In the span of a single human lifetime, technology has moved at a pace that once seemed impossible. From room-sized computers to pocket-sized supermachines, from handwritten letters to instant communication across oceans, and from early calculators to artificial intelligence that can paint, write, diagnose, and even predict. But one question, once confined to science fiction, now hovers uneasily at the edges of our reality: could AI one day decide who lives and who dies?

This is not only a technical question but also a moral, philosophical, and deeply human dilemma. The thought that a machine—a creation of wires, algorithms, and probability—might hold the power of life and death unsettles us to our core. It evokes fear, awe, and profound curiosity. Yet to understand this possibility, we must peel back the layers of history, science, ethics, and imagination that shape the future of artificial intelligence.

The Origins of Human Judgment in Life-and-Death Decisions

Since the dawn of civilization, human beings have been forced into choices that carried life-and-death consequences. A ruler in ancient times decided whether prisoners lived or died. A doctor in a battlefield hospital chose which wounded soldier to treat first. A judge weighed evidence and passed a sentence. Even an ordinary driver, in a split second, might swerve to avoid one life at the risk of another.

These choices, though agonizing, always had one thing in common: they were made by humans, with human intuition, emotion, and moral frameworks. Mistakes were inevitable, biases ever-present, but the responsibility belonged to us.

AI, however, brings something new into the story. Machines do not feel empathy. They do not hesitate. They do not weep after making a decision. They calculate. And therein lies the heart of the question: should we entrust decisions of life and death to something that cannot feel the weight of those choices?

AI in the Battlefield: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War

One of the most pressing arenas where AI might decide who lives or dies is the battlefield. Militaries around the world are already investing in autonomous drones and robotic systems. These machines can identify targets, track movements, and even fire weapons with minimal human input.

Proponents argue that AI-controlled weapons could reduce human casualties. A machine does not tire, panic, or suffer post-traumatic stress. It can process information faster than any human soldier and strike with precision. But the dark side is chilling: an autonomous drone making its own decision about who is a “threat” could mean the end of human oversight in warfare.

Imagine a scenario: a drone hovers over a crowded city street. It has been programmed to eliminate terrorists. In its camera lens, it detects a figure holding an object shaped like a weapon. Within seconds, it calculates the probability of threat. A child’s toy rifle, a camera tripod, or a real gun—the algorithm must decide. In that instant, human life may be lost because of a machine’s judgment call.

The frightening truth is that once such weapons exist, the pressure to deploy them grows. Nations fear falling behind rivals, and so the logic of war accelerates. Whether humanity likes it or not, AI may soon be deciding life and death in conflicts across the globe.

AI in Medicine: Who Gets to Live When Resources Are Limited?

War is not the only place where AI could face such choices. In hospitals, doctors constantly confront the limits of resources. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, ventilators were in short supply. In disaster zones, there are never enough surgeons, medicine, or blood supplies to treat everyone.

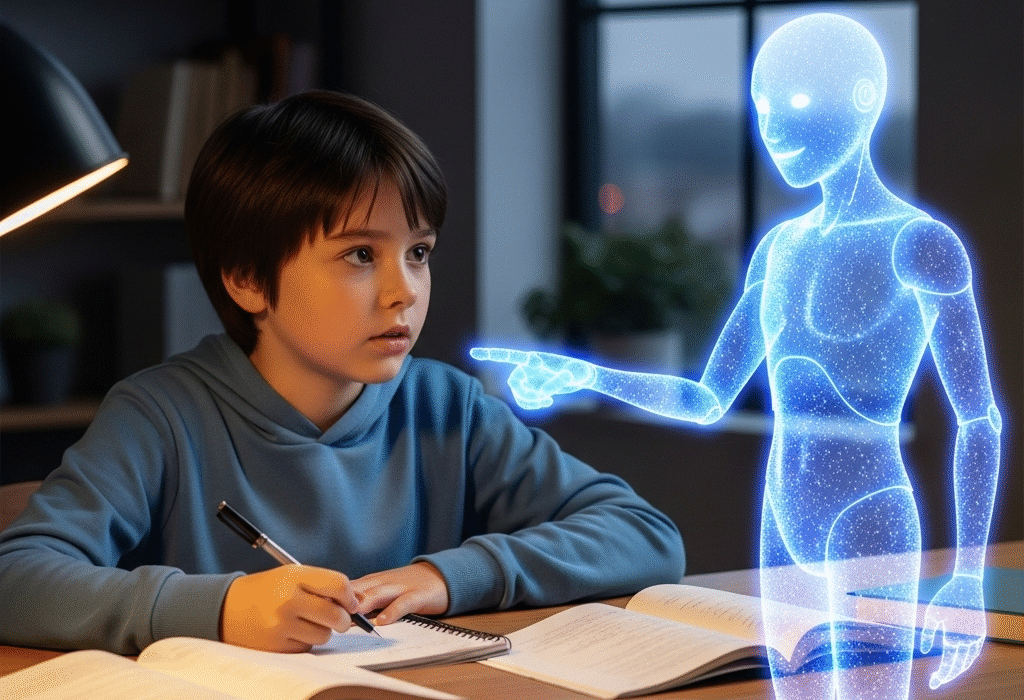

AI systems are already being used to assist in diagnosis, predict patient outcomes, and allocate medical resources. Some algorithms can analyze a patient’s vitals and determine their chances of survival with astonishing accuracy. This could help guide doctors in deciding who should receive limited life-saving treatments.

