Long before the rise of cities or civilization—before agriculture, before myth, before even language as we know it—humans walked the shores of a lake in what is now southern Greece. They were not yet Homo sapiens, but their minds were sharp, their hands skilled, and their survival depended on both. In the basin of Megalopolis, about 430,000 years ago, they knelt beside a fallen giant: an extinct straight-tusked elephant, Palaeoloxodon antiquus.

What they left behind—stone tools, butchered bones, and a record etched in soil—has now revealed itself in the form of one of the most extraordinary archaeological discoveries in Europe’s prehistoric record.

A new study, led by the Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Paleoenvironment at the University of Tübingen and published in the journal PLOS ONE, dives deep into the ancient world of Marathousa 1. This site, an open-air location in the heart of Greece’s Peloponnese, provides rare and striking evidence of complex human behavior during the Middle Pleistocene—nearly half a million years ago.

The Elephant in the Soil

At the heart of the discovery are the remains of Palaeoloxodon antiquus, a now-extinct elephant species that once roamed Europe’s forests. Its bones were found alongside an abundance of stone tools—clear signs that the animal had not died in isolation. It had been dismembered and processed by hominins.

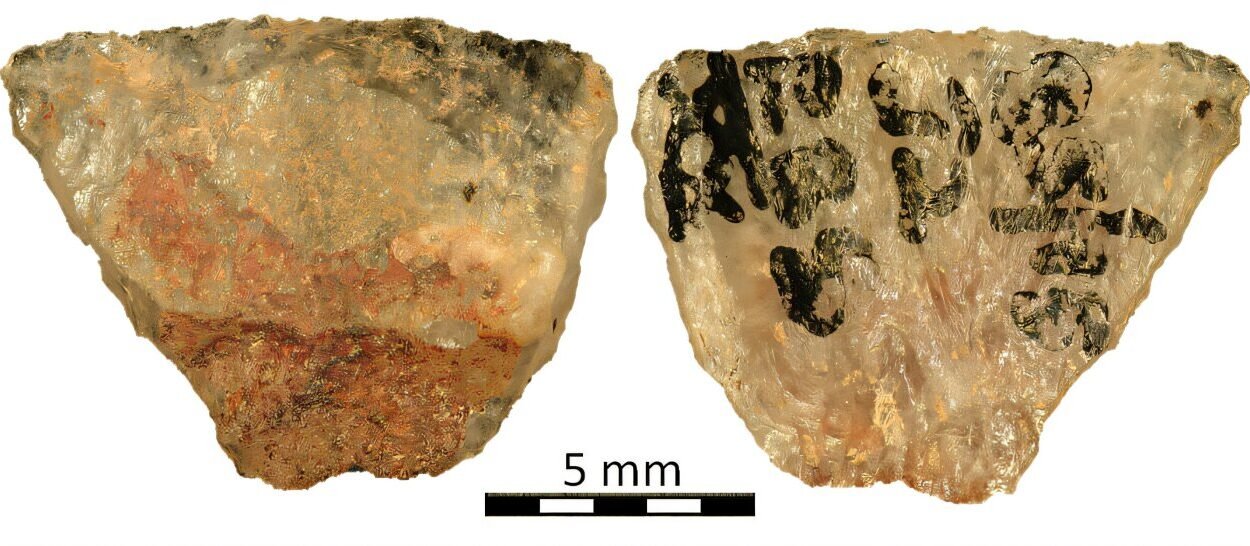

The bones bore distinct cut marks and impact scars, physical proof that early humans used stone implements to break down the massive body of the animal. This activity is not just a footnote in prehistory; it is a rare, direct link between human action and survival strategy, preserved in fossilized form.

Professor Katerina Harvati, a researcher from the Senckenberg Center and a co-author of the study, emphasizes the importance of these markings: “The bones of the large animal fauna show signs of cutting and impact marks—clear evidence of the dismembering and processing of the animals by humans. The site therefore provides important testimony to the hominin way of life in the Middle Pleistocene.”

The Puzzle of the Tools

The study’s lead author, Dalila De Caro—a doctoral candidate in Paleoanthropology at the University of Tübingen—led the analysis of hundreds of stone tools recovered from the site. These tools were not crude, accidental flakes but the products of deliberate craftsmanship, made using more than one technique depending on the tool’s purpose and the properties of the stone.

