On a quiet farm in rural Minnesota in 1898, a discovery was made that would ignite one of the longest-running debates in North American archaeology. A Swedish immigrant farmer named Olof Öhman, while clearing land near the town of Kensington, unearthed a large slab of stone tangled in the roots of a tree. What made this rock extraordinary was not its size or its setting, but the strange markings carved deeply into its surface—letters that resembled the runes of medieval Scandinavia.

What followed was nothing short of explosive. Could it be possible that Norse explorers, centuries before Columbus, had journeyed deep into the North American continent and left behind a record of their travels? Or was the stone merely an elaborate hoax, born of curiosity, mischief, or even misplaced patriotism?

This stone, now famously known as the Kensington Runestone, has since become a symbol of both wonder and controversy. It sits at the crossroads of archaeology, linguistics, history, and cultural identity, raising profound questions about the nature of evidence, belief, and the stories we tell about the past.

The Discovery in Kensington

The summer of 1898 was an ordinary one for Olof Öhman and his family. Living in Douglas County, Minnesota, they were part of a thriving Scandinavian immigrant community, eking out a living from the rugged farmland of the American Midwest. While clearing trees and stones from his land, Öhman’s axe struck something unusual.

Beneath the roots of a poplar tree lay a rectangular slab of graywacke, roughly 200 pounds in weight, its face covered with inscriptions. To Öhman’s astonishment, the characters looked strikingly like the runes he had seen back in Sweden, symbols associated with the medieval Norse world.

Local curiosity quickly grew. The stone was displayed in nearby towns, attracting attention from scholars, journalists, and fellow immigrants. For many Scandinavians in Minnesota, the idea that their ancestors might have reached America centuries earlier carried powerful emotional weight. It offered a sense of pride and belonging in a new land where they often struggled for recognition.

But from the very beginning, the Kensington Runestone divided opinion. Was it an authentic medieval artifact, or a clever forgery planted in the soil?

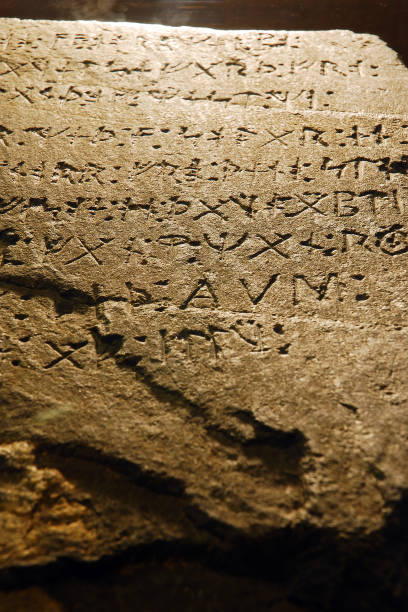

The Inscription

The runes carved into the Kensington stone form a lengthy inscription. Translations vary, but the most commonly accepted rendering reads:

“Eight Götalanders and 22 Northmen on (this?) journey of discovery from Vinland far to the west. We had camp by two shelters one day’s journey north from this stone. We were fishing one day. After we came home we found 10 men red with blood and dead. AVM (Ave Maria) save us from evil. We have 10 men by the sea to look after our ships, 14 days’ journey from this island. Year 1362.”

If authentic, the inscription suggests that a group of Norse explorers traveled deep into the interior of North America—far from the coastal settlements of Greenland and Vinland described in the Icelandic sagas. The year 1362 places their journey nearly 150 years before Columbus’s voyage, and more than 300 years after Leif Erikson’s reputed landing in Newfoundland.

The text is a mixture of medieval Swedish and Norse runes, but with peculiar features. Some of the runes were unfamiliar or inconsistent with known medieval forms, while certain linguistic choices appeared anachronistic, closer to 19th-century Swedish than to 14th-century usage. These irregularities became a central focus of the debate that would engulf the stone for more than a century.

The Case for Authenticity

Supporters of the Kensington Runestone’s authenticity argue that the artifact provides compelling evidence for pre-Columbian Norse exploration of North America beyond the Atlantic seaboard.

Norse Voyages to the New World

It is undisputed that Norse explorers reached North America centuries before Columbus. The site of L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, excavated in the 1960s, confirmed the presence of Norse settlers around the year 1000. This lends credibility to the idea that further explorations could have taken place.

Proponents suggest that the Norse, familiar with river navigation, could have traveled inland through the waterways of Hudson Bay, the Great Lakes, and the Mississippi basin. The inscription’s mention of Vinland and its reference to ships anchored by the sea support this theory.

Tree Root Evidence

When the stone was found, it was entangled in the roots of a tree estimated to be several decades old. Supporters argue that this proves the inscription could not have been made by Olof Öhman himself, since the roots had grown around the stone long before he owned the land.

Runic Specialists

Some Scandinavian scholars in the early 20th century, such as Hjalmar Holand, championed the stone as authentic. Holand spent decades promoting the Runestone, publishing works that connected it to broader Norse exploration and defending its linguistic oddities as natural regional variations of medieval Scandinavian.

Cultural Continuity

Advocates also note that certain features of the inscription, including Christian invocations like Ave Maria, fit the religious culture of 14th-century Scandinavia. The blending of runes with Latin letters is consistent with transitional literacy practices of the era.

