High in the rugged peaks of the Andes Mountains, where snow-capped summits kiss the sky and valleys echo with rushing rivers, an empire once thrived that defied the extremes of nature. The Inca Empire, known to its people as Tawantinsuyu, meaning “the land of the four quarters,” rose from the heart of South America to become one of the most remarkable civilizations of the pre-Columbian world.

The Incas built not only cities but a system of life that endured across mountains, deserts, and rainforests. From humble beginnings in the Cusco Valley around the early 13th century, they expanded to rule the largest empire in the Americas, stretching over 4,000 kilometers along the spine of the Andes. With no written language, no iron tools, no wheeled vehicles, and no horses, they accomplished feats that continue to astonish modern science.

To speak of the Inca Empire is to speak of ingenuity, resilience, and vision. Their achievements in architecture, agriculture, administration, and astronomy demonstrate a civilization deeply attuned to its environment, capable of bending nature to human needs without breaking it. Their story is one of triumph and tragedy, of brilliance extinguished too soon by conquest, but not before leaving a legacy etched into stone, earth, and memory.

The Sacred Origins of the Inca

Like many great civilizations, the Incas traced their origins not only to history but to myth. According to Inca tradition, their ancestors emerged from sacred places tied to the land itself. One legend tells of the first Inca, Manco Cápac, and his sister-wife Mama Ocllo, children of the Sun god Inti, who rose from the waters of Lake Titicaca to bring civilization to humankind. Another version tells of Ayar siblings who emerged from a cave at Pacaritambo, guided by divine will to settle in Cusco, the future capital of the empire.

Whether divine or human, the early Incas were one of many small groups inhabiting the Cusco Valley. Surrounded by rival chiefdoms, they slowly consolidated power through alliances, warfare, and diplomacy. By the 15th century, under the leadership of the visionary ruler Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui, the Incas transformed from a minor tribe into an imperial power. Pachacuti reorganized the state, expanded its territories, and established Cusco as a magnificent capital—the “navel of the world.”

Tawantinsuyu: The Four Regions of an Empire

The Inca Empire was not a single kingdom but a federation of lands woven together into one political and cultural fabric. Tawantinsuyu, “the four quarters together,” divided the empire into four great regions:

- Chinchaysuyu, stretching northward toward present-day Ecuador.

- Antisuyu, reaching into the eastern jungles of the Amazon basin.

- Collasuyu, expanding southward into Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina.

- Cuntisuyu, extending westward toward the Pacific coast.

At the heart of this vast realm lay Cusco, designed as a sacred and political center, its layout resembling the shape of a puma, a revered animal of power. From Cusco, the Inca ruler—the Sapa Inca, considered a living descendant of the Sun—commanded the empire with divine authority. His word carried not only political weight but spiritual force, uniting diverse peoples under a common cosmology.

Engineering the Impossible

The Andes are among the most formidable landscapes on Earth. Towering mountains, steep valleys, arid deserts, and unpredictable earthquakes would seem to challenge the very possibility of empire. Yet the Incas turned obstacles into opportunities, mastering their environment with engineering genius.

They built an extensive network of roads—over 40,000 kilometers long—that connected their empire like arteries. Known as the Qhapaq Ñan, this road system traversed cliffs, deserts, rivers, and snowbound passes, linking far-flung provinces to Cusco. Rope suspension bridges, woven from plant fibers, spanned deep gorges, and relay runners known as chasquis carried messages across the empire with astonishing speed.

In their cities and temples, the Incas demonstrated stonework of unparalleled precision. At sites like Sacsayhuamán and Ollantaytambo, massive stone blocks—some weighing over 100 tons—were fitted together so perfectly that not even a blade of grass could slip between them. These constructions, resistant to earthquakes, reveal both architectural mastery and a profound understanding of the land’s seismic nature.

The jewel of Inca engineering is Machu Picchu, the “lost city” perched on a ridge above the Urubamba River. Built in the 15th century, it combines terraces, temples, fountains, and dwellings in harmony with the mountain landscape. Machu Picchu was not merely a city but a sacred sanctuary, a place where nature and human design blended seamlessly.

Feeding an Empire: Inca Agriculture

Sustaining millions of people across diverse and often harsh environments required agricultural innovation on an extraordinary scale. The Incas transformed their landscapes into living larders. Terraces carved into mountainsides created fertile plots that captured rainfall and prevented soil erosion. Irrigation systems channeled water across valleys, while storage facilities called qullqas preserved surplus crops for times of scarcity.

