When we imagine life 34,000 years ago, we often picture survival in its most basic form: hunting, gathering, sheltering against the elements. Yet new research from an international team coordinated by Ca’ Foscari University of Venice suggests something far more profound—that even in the depths of the Upper Paleolithic, humans were not only surviving but also experimenting, innovating, and finding beauty in transformation.

For the first time, scientists have discovered traces of indigotin, the deep-blue compound also known as indigo, on ancient stone tools recovered from Dzudzuana Cave in the foothills of the Caucasus in Georgia. This remarkable find shows that early Homo sapiens were intentionally processing plants not just for food, but for more complex purposes—possibly medicine, dyeing, or other cultural practices that went beyond mere survival.

The Blue Molecule That Changed History

Indigotin is not a substance that exists naturally in visible form. It is born from a reaction: when the leaves of the plant Isatis tinctoria L. (commonly called woad) are crushed, enzymes release natural precursors that, when exposed to oxygen, form the striking blue dye. This is not a process that happens by chance. It requires observation, repetition, and cultural transmission.

That indigotin was found on stone tools dating back 34,000 years suggests that early humans already possessed a sophisticated knowledge of plants—recognizing not only what could be eaten but what could be transformed. The discovery pushes back the timeline of humanity’s relationship with dyes and pigments, painting a picture of our ancestors as experimenters, artisans, and innovators.

The Cave in the Caucasus

The tools that yielded this discovery come from Dzudzuana Cave, a site rich in Paleolithic history. Excavations led in the 2000s by an international team—including scholars from Harvard University, the Georgian National Museum, and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem—uncovered layers of human activity stretching across tens of thousands of years.

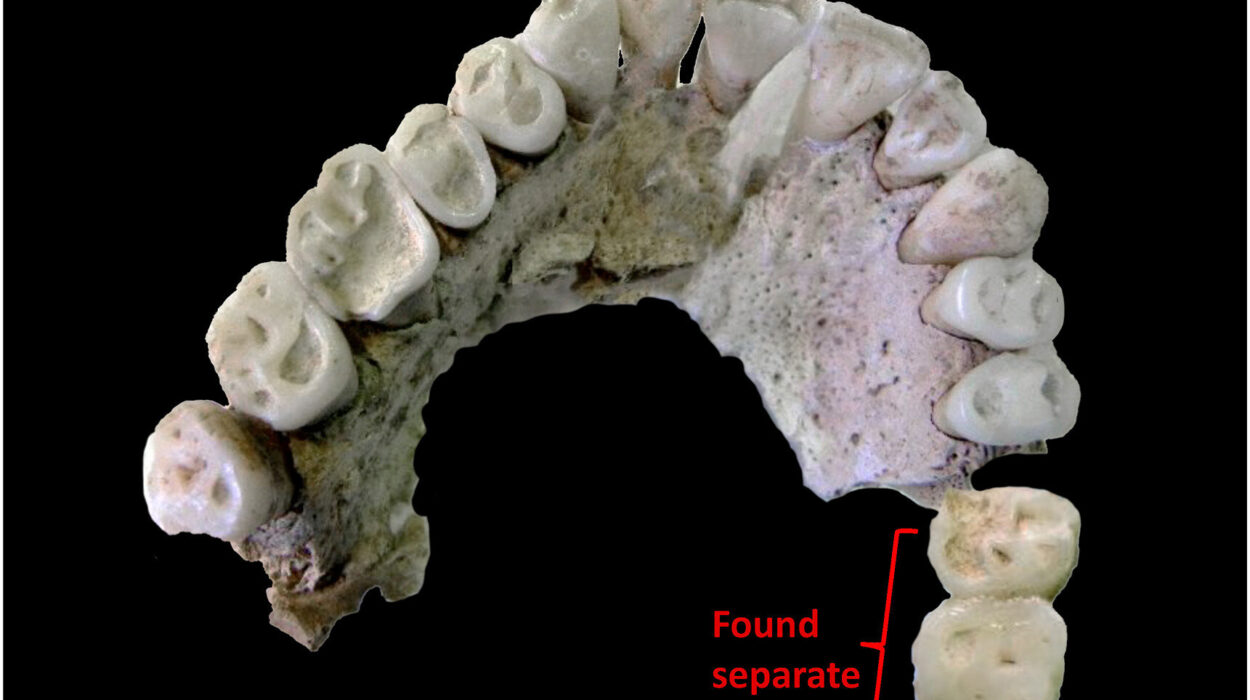

Among the finds were unknapped stone pebbles—tools that were not shaped into blades or points, but instead used for grinding, crushing, and processing softer materials. On these tools, archaeologists spotted faint but curious blue traces, sometimes fibrous, alongside starch grains. Were these remnants of plants? Paints? Medicines? Or something else entirely?

