For thousands of years, humans have grappled with the question of how to preserve the dead. From the golden tombs of Egypt to the chillingly lifelike relics in European cathedrals, embalming has served as both ritual and remembrance, science and spirituality. Yet even in this well-explored realm, surprises emerge from time to time—fragments of forgotten wisdom buried in bone and cloth.

In the quaint Austrian village of St. Thomas am Blasenstein, nestled among rolling hills and time-worn churches, a centuries-old secret lay in silence beneath the floor of a parish crypt. The figure, preserved in an uncanny state, had long stirred rumors and curiosity among locals and visitors alike. Who was he? How did he remain so astonishingly intact, even after nearly three centuries? The answers, as it turns out, defy conventional embalming knowledge and open a window into a little-known funerary practice.

A Cryptic Puzzle Comes to Light

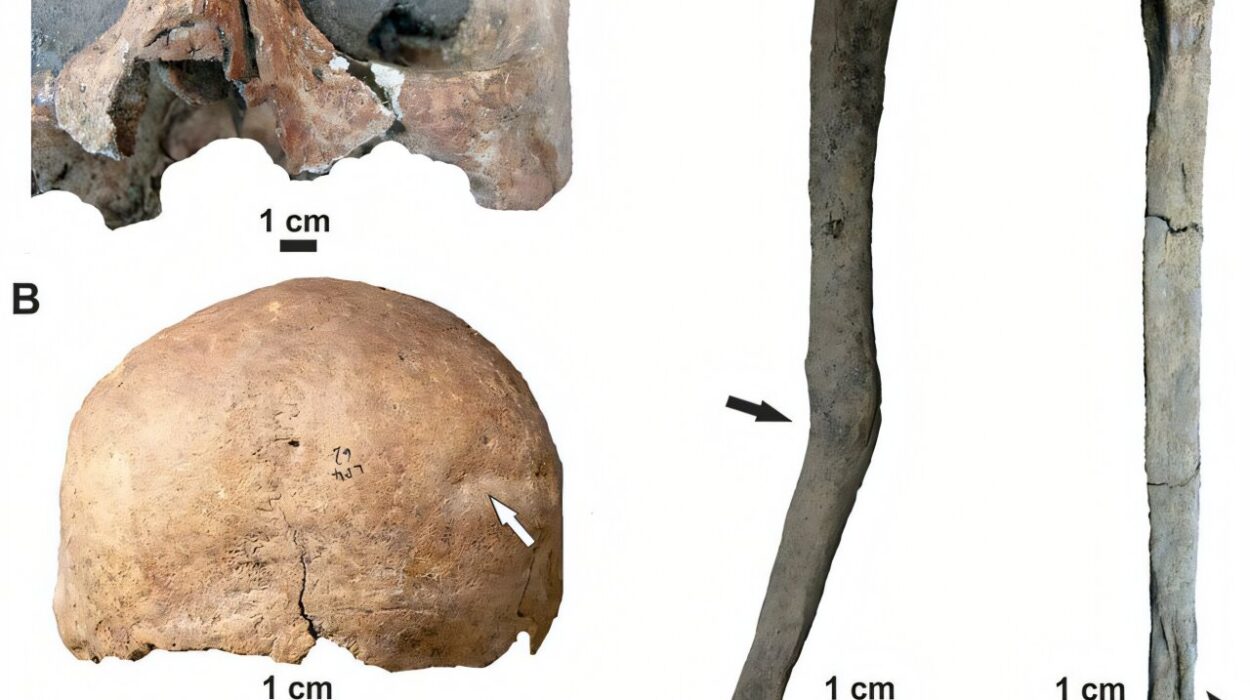

The story begins with a corpse. Not just any corpse, but one that had endured the slow churn of time with remarkable grace. Sheltered in the crypt of St. Thomas am Blasenstein, the mummy appeared stiff but recognizable—its torso preserved in a leathery state, its limbs and head less so, a visible contrast that puzzled casual observers and experts alike.

To solve the mystery, a group of international researchers, led by Dr. Andreas Nerlich of Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich, launched a comprehensive investigation. Their work, recently published in Frontiers in Medicine, was more than an archaeological footnote; it was a forensic odyssey that spanned centuries, peering deep into the chemistry, culture, and ecology of 18th-century Austria.

A Vicar Revealed

Using a combination of advanced diagnostic techniques—including CT scanning, focal autopsy, and radiocarbon dating—the researchers began to peel back the layers of history. What they found was both unexpected and illuminating.

