.

“Brunanburh should be as famous as Hastings,” Woodman argues. And indeed, it was celebrated in Old English verse as a moment when England’s identity was forged in battle.

A Revolution in Government

Æthelstan’s genius, however, was not confined to the battlefield. He revolutionized the way kings ruled. Surviving law codes from his reign show a ruler deeply concerned with order, justice, and the responsibilities of kingship.

For the first time, royal documents became elaborate, almost theatrical statements of power. Written in elegant Latin and filled with rhetorical flourishes, these diplomas were not just legal instruments—they were propaganda, proclaiming a king who saw himself as chosen by God and destined to rule a united land.

More importantly, these documents reveal the beginnings of a centralized administration. Æthelstan deployed scribes to travel with him and ensure consistency in law and record-keeping. Reports flowed back to him from across the kingdom, offering early glimpses of a government that went beyond personal rule to something closer to a modern state.

At a time when much of continental Europe was splintering under feuding nobles, Æthelstan’s centralized authority was a remarkable innovation. He also strengthened England’s place in Europe by marrying his half-sisters into continental dynasties, weaving his house into the politics of the wider Christian world.

Champion of Learning and Religion

Though often remembered for war, Æthelstan was equally devoted to faith and scholarship. The Viking invasions had ravaged churches and monasteries, but under Æthelstan, learning flourished again. He invited scholars from across Europe to his court, supported scriptoria, and reestablished England as a center of Christian thought.

