Deep beneath the sedimentary layers of western Portugal, within the fossil-rich Ulsa quarry of the Freixial Formation, scientists have uncovered a remarkable clue to our planet’s distant past—a new species of multituberculate mammal named Cambelodon torreensis. This tiny creature, which roamed Earth during the Late Jurassic around 145 million years ago, is offering researchers new insight into a group of mammals whose evolutionary history continues to intrigue and perplex paleontologists.

The discovery, recently published in Papers in Palaeontology, may seem like just another addition to the fossil catalog. But in reality, it opens a window into the ancient world of mammals that lived in the shadow of the dinosaurs, reveals complex evolutionary adaptations in tooth development, and reshapes our understanding of one of the most enduring mammalian lineages—Multituberculata.

Let us journey back to the time of Cambelodon torreensis and explore the fascinating story behind this tiny jawbone with a monumental scientific impact.

Echoes from Laurasia: The Legacy of the Multituberculates

Before delving into the significance of C. torreensis, it’s essential to understand the ancient mammalian dynasty it belonged to. The order Multituberculata was no minor evolutionary footnote. It was a lineage of small to medium-sized mammals that thrived for an astonishing 100 million years—outliving the dinosaurs and persisting well into the early days of placental mammal dominance.

Their success was, in large part, due to their specialized dentition. Unlike most other mammals, multituberculates bore complex cheek teeth—hence the name—that allowed them to grind tough plant material with efficiency. This trait is preserved in exquisite detail in the fossil record, especially in sites like the famed Guimarota coal mine in central Portugal, where over a dozen multituberculate species have been identified.

According to Victor Carvalho, lead author of the recent study, multituberculates were evolutionary marvels, demonstrating remarkable adaptability across continents and epochs. “They show an impressive array of dental specializations,” he notes, “which speaks to their ecological versatility and success.”

Yet, despite their long-standing reign, the evolutionary relationships among multituberculate families—and in particular, the enigmatic Pinheirodontidae—remain murky. That’s why discoveries like Cambelodon torreensis are vital: they provide missing pieces of a puzzle that is both scientifically tantalizing and evolutionarily crucial.