The remarkably well-preserved mummy, they concluded, was none other than Franz Xaver Sidler von Rosenegg, a parish vicar who had died in 1746. The identity was not simply guessed or inferred; it was established through a mosaic of evidence—carbon dating that placed the death between 1734 and 1780, analysis of dietary isotopes matching the Central European region, and even clues embedded in his bones and lifestyle.

This wasn’t just a preserved body—it was a biography written in flesh, an intimate reconstruction of a man who once gave sermons, breathed village air, and fell prey to the same mortal limits as us all.

An Embalming Method Unlike Any Other

But what truly astonished the team wasn’t the identity of the vicar—it was the method by which his body had been embalmed. It was, by all accounts, unprecedented.

Whereas traditional embalming techniques often involved surgical incisions, organ removal, and surface treatments with resins or oils, Sidler’s body had been prepared from the inside out, through a method as peculiar as it was effective.

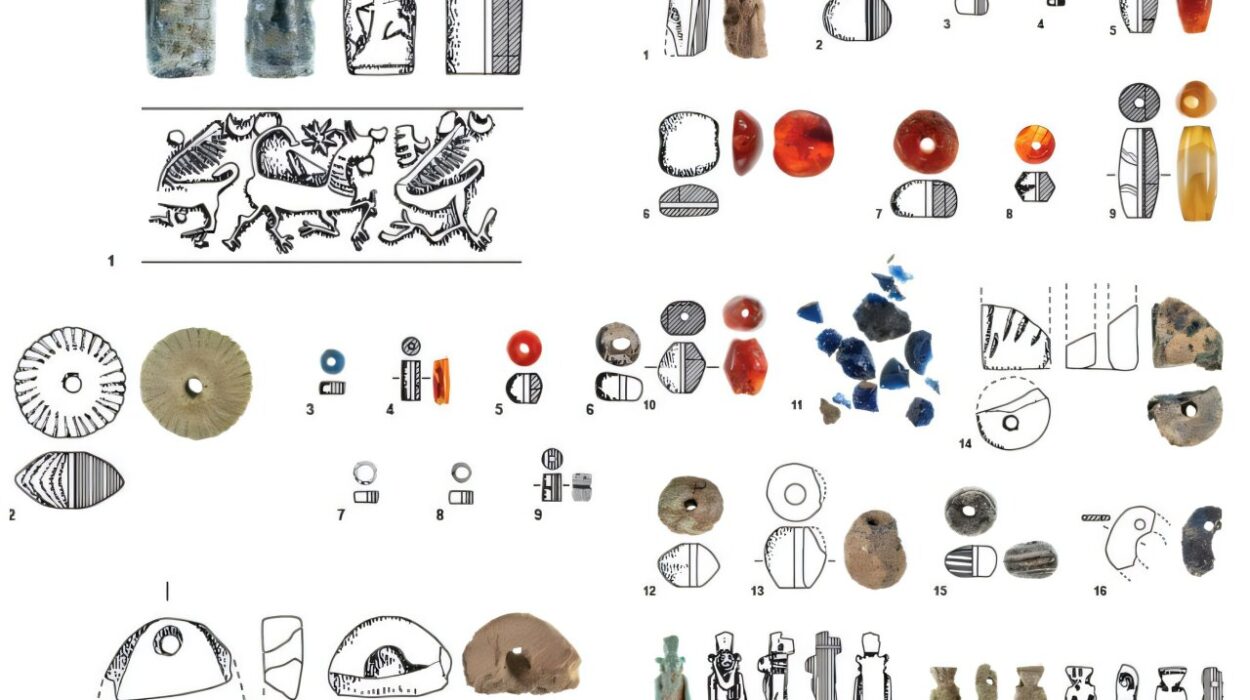

The abdominal cavity had been packed—stuffed, to be exact—via the rectum, using a curious mix of wood chips, tree twigs, and dry fabric fragments made from linen, hemp, and flax. These humble materials, all locally sourced and abundant in the region, served a vital function: they absorbed internal moisture that otherwise would have spurred decomposition.

But there was more. Toxicological tests detected traces of zinc chloride, a chemical compound known for its potent drying and antimicrobial properties. Combined with the absorbent mixture, this application created a self-contained drying system that mummified the body from within.