The Incas cultivated a staggering variety of crops adapted to different climates and elevations. Potatoes, with thousands of varieties, thrived in the highlands. Maize grew in valleys and warmer regions. Quinoa, beans, and peppers added diversity, while coca leaves, sacred and energizing, played both economic and spiritual roles.

Domesticated animals like llamas and alpacas provided wool, meat, and transport, while guinea pigs served as a household food source. The agricultural surplus not only fed the empire but underpinned its political power, enabling the state to redistribute food in times of famine and to support armies on distant campaigns.

The Social Fabric of the Inca World

The success of the Inca Empire was not built on conquest alone but on a complex social structure that balanced unity with diversity. At the core of Inca society was the ayllu, a kinship-based community that shared land, labor, and resources. The ayllu represented both a social and economic unit, grounded in reciprocity and collective responsibility.

Above the ayllu, the empire functioned through a system of tribute labor called mit’a. Every subject contributed work to state projects—building roads, farming communal lands, or serving in the military—in exchange for protection and access to resources. This system created vast infrastructure without the need for currency or markets, relying instead on labor as the fundamental economic unit.

At the top of the hierarchy stood the Sapa Inca and his royal lineage, supported by nobles and administrators who governed provinces. Religion reinforced political authority, with the worship of Inti, the Sun god, binding subjects to the divine order embodied by the ruler. Priests, astronomers, and ritual specialists played vital roles in maintaining cosmic balance.

Knowledge Without Writing

One of the greatest mysteries of the Inca Empire is its administration without a written language. Instead, the Incas developed an ingenious system called quipu, a series of knotted strings of different colors used to record information. Quipus tracked census data, tribute, agricultural yields, and even narratives. Though their full meaning is still being decoded, quipus reveal a sophisticated system of record-keeping that defied the absence of conventional writing.

Oral tradition also played a vital role. Stories, histories, and laws were memorized and passed down through generations by amautas, wise men who preserved knowledge through performance and teaching. This reliance on memory and symbol created a living culture of continuity that thrived without alphabet or script.

Science, Medicine, and Astronomy

The Incas were not only builders and farmers but keen observers of the natural world. Their medical practices combined herbal remedies with surgical techniques such as trepanation—removing sections of skull bone to treat injuries. Remarkably, survival rates for these procedures were high, indicating both skill and knowledge of antiseptic plants.

Astronomy guided Inca agriculture and religion. Observatories like those at Machu Picchu tracked solstices and equinoxes, aligning temples and windows with the sun’s path. The Incas divided the sky into constellations, including dark patches within the Milky Way that represented sacred animals. The heavens were not distant but part of the living cosmos, connected to rivers, mountains, and cycles of time.