The Fossil Find: A Quarry’s Hidden Treasure

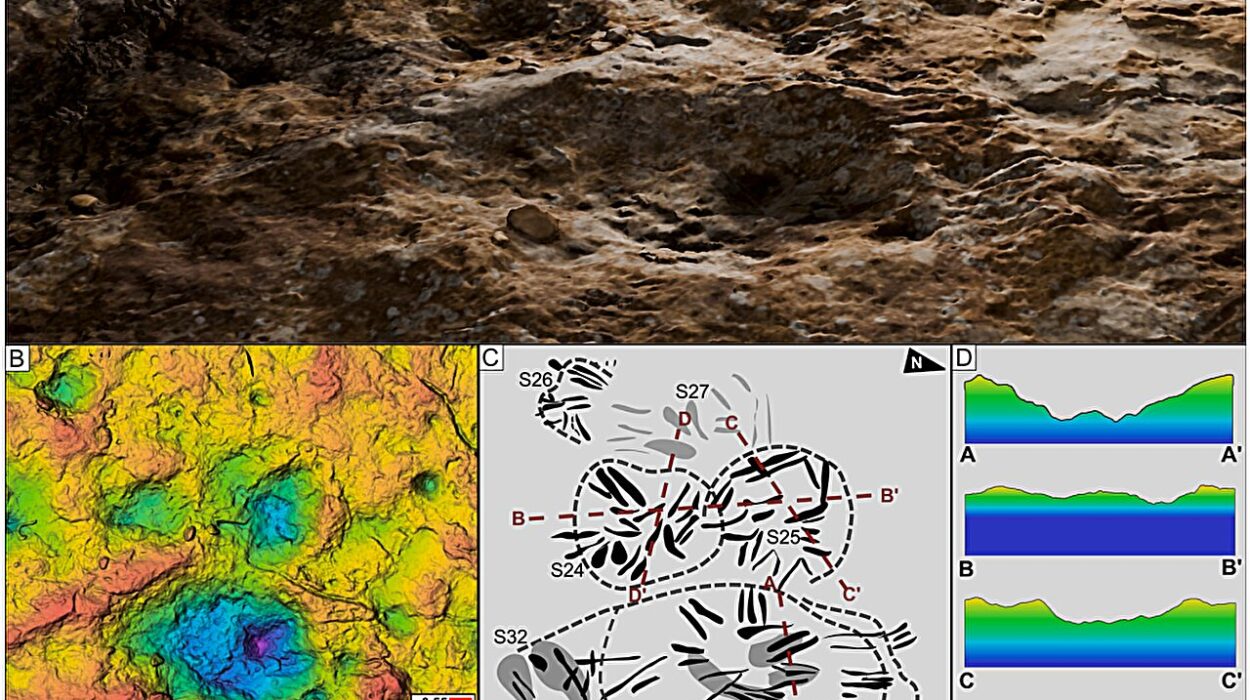

The story of C. torreensis begins not with a mighty expedition, but with a quiet discovery. In 2021, Graça Ramalheiro unearthed the Ulsa quarry in the village of São Pedro da Cadeira, Portugal. Located within the Tithonian-stage Freixial Formation, this site proved to be a time capsule of Jurassic biodiversity, harboring both macro- and microfossils.

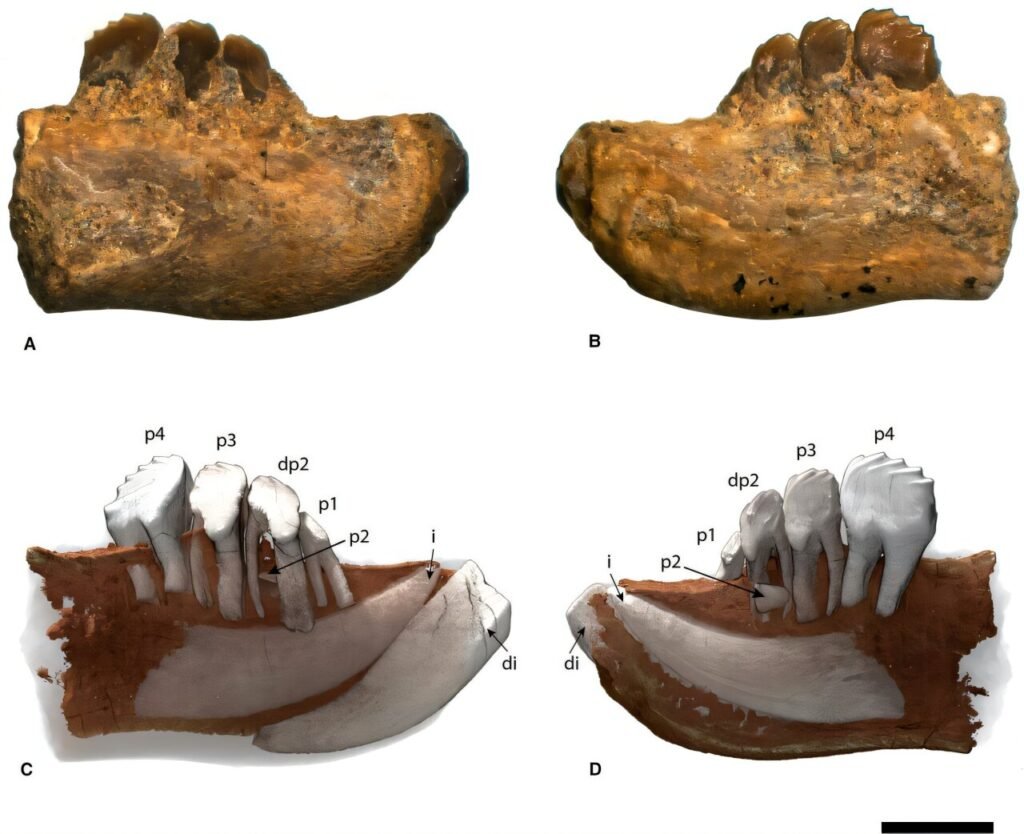

Among the extracted material was a limestone block that made its way to the laboratory of the Sociedade de História Natural (SHN). Within that unassuming block lay a treasure: a right hemimandible, specimen SHN.830, partially embedded in rock but remarkably well-preserved.

Unlike typical isolated teeth—the standard fare of pinheirodontid fossil finds—this was a nearly complete juvenile jawbone, with both incisors and molariform teeth in situ. And with it came not just the specimen itself, but an evolutionary riddle encoded in dental enamel.

Decoding the Jaw: Teeth as Evolutionary Textbooks

At first glance, the jaw of C. torreensis appeared similar to other multituberculates from the region. Portugal’s Guimarota mine had yielded a rich record, including species of Paulchoffatiidae and other multituberculate families, which served as critical reference points.

