Human history, as we know it, has always been a story built on shifting sands. For centuries, archaeologists, historians, and anthropologists believed they had mapped the basic contours of our past—an arc that stretched from primitive hunter-gatherers to the first cities, from the domestication of plants and animals to the rise of writing, war, and civilization.

But what if that timeline is incomplete? What if entire chapters are missing—buried under sediments, lost to fire, or simply too strange to fit the narrative we’ve created? In recent years, astonishing discoveries from remote deserts, frozen tundras, submerged coastlines, and even within our own DNA have begun to shake the foundations of what we thought we knew.

Each find tells a whispering truth: the story of humanity may be far older, more complex, and more surprising than we ever imagined.

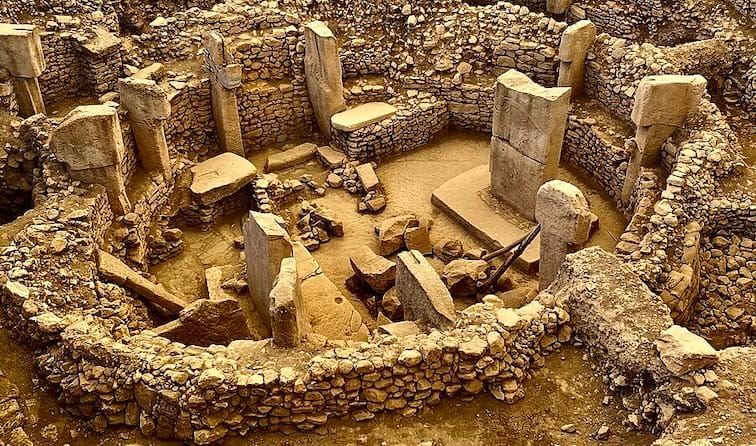

Göbekli Tepe and the Temples Before Time

Perched on a hill in southeastern Turkey lies a site that shattered conventional wisdom almost overnight. Discovered in the 1990s but only recently fully excavated, Göbekli Tepe is now believed to be over 11,000 years old—predating Stonehenge by 6,000 years and the Egyptian pyramids by 7,000. This is not merely an old structure. It is a ceremonial temple complex, with T-shaped limestone pillars weighing tons, carved with intricate reliefs of animals, abstract symbols, and possible proto-writing.

What truly stunned archaeologists wasn’t just the age or scale of Göbekli Tepe—it was the implication. The site was built by hunter-gatherers before the rise of agriculture. It reverses the traditional model, where organized farming societies were thought to have made large, settled religious architecture possible. Here, it seems, religion came first—perhaps even causing the shift toward agriculture. People may have come together to build this sacred place and only later figured out how to farm to support their gathering.

It asks a dangerous question: what else have we overlooked, simply because we weren’t willing to believe it could exist?

The Ancient Footprints That Shouldn’t Be There

In 2021, a quiet announcement from White Sands National Park in New Mexico rocked the world of anthropology. Researchers discovered fossilized human footprints embedded in ancient lakebed sediments. The dating method, based on seeds embedded in the same layer, placed the prints at around 21,000 to 23,000 years old.

This sent shockwaves through the academic community. For decades, the dominant theory was that humans first entered the Americas no earlier than 13,000 years ago, via the Bering land bridge. These footprints, however, suggested people had already been living in North America thousands of years before the supposed “Clovis First” migration.

The implications are staggering. If accurate, it means our ancestors reached the New World during the peak of the Ice Age, adapting to an environment far more hostile than previously imagined. It forces scientists to re-evaluate the origins and routes of human migration and the technologies they used to survive.

What’s more, it suggests something even deeper: that our ability to thrive in extremes, to explore and expand into new worlds, is far older than modern archaeology had ever guessed.

The Rise of Lost Civilizations Beneath the Sea

The sea has always been both cradle and grave for human civilization. As sea levels rose at the end of the last Ice Age, entire coastal settlements disappeared beneath the waves. For decades, these lost worlds were considered inaccessible. But that is beginning to change.