The Case Against Authenticity

Skeptics, however, argue that the Kensington Runestone is a 19th-century hoax, created either by Öhman or by someone in his community.

Linguistic Anachronisms

The strongest argument against authenticity is linguistic. Scholars note that many of the words and grammatical structures on the stone resemble modern Swedish rather than medieval forms. Certain phrases, such as opdagelsefard (“journey of discovery”), are seen as distinctly modern, unlikely to have been used in the 14th century.

Runic Inconsistencies

Many runes on the stone do not match known medieval symbols. Some appear to be invented or derived from 19th-century rune charts found in Scandinavian books popular among immigrants. Critics argue this suggests a forger familiar with rune alphabets but not with medieval usage.

Lack of Corroborating Evidence

Despite extensive archaeological surveys, no other artifacts or settlements connected to Norse explorers have been found in Minnesota or the surrounding region. Without corroborating evidence, the stone stands alone, casting doubt on its extraordinary claims.

Olof Öhman’s Background

Skeptics often point out that Öhman, though by all accounts a hardworking farmer, was literate and familiar with Scandinavian folklore. He owned books that contained runic alphabets and had the means to carve the stone himself. Some suggest he created the Runestone as a practical joke or as a way to attract attention.

The Cultural Context

To understand the Runestone, it is essential to consider the cultural atmosphere of late 19th-century Minnesota. Scandinavian immigrants faced challenges in a new land, often marginalized by the dominant Anglo-American culture. The discovery of an artifact linking their ancestors to America centuries before Columbus offered a powerful symbol of legitimacy and pride.

For many, the Runestone was more than a rock—it was proof that their heritage was woven into the very soil of their adopted homeland. This explains why the stone was embraced passionately by the immigrant community, even as scholars dismissed it.

The Role of Hjalmar Holand

No figure is more closely associated with the Runestone’s promotion than Hjalmar Holand, a Norwegian-American historian. From the early 1900s until his death in 1963, Holand tirelessly argued for the stone’s authenticity. He published extensively, gave lectures, and even petitioned Congress to recognize Norse exploration as part of American history.

Holand’s efforts ensured that the Runestone became a cultural icon, particularly in Minnesota, where it remains celebrated in festivals, museums, and local lore. Yet Holand’s work also entrenched the controversy, as professional linguists and archaeologists criticized his methods and conclusions.

Modern Scientific Studies

In the 20th and 21st centuries, scientific techniques have been applied to the Runestone. Petrological studies confirm that the stone itself is local Minnesota graywacke, consistent with the find site. Weathering analysis suggests the carving is not recent, though determining exact age from erosion remains difficult.

Linguistic studies continue to challenge the inscription, but some researchers argue that earlier dismissals may have been too rigid, failing to account for dialectal diversity in medieval Scandinavian. A few specialists suggest that while unusual, the language could conceivably reflect a transitional or regional form.

Despite these efforts, no definitive conclusion has been reached. The stone remains an enigma—its authenticity neither conclusively proven nor entirely disproven.

The Runestone in Popular Culture

Beyond academia, the Kensington Runestone has taken on a life of its own. It features prominently in Minnesota tourism, displayed at the Runestone Museum in Alexandria. It has inspired novels, documentaries, and even conspiracy theories about hidden Norse maps or secret voyages.

For some, the Runestone symbolizes suppressed history—a reminder that mainstream narratives can overlook alternative possibilities. For others, it is a cautionary tale about the dangers of wishful thinking and the need for rigorous scholarship.

Why the Debate Persists

The Kensington Runestone endures as a controversy because it touches on deep questions. At its heart lies the tantalizing possibility that history is far more complex than we imagine. Did Norse explorers truly penetrate the heart of North America in the 14th century, leaving behind a carved message in Minnesota soil? Or is the stone simply a reflection of immigrant identity, shaped by nostalgia and imagination?

The absence of definitive evidence ensures that the debate continues. Archaeologists demand corroboration, while enthusiasts point to the stone’s existence as proof in itself. In the absence of certainty, the Runestone lives in the fertile space between fact and legend.

Lessons from the Kensington Runestone

Whether authentic or not, the Kensington Runestone offers profound lessons. It demonstrates how artifacts can shape identity and meaning, transcending their material form. It reveals the interplay between scholarship and community belief, where the authority of experts collides with the power of cultural pride.

It also challenges us to reflect on how we construct history. What do we accept as evidence? How do we balance skepticism with openness to new possibilities? The Runestone reminds us that history is not only about facts, but also about the stories we tell and the values we assign to them.

Conclusion: A Stone Between Worlds

The Kensington Runestone is more than a slab of carved rock. It is a symbol of mystery, identity, and the search for truth. Buried in Minnesota soil, it has unearthed not only debates about Norse exploration but also the deeper human need to connect with the past.

Whether a medieval artifact or a 19th-century creation, the stone has fulfilled a powerful role. It has inspired generations to imagine lost voyages, hidden histories, and the possibility that the world is larger and stranger than we know.

In the end, perhaps the true significance of the Kensington Runestone lies not in resolving its authenticity, but in acknowledging the questions it raises. It stands as a reminder that history is not static, but alive—shaped by discovery, controversy, and the enduring human hunger for meaning.