However, SHN.830 resisted easy classification.

Detailed analysis of the premolars—specifically the third and fourth (p3 and p4)—revealed a set of five cusps or projections on each tooth, along with nine basal cusps on p4. These were not features known from other multituberculates. The triangular lobes, cusp number, and jaw morphology all pointed to something new.

Though comparisons were made to paulchoffatiids, plagiaulacids, and even allodontids, SHN.830’s dentition was distinct. Carvalho and his team concluded that they were looking at a new species—one that expanded not just the known range of the Pinheirodontidae family, but also its anatomical and developmental diversity.

The new species was named Cambelodon torreensis, its genus a nod to the region of Torres Vedras, where the quarry lies. This identification marked a rare and significant step forward in pinheirodontid research, a group previously known only from scattered dental remnants.

A Tooth Tale: Juvenile Replacement Patterns Rewritten

The age of the C. torreensis specimen was particularly illuminating. As a juvenile, it offered a rare glimpse into tooth eruption patterns—a developmental process that reveals much about evolutionary pathways.

In modern mammals, teeth erupt in an orderly, front-to-back sequence. In contrast, most multituberculates display a posterior-to-anterior replacement pattern. Stranger still, a handful of multituberculate species—such as Kielanodon hopsoni and Rugosodon eurasiaticus—showed an even more unusual pattern: non-sequential posterior-to-anterior replacement.

That means teeth erupted from the back forward but skipped positions in an irregular order. Carvalho’s team found evidence that C. torreensis followed this rare pattern too. “It’s exceptionally rare,” he explains, “and points to a derived, rather than ancestral, trait.”

This insight challenges previous assumptions that such tooth replacement strategies were confined to the Paulchoffatiidae family and pushes the evolutionary experimentation of multituberculates further back into the Jurassic than previously thought.

The implications are striking. Not only does it suggest that non-sequential replacement evolved multiple times or was more widespread than believed—it also hints at rapid developmental adaptation in early mammals navigating their ecological niches under dinosaur-dominated skies.

Piecing Together the Body: Beyond the Teeth

SHN.830 was not alone in the Ulsa block. Alongside it, researchers recovered postcranial bones, including vertebrae and limb fragments. None have yet been definitively assigned to C. torreensis, but they suggest a multispecies bonebed with individuals at various growth stages.

If even one of these bones can be confidently linked to Cambelodon, it would represent a major step forward. Postcranial material from basal multituberculates is notoriously rare. Carvalho notes that fewer than six such elements have ever been recovered from the Guimarota site, making these new finds potentially groundbreaking.

In addition to the multituberculates, bones belonging to dryolestids—another group of Mesozoic mammals—were found in the Ulsa quarry, highlighting the diversity of the ecosystem.

The site, it seems, was a prehistoric crossroads, preserving the delicate remains of creatures that rarely fossilize well. And it holds the promise of much more to come.

Looking Ahead: Paleontology in Progress

The discovery of Cambelodon torreensis is not the end of the story—it’s the beginning of a broader paleobiological reconstruction. Carvalho and colleagues are already planning a comprehensive re-evaluation of the Pinheirodontidae family, aided by new material and improved analytical techniques.

The Ulsa quarry remains an active field of study, with many fossils still awaiting classification. And a newly discovered bonebed from even older deposits in the Freixial Formation, rich in microfossils and palynological (pollen-based) data, promises to expand our view of Jurassic ecosystems even further.

With each fossil recovered, catalogued, and examined, scientists edge closer to a clearer understanding of early mammalian life—its adaptations, its environments, and its evolutionary detours.

A Tiny Jaw with a Mighty Message

Cambelodon torreensis may have been no larger than a modern rodent, but its significance looms large. This juvenile jaw, weathered by time yet perfectly poised in the rock, speaks to a world of mammals striving and adapting in a dinosaur-ruled Earth. It tells a story of developmental quirks, evolutionary divergence, and the subtle power of teeth to unlock the secrets of deep time.

In paleontology, the smallest fossils often yield the largest truths. With C. torreensis, we are reminded that the legacy of life is not just written in stone—it’s etched in enamel, shaped by survival, and waiting patiently to be rediscovered.

Reference: Victor F. Carvalho et al, Cambelodon torreensis, a new pinheirodontid multituberculate from the Upper Jurassic of western Portugal, Papers in Palaeontology (2025). DOI: 10.1002/spp2.70012