In the Indian Gulf of Khambhat, sonar scans have revealed what may be the submerged remains of a city predating the Indus Valley civilization by thousands of years. In the Mediterranean, underwater archaeologists have uncovered roads, buildings, and harbor systems off the coasts of Egypt, Greece, and Israel. And around Doggerland—the now-submerged landmass that once connected Britain to mainland Europe—researchers have found traces of hunting camps and even worked stone tools.

All of these suggest that civilization may not have begun in a few river valleys, as once believed, but in dozens of scattered locations—many of which now lie beneath oceans.

This raises a thrilling possibility: could the first complex human societies have arisen during the Ice Age, only to vanish beneath rising seas, leaving behind barely a trace? If so, the story of civilization doesn’t begin at Sumer or Egypt, but in places we’re only just beginning to rediscover.

The Hidden Histories in Our DNA

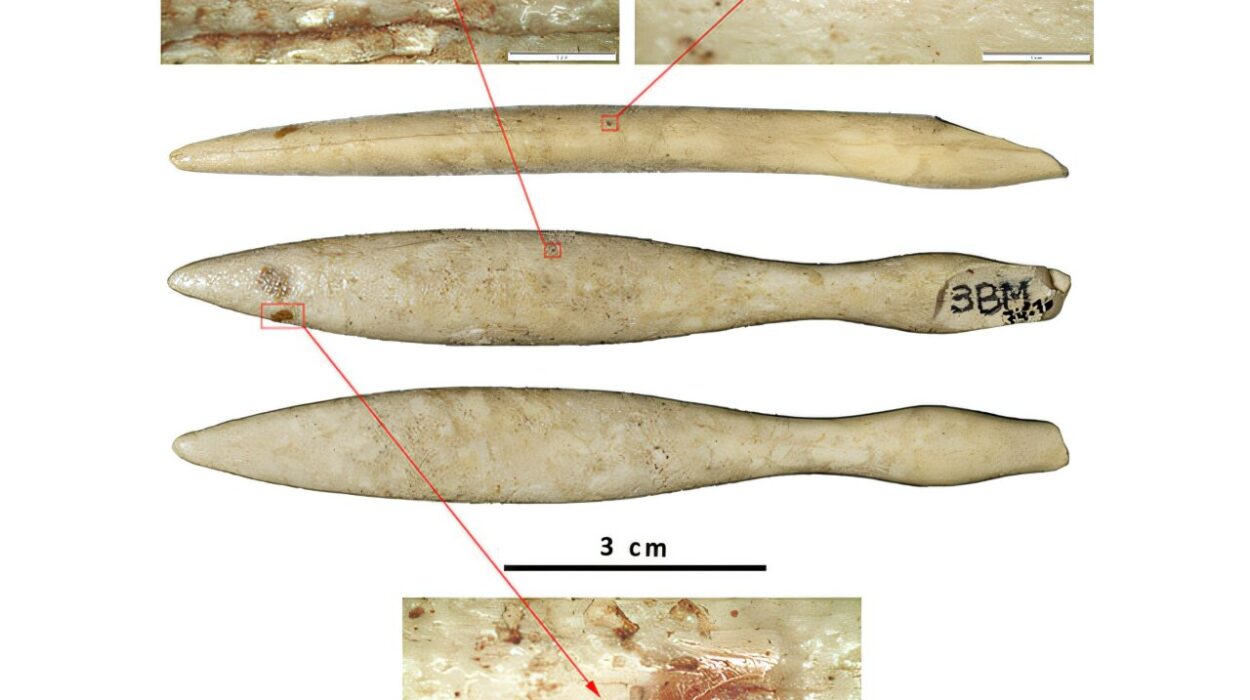

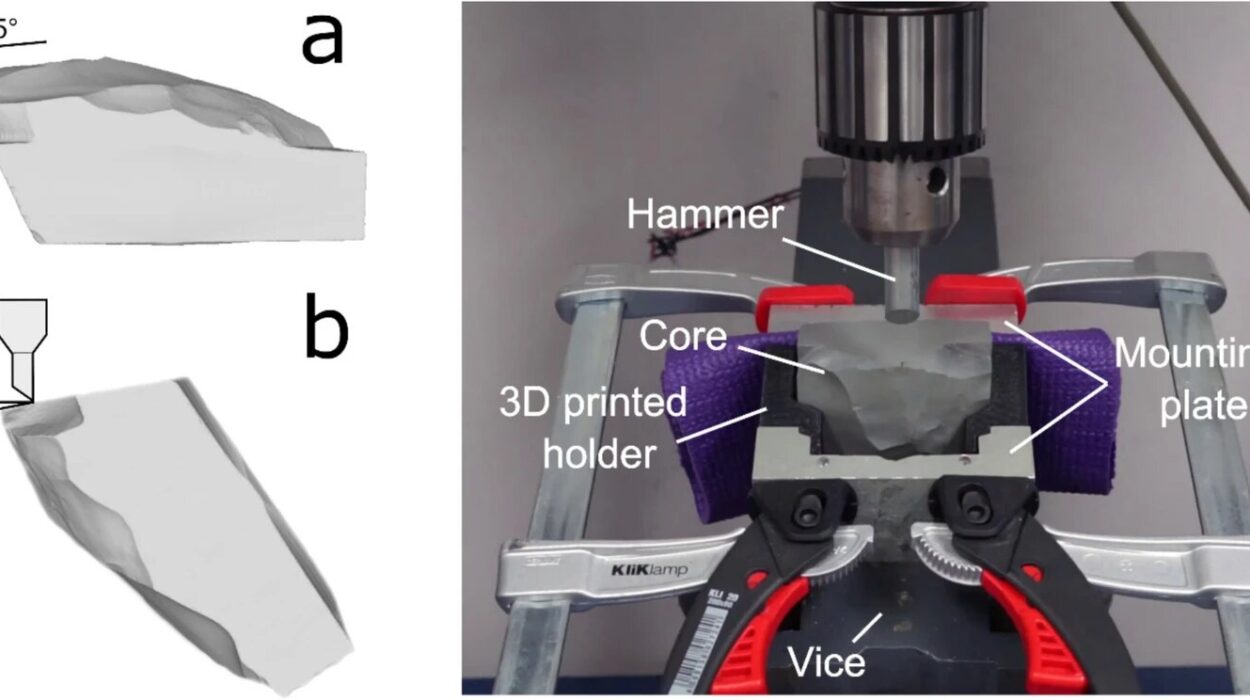

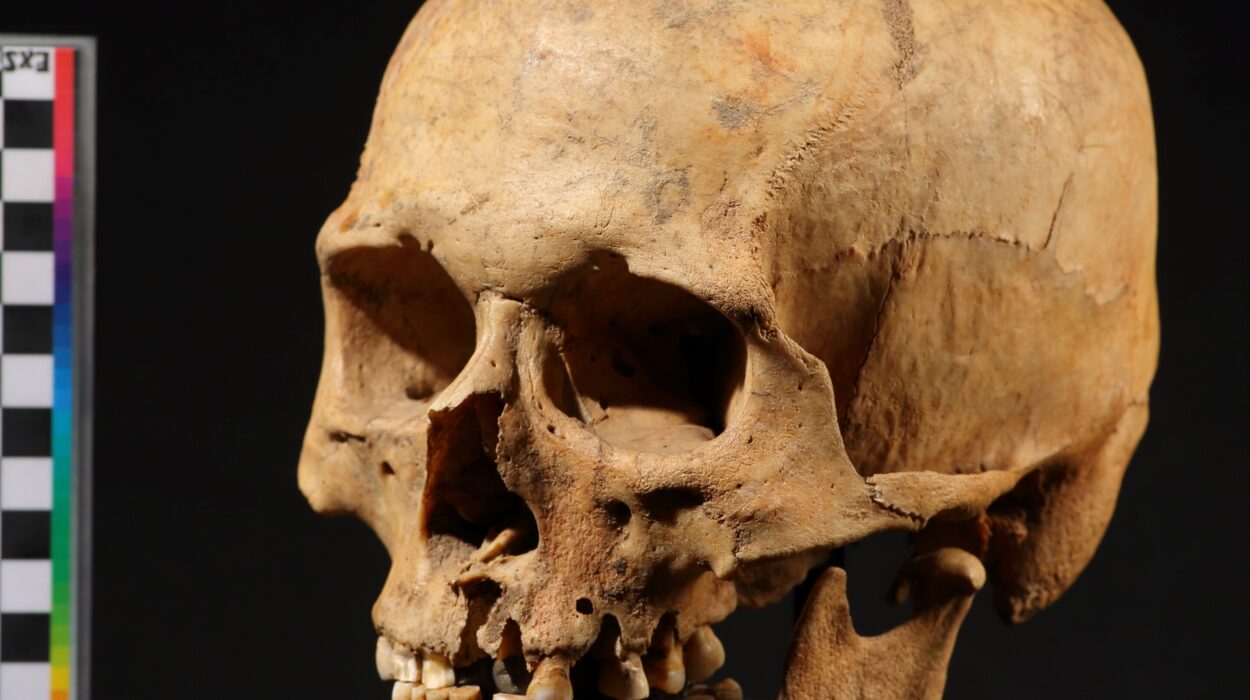

Our bones remember what our books forget. In the last decade, ancient DNA analysis has turned the study of human history inside out. From tiny fragments of bone and teeth, scientists are reconstructing epic migrations, lost peoples, and forgotten ancestors.