“The body wasn’t opened in the usual sense,” Dr. Nerlich explained. “The embalming materials were inserted through the rectal canal—an approach that may have gone unnoticed in other historical cases, especially if external signs of tampering were obliterated by later decay.”

This discreet yet highly effective method may have been more widespread than previously thought. However, due to the delicate and often degraded nature of historical remains, it likely went undocumented and unrecognized—until now.

The Mystery Bead and a Monastic Clue

Among the unusual finds inside the mummy was a single small glass bead, pierced with holes on both ends. It might seem a trivial detail, yet such artifacts often carry symbolic weight. The researchers hypothesize that this could be part of a monastic garment—a rosary or devotional item that slipped inside during burial preparation.

Though the exact purpose of the bead remains uncertain, its presence adds a touch of human poignancy—a final token, perhaps, buried with the dead in hopes of protection, memory, or grace.

Piecing Together a Life from the Bones

While the embalming method was the centerpiece of the discovery, the team’s interdisciplinary approach also painted a remarkably vivid picture of Sidler’s life—his diet, health, daily habits, and probable cause of death.

Isotope analysis revealed a diet rich in animal products, local grains, and inland fish—a high-status menu reflecting both access and privilege. This matched well with his position as a vicar in a relatively prosperous region. Yet there were signs of hardship, too. Towards the end of his life, Sidler appears to have experienced nutritional stress, possibly linked to the War of Austrian Succession (1740–1748), which disrupted food supplies and trade routes across Europe.

Physiological markers also revealed minimal physical labor, consistent with a priest’s sedentary lifestyle. However, the skeleton bore evidence of chronic tobacco use—common among clerics of the time—and likely suffered from pulmonary tuberculosis, a disease that often flourished in cold, close quarters.

In a tragic but fitting twist, this man of the cloth likely succumbed to a disease of the lungs—ironically, the very organ through which he had preached and sung for decades.

Death, Preservation, and Unfinished Journeys

Historical texts offer occasional clues about funeral practices during this period. There are vague references to bodies being “prepared” for transportation or for delayed burial, often to fulfill a final wish or to allow time for elaborate funeral rites. Dr. Nerlich and his colleagues speculate that Sidler may have been embalmed for transport back to a home abbey or family crypt—a plan that was abandoned or failed, leaving the vicar in eternal residence beneath the church floor.

In this light, the embalming was not merely a ritual act but a practical solution to a logistical problem. The unusual internal preservation method would have helped stabilize the corpse during a slow carriage journey over unpaved roads. Ironically, the failed mission may have inadvertently created one of Europe’s best-preserved mummies.

The Forgotten Science of the Dead

The embalming technique discovered in Sidler’s remains doesn’t appear in standard historical records, nor does it resemble the documented practices of more famous mummification traditions. This makes it an exciting and completely novel entry into the annals of mortuary science.

Could similar techniques have been used in other rural European contexts—perhaps in other villages, crypts, or unexcavated tombs? The answer, tantalizingly, is yes. But until more mummies are examined with the same level of scientific rigor, this remains an open field for future investigation.

An Unlikely Legacy

Franz Xaver Sidler von Rosenegg may not have imagined that his body would become the subject of 21st-century headlines, international research, and radiographic scrutiny. In his lifetime, he was a local priest—respected, no doubt, but not famous. And yet, in death, he became a scientific trailblazer, his very tissues a living archive of forgotten practices.

In an age obsessed with technological preservation—from cloud storage to cryonics—it’s oddly poetic that the secret to long-lasting preservation might have rested in fir twigs, flax, and a sprinkle of zinc chloride, wielded not in a lab, but in the quiet backroom of an 18th-century rectory.

A Testament to Interdisciplinary Curiosity

This discovery wasn’t just a triumph of archaeology or forensic science—it was a demonstration of interdisciplinary collaboration at its best. Biologists, pathologists, historians, chemists, and anthropologists all brought their skills to bear on a single corpse, transforming it from an object of local legend into a globally significant artifact.

And in doing so, they reminded us of the enduring value of asking questions about the past, even when the answers seem buried, incomplete, or implausible.

Because sometimes, the truth lies not in what we expect to find, but in what we almost missed—hidden in wood chips and silence, in the rectal canal of an old vicar’s corpse, waiting for someone to look closely enough to understand.

Reference: The Mystery of the “Air-dried Chaplain” solved: the Life and “Afterlife” of an unusual Human Mummy from 18 th century Austria, Frontiers in Medicine (2025). DOI: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1560050