Microscopes and Molecules: Unlocking Ancient Secrets

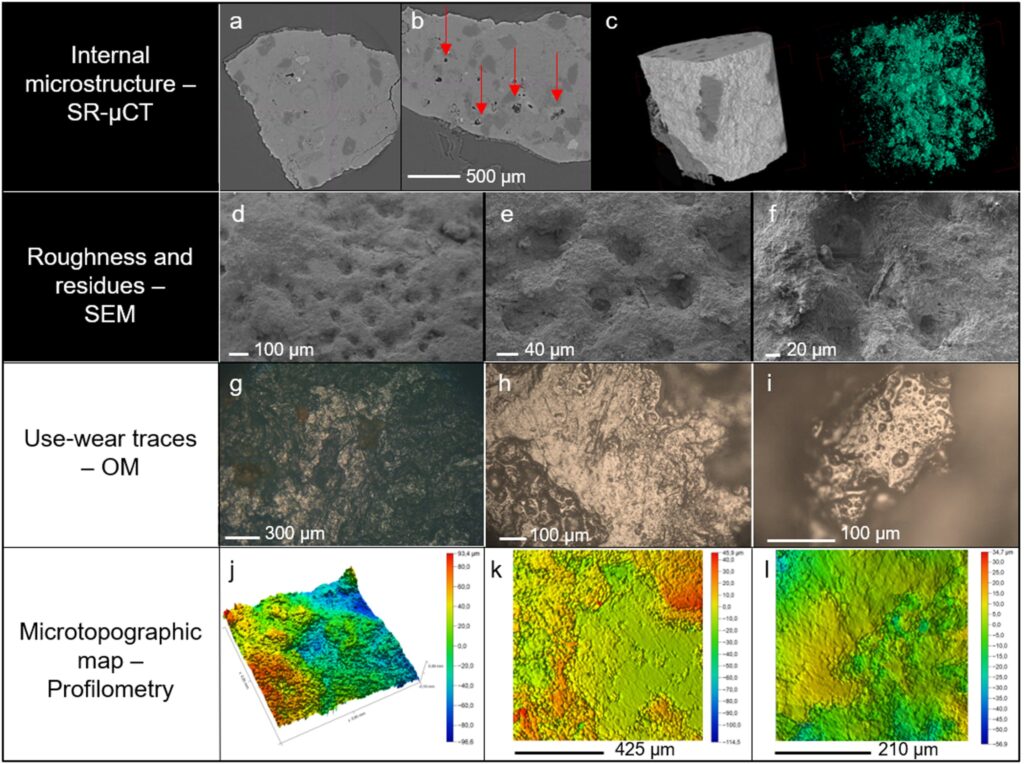

To answer these questions, scientists applied an arsenal of advanced techniques. Optical and confocal microscopy revealed the microscopic residues. Then, using Raman and FTIR spectroscopy, they identified the unmistakable signature of indigotin.

But identifying the dye was only the beginning. How did these molecules become embedded in the pores of the stone? Could the traces simply have been contaminants from the soil? To rule out doubt, researchers used synchrotron radiation micro-CT tomography at Elettra Sincrotrone Trieste, examining both archaeological tools and experimentally made replicas. The tests confirmed that the porous structure of the stones was capable of trapping and preserving plant residues for tens of thousands of years.

The science was clear: the blue on the stones was real, ancient, and intentional.

Experimenting With the Past

To better understand how Paleolithic people might have produced these residues, the research team turned to experimental archaeology. They collected similar pebbles from the Nikrisi River beneath Dzudzuana Cave and cultivated fresh woad (Isatis tinctoria L.) in Verona, Italy. Over three summers, they replicated ancient grinding processes, carefully documenting the kinds of wear patterns and residues that appeared on the stones.

The results were striking. Grinding woad leaves produced the same blue residues and microscopic wear traces found on the original Paleolithic tools. This confirmed that the prehistoric inhabitants of Dzudzuana Cave had deliberately processed plants capable of generating indigotin—34,000 years ago.

Why Blue? The Open Questions

What remains mysterious is how these ancient people used the indigo-like pigment. Did they apply it to fibers, clothing, or skin for decoration or symbolic purposes? Did they use it medicinally, tapping into the plant’s known antibacterial properties? Or was it part of ritual practices that we may never fully understand?

As archaeologist Laura Longo of Ca’ Foscari University explains, this research challenges the old notion that plants in the Paleolithic were only seen as food. Instead, they were “resources for complex operations, likely involving the transformation of perishable materials for different phases of daily life.”

The presence of indigotin suggests that these early humans had a nuanced, experimental relationship with their environment. They recognized that plants held powers beyond nourishment—powers that could change colors, heal wounds, or carry symbolic meaning.

Plants, People, and the Birth of Culture

The discovery of indigotin residues highlights an often-overlooked truth: plants were central to human cultural evolution. Long before agriculture, plants shaped how humans dressed, decorated, healed, and imagined their world.

Woad itself has a long history. In later centuries, it would be used by Celtic tribes to dye fabrics and, according to some accounts, even as body paint. In medieval Europe, it became a cornerstone of the dyeing industry. Its medicinal uses—ranging from wound treatment to anti-inflammatory applications—also endured across cultures.

That Paleolithic humans may have discovered and exploited these properties speaks to their ingenuity. They were not passive foragers but active experimenters, pushing the boundaries of what was possible with the resources at hand.

The Larger Picture of Human Ingenuity

This discovery adds a new layer to our understanding of the Upper Paleolithic. It was an era not only of survival but also of symbolic thought, art, and technological innovation. Cave paintings, beads, and carvings from this period show that humans were already expressing themselves through color, texture, and design. The use of blue dye fits into this broader pattern of creativity and cultural complexity.

It also reshapes how we view early interactions between humans and plants. By proving that plants were processed for purposes beyond food, the study highlights the depth of ecological knowledge our ancestors possessed. They were chemists, healers, and artists long before such words existed.

A Legacy Written in Blue

The faint traces of indigotin on ancient stones are more than just chemical residues. They are whispers from the past, telling us that 34,000 years ago, humans already had a vision of a world transformed by imagination. They saw in plants not just calories but colors, not just survival but possibility.

Science today, using lasers, synchrotrons, and spectroscopy, has brought that vision back to light. And in doing so, it has given us a new appreciation for the sophistication of those who came before us.

The discovery is a reminder that the story of science does not begin in modern laboratories but stretches deep into prehistory, carried in the hands of people who experimented with leaves, stones, and fire. In the blue of indigotin, we glimpse both their ingenuity and our own enduring human curiosity.

More information: Laura Longo et al, Direct evidence for processing Isatis tinctoria L., a non-nutritional plant, 32–34,000 years ago, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0321262