Spirituality and the Sacred Landscape

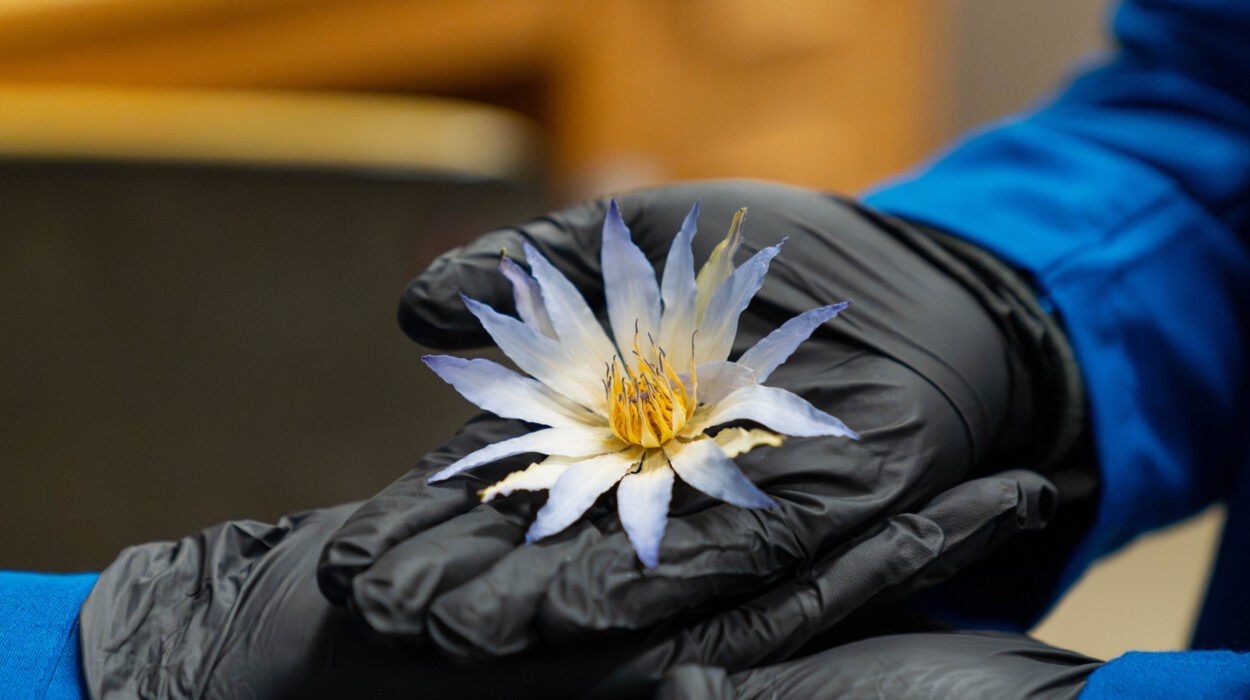

For the Incas, the world was alive with spirit. They practiced a form of animism, seeing sacred essence in mountains, rivers, stones, and animals. These sacred entities, called huacas, were revered through offerings and ceremonies. The Andes themselves were not merely geography but a sacred landscape, with towering peaks embodying deities known as apus.

The Sun, Inti, was the central deity, worshipped in grand festivals such as Inti Raymi, the celebration of the winter solstice. The Moon, the Earth goddess Pachamama, and the creator god Viracocha also held important places in Inca cosmology. Rituals involved music, dance, sacrifices, and offerings of food, textiles, or animals.

In extreme cases, human sacrifice was performed, often involving children in ceremonies known as capacocha, chosen for their purity and offered on mountaintops to secure fertility, rain, or victory. These practices reflected the Incas’ profound belief in reciprocity with the divine—a cosmic exchange where humans gave to the gods in order to receive life’s blessings.

The Spanish Conquest and the Fall of an Empire

In the early 16th century, the Inca Empire was at its height, ruling over perhaps 10 million people. Yet within a few decades, it collapsed under the weight of foreign invasion. The arrival of Spanish conquistadors, led by Francisco Pizarro in 1532, coincided with internal crisis.

A devastating smallpox epidemic had swept through the Andes, killing the Inca emperor Huayna Capac and many nobles. His sons, Atahualpa and Huáscar, plunged the empire into a brutal civil war. When Pizarro captured Atahualpa at Cajamarca, the Incas were weakened, divided, and vulnerable. Despite Atahualpa’s ransom of a room filled with gold and silver, he was executed.

The Spanish, with their steel weapons, horses, firearms, and ruthless tactics, gradually dismantled Inca power. Cusco fell in 1533, and although resistance continued for decades, the empire never recovered. What had taken centuries to build unraveled in the face of disease, betrayal, and conquest.

The Legacy of the Inca

Though the empire fell, the Inca legacy endures. Their roads, terraces, and cities remain, testifying to their genius. Their agricultural practices still sustain Andean communities, and their traditions of music, weaving, and festivals continue to shape cultural identity. Quechua, the language of the Incas, is still spoken by millions across South America.

Modern archaeology and anthropology continue to uncover the richness of Inca civilization. Sites like Machu Picchu inspire awe worldwide, while quipus challenge our understanding of information systems. The Incas remind us that civilization can thrive without wheels, money, or writing, by harnessing cooperation, ingenuity, and respect for nature.

Conclusion: Builders of the Andes

The Inca Empire was a civilization of visionaries—builders who turned mountains into farms, valleys into cities, and roads into lifelines stretching across continents. They embodied a deep relationship with the land, creating a society that balanced human ambition with ecological awareness.

Their story is not only one of conquest and fall but of endurance. The spirit of the Incas lives on in the Andes, in the people who still honor their traditions, and in the stones of cities that have defied centuries of time.

To remember the Incas is to remember that human potential is not limited by tools or technology but driven by imagination, community, and faith in something greater than oneself. They were, truly, the builders of the Andes—and their legacy continues to echo among the mountains they once called home.