But here lies the ethical tightrope. Should a machine decide that one person, perhaps younger or healthier, receives the ventilator while another is left to die? Is survival probability the only metric that matters? What about compassion, family circumstances, or the potential for recovery against the odds?

For centuries, medicine has been not just a science but also an art infused with human empathy. If an AI system were to take over triage decisions entirely, medicine risks becoming cold calculation, stripped of the human heart.

Self-Driving Cars and the Modern Trolley Problem

Perhaps the most relatable scenario of AI facing life-and-death choices lies not in war or hospitals, but on our city streets. Self-driving cars are increasingly becoming a reality. But these vehicles face the so-called “trolley problem” in philosophy: if a car must choose between swerving into a group of pedestrians or sacrificing its passenger, what should it do?

AI engineers are being forced to encode moral decisions into their machines. Should the car prioritize the life of its passenger, who trusted it? Or should it prioritize the greater number of lives on the street? And what if those pedestrians include children or elderly individuals?

Unlike human drivers, who react instinctively, AI must be programmed to make these choices systematically. That means human designers are, in effect, writing code that decides who lives and who dies. And once those cars hit the road, their decisions will be executed without hesitation.

The Illusion of Objectivity

At first glance, it might seem that AI could make life-and-death decisions more fairly than humans. After all, algorithms can analyze data without fatigue, bias, or emotional clouding. But this belief is dangerously misleading.

AI systems are only as unbiased as the data they are trained on. History is filled with systemic inequalities—in policing, healthcare, employment, and more. When these patterns are fed into algorithms, they reinforce rather than erase human bias. A medical AI might undervalue patients from marginalized groups because historical data shows worse outcomes, not because they deserve less care. A predictive policing AI might mark certain neighborhoods as “high risk” simply because of biased crime reporting in the past.

Thus, the supposed objectivity of AI is often a mirror reflecting human prejudice. Allowing such systems to decide life-and-death matters risks embedding injustice into the very fabric of technology.

Philosophy and the Weight of a Soul

Beyond the technical and practical lies a deeper philosophical question: can a machine, which does not feel, truly bear the burden of deciding life and death? When a doctor chooses to save a patient, that choice is not just rational—it carries empathy, sorrow, and the weight of responsibility. When a judge spares or condemns, the decision reflects not just laws but human values.

AI, however, has no concept of a soul. It does not tremble at the sight of suffering. It cannot pray for forgiveness or feel guilt. Its decisions are mathematics, not morality. This raises the unsettling possibility that entrusting AI with such power risks hollowing out the very meaning of justice and compassion.

The Temptation of Efficiency

Yet, despite these dangers, there is a powerful temptation to let AI take on life-and-death decisions. Efficiency is seductive. An AI system that can instantly allocate scarce medical supplies, target enemies with precision, or avoid car crashes seems, at first glance, like an undeniable good.

Humans are flawed. We make mistakes, act out of prejudice, and often lack complete information. AI promises to be faster, smarter, and more consistent. This promise has already convinced governments, corporations, and hospitals to increase their reliance on algorithms.

But efficiency without morality is dangerous. A machine that maximizes survival might also decide that the elderly, the sick, or the disabled are “less worthy” of resources. A weapon that eliminates threats without question could lead to massacres without accountability. In chasing efficiency, we risk losing our humanity.

The Struggle for Accountability

One of the most troubling aspects of AI in life-and-death decisions is the question of accountability. When a human doctor, judge, or soldier makes such a choice, they can be held responsible for the outcome. But when an AI system decides, who is to blame?

Is it the programmer who wrote the code? The company that deployed it? The government that approved it? Or is it, chillingly, no one at all?

This diffusion of responsibility creates a moral vacuum. Life and death decisions could become detached from human accountability, leaving victims without justice and societies without answers.

A Future Written by Our Choices Today

The question of whether AI could decide who lives and dies is not just speculative. It is already unfolding around us—in hospitals, in military labs, on city streets. The future will be shaped by the choices we make now.

We can decide to keep humans firmly in control of life-and-death decisions, using AI only as a tool to support—not replace—our moral judgment. Or we can surrender that responsibility to algorithms, trusting in their speed and efficiency even at the cost of empathy and accountability.

The truth is that AI itself does not want or choose anything. It has no desires, no morality, no conscience. The real decision lies with us—whether to grant machines this awesome, terrible power.

The Human Heart at the Center

In the end, the question is not really about AI at all. It is about humanity. What do we value most—efficiency or compassion, survival or dignity, progress or conscience? Technology will continue to advance. Algorithms will grow more powerful. But the decision to entrust them with life-and-death power is ours alone.

To give that power to AI is to gamble with the essence of what it means to be human. To keep it within ourselves is to accept the burden of imperfection but also to preserve the spark of empathy that makes us who we are.

And so, as we stand at the edge of this future, the haunting question remains: could AI decide who lives and who dies? Yes, it could. But should it? That answer is not written in code. It is written in us.