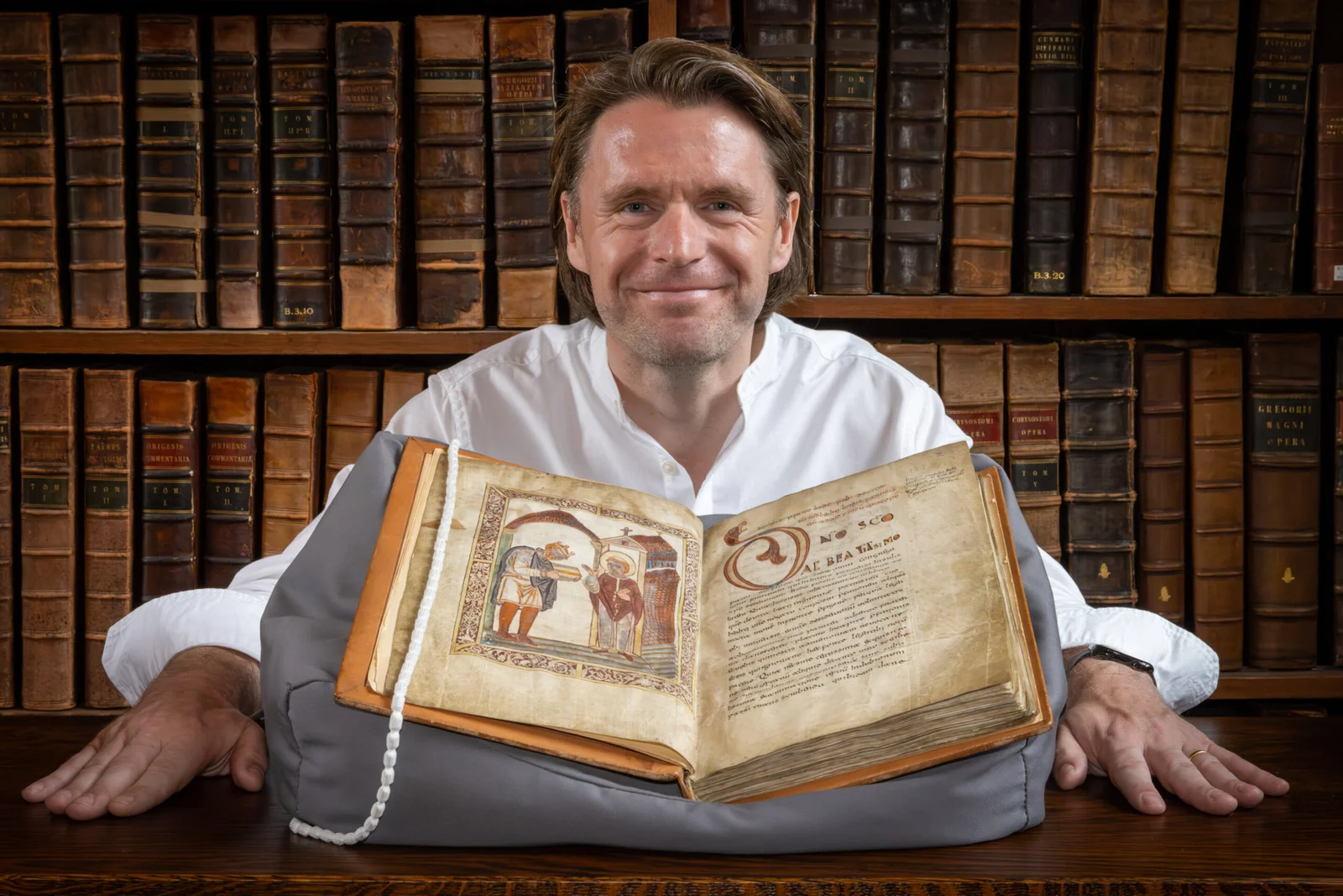

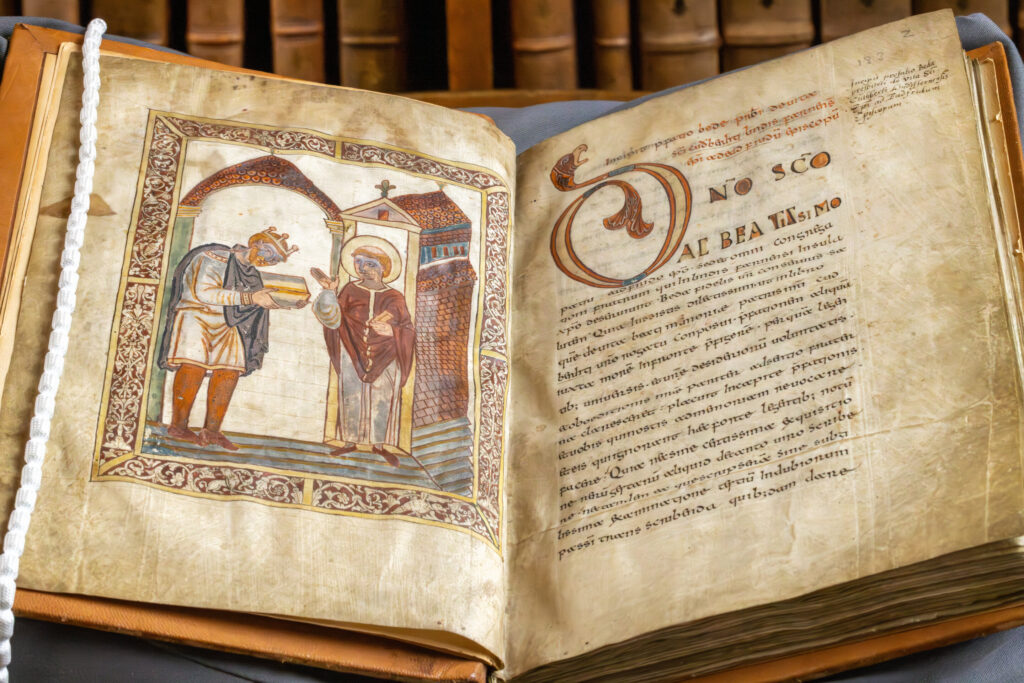

One extraordinary image survives of him: the earliest portrait of an English monarch, preserved in a manuscript now at Cambridge. In it, Æthelstan bows reverently before Saint Cuthbert, seeking legitimacy and blessing. The manuscript, likely a gift to Cuthbert’s community in newly-conquered Northumbria, was a masterstroke of diplomacy—binding religious authority to political conquest.

Another treasure, the Durham Liber Vitae, records the names of those tied to the saint’s community. At its top, in shimmering gold and silver ink, someone in Æthelstan’s entourage wrote “Æthelstan Rex.” To Professor Woodman, glimpsing this simple inscription was electrifying—it is as if the king himself still speaks from the tenth century, reminding us of his place in England’s story.

Why His Legacy Matters Today

As England marks 1,100 years since Æthelstan’s coronation in 925 and his unification of the realm in 927, Woodman and other historians are campaigning to secure him the recognition he deserves. Ideas include a statue, plaque, or portrait in a public place such as Westminster, Malmesbury (his burial site), or Eamont Bridge (where his authority was first acknowledged by other rulers).

Equally important is education. For too long, English schoolchildren have leapt from Alfred to Hastings, skipping over the moment of creation itself. To understand 1066, one must first understand 927. The story of conquest makes more sense when set against the story of foundation.

Æthelstan: England’s First King

Æthelstan’s reign lasted just 14 years, but its impact was immense. He unified lands, defeated invaders, reformed government, encouraged learning, and placed England firmly on the European stage. His was not a flawless kingdom—it fractured after him, as young states often do—but the act of creation was irreversible.

To call him the first king of England is not exaggeration. It is historical truth. His life deserves to be remembered not only in books but in public memory, alongside Alfred, Hastings, and Magna Carta.

A millennium after his coronation, perhaps the time has finally come to lift Æthelstan from the shadows and restore him to his rightful place: the king who made England.

More information: David Woodman, The First King of England: Æthelstan and the Birth of a Kingdom is published by Princeton University Press on 2nd September 2025 (ISBN:9780691249490)