The hominins at Marathousa 1 used both freehand percussion and a method known as bipolar technique. In the latter, the stone core was placed on a hard surface and struck from above—allowing early humans to maximize their use of even small or difficult pieces of stone. These approaches reveal a flexibility in thinking and problem-solving that pushes back against the outdated image of early humans as simple or primitive.

“Our results show that 430,000 years ago, people combined different tool-making techniques,” says De Caro. “Freehand striking was mainly used to create small, sharp-edged flakes, while the ‘bipolar technique’ was applied to make the most efficient use of the raw material.”

A Landscape of Survival

Why here? Why Marathousa?

To understand that, the researchers looked not only at the tools and bones, but also at the environment. The Megalopolis Basin would have been a haven for prehistoric humans—a water-rich landscape surrounded by stone resources and teeming with animals.

“The site’s location provided access to abundant raw materials like radiolarite, limestone, flint, and quartz,” explains De Caro. “This abundance helped shape the behaviors we’re observing. These hominins weren’t just surviving—they were adapting, experimenting, and thriving in their ecological niche.”

Radiolarite, a hard siliceous rock, was particularly favored. It yielded sharp flakes ideal for slicing flesh or scraping hide. These tiny chips, known as microliths, were once assumed to be signs of technological simplicity. But the findings from Marathousa 1 flip that assumption on its head.

Microliths with a Message

Experiments conducted by the research team confirmed that the small radiolarite flakes recovered from the site were highly efficient at cutting through tough animal tissue. Some were even further modified into specialized tools—scrapers, drills, and serrated implements. Far from being evidence of a crude lifestyle, these tools show advanced planning and deep familiarity with raw materials.

“Small tools are not a sign of simplistic technology,” says Dr. Vangelis Tourloukis, a co-author of the study. “On the contrary, they reflect a well-thought-out adaptation to the requirements of the respective environment.”

This level of adaptation speaks volumes about the ingenuity of early humans. Their technology wasn’t just functional—it was strategic. They exploited the full potential of every stone and bone, responding to their environment with creativity and skill.

A Unique Site in Southern Europe

What makes Marathousa 1 so extraordinary is its context. Sites of this age with such clear evidence of human-animal interaction are incredibly rare in southern Europe. Most archaeological finds from the Middle Pleistocene are either heavily eroded or limited in scope. Here, however, we have an intact landscape, filled with clues.

“This is the currently oldest known archaeological site in Greece,” says De Caro. “It offers a rare opportunity to study human behavior in southern Europe during the Middle Pleistocene.”

The collaboration between Greek and German institutions brought together experts in stone tool analysis, paleoenvironmental reconstruction, and experimental archaeology, resulting in a detailed reconstruction of life as it might have been nearly half a million years ago.

More Than Survival—A Story of Strategy

The key insight from Marathousa 1 is not just that early humans butchered elephants. It’s that they did so with planning, foresight, and an intelligent approach to their surroundings. Their choices of raw materials, their manufacturing methods, and their proximity to water and animals all speak of a sophisticated understanding of their world.

The site paints a portrait of early humans not as brutes battling nature, but as thoughtful agents actively shaping their environment.

“This clearly demonstrates that the dismemberment of animal carcasses was one of the most important activities of the people living on the shores of the prehistoric lake of Megalopolis,” says Tourloukis. “And the flexibility in the production of the tools required for this purpose shows how well these hominins adapted to their environment.”

The Broader Horizon of Human Evolution

Marathousa 1 is a stepping stone—one that helps scientists trace the arc of human evolution across Europe. The behavior observed here raises larger questions: Were similar tool-making strategies used elsewhere? How did environmental features shape human adaptation across Eurasia? And what other secrets still lie buried beneath the soil of forgotten lakes and riverbeds?

The research team hopes that future excavations will help map the spread and development of such behaviors across time and space.

“We would like to clarify how such behavioral patterns developed in other parts of Eurasia and what role environmental factors played in this,” says De Caro.

A Legacy Written in Stone and Bone

It’s easy to think of the deep past as unknowable. But sites like Marathousa 1 remind us that the distant echoes of human life can still be heard—through a chipped stone, a cut-marked bone, a tool left by a lakeshore.

In those fragments, we meet ancestors who were inventive, observant, and capable of much more than mere survival. We see ourselves in their adaptability. We inherit their curiosity.

And in a single radiolarite flake, sharp and purposeful, we find the quiet brilliance of a forgotten moment—when ancient hands turned nature into possibility.

Reference: Dalila De Caro et al, Small flakes for sharp needs: Technological behaviour in the Lower Palaeolithic site of Marathousa 1, Greece, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0324958