One of the most groundbreaking revelations came with the discovery of the Denisovans. This mysterious hominin species, identified from a single finger bone found in a Siberian cave, was previously unknown to science. Yet traces of Denisovan DNA live on in millions of modern humans, especially in Melanesian and Southeast Asian populations.

Similarly, genetic studies have revealed that Neanderthals, once thought to be brutish and separate from us, interbred with Homo sapiens repeatedly. Most non-Africans today carry between 1–2% Neanderthal DNA.

Even more astonishing are hints of “ghost populations”—groups that left no known fossils but whose DNA appears in the genomes of modern humans. These discoveries suggest that the story of humanity isn’t one clean line but a tangled braid of species, tribes, and genes—intermingling, splitting, and recombining over hundreds of thousands of years.

In essence, we are not the last of one kind but the product of many.

Rewriting Prehistory with Fire and Stars

Recent findings suggest our ancestors were far more sophisticated than once thought, even in the deep Paleolithic past. In South Africa’s Blombos Cave, archaeologists have discovered ochre patterns etched into stone that may represent the world’s oldest abstract symbols—dated to around 75,000 years ago.

In northern Australia, Aboriginal rock art might be tens of thousands of years old, filled with complex cosmology, astronomy, and myth. Oral traditions passed down over millennia contain references to geological events—like volcanic eruptions or changing coastlines—that happened more than 10,000 years ago. Could memory itself be an ancient technology, preserving history before writing?

In Amazonia, long dismissed as a wild, untouched wilderness, lidar (laser imaging) has revealed vast city-like structures—grids of roads, canals, and geometric mounds—once hidden under dense jungle. These discoveries suggest that far from being primitive, many Indigenous peoples were engineers of landscapes, cultivating entire ecosystems in sustainable ways.

Even cave paintings, once seen as simple animal depictions, are being re-evaluated. Some may contain early lunar calendars, stellar maps, or visual expressions of altered states of consciousness.

It’s as if we are waking up to an uncomfortable truth: that the people of the deep past were not merely surviving, but thinking, dreaming, creating, and understanding the world in ways we are only beginning to comprehend.

The Mystery of the Megalith Builders

Massive stone monuments dot the landscapes of nearly every continent—from the moai of Easter Island to the dolmens of Korea, from the stone circles of Senegal to the pyramids of Egypt and Mesoamerica. For years, these structures were treated as local phenomena, products of individual cultures.

But increasingly, researchers are noting striking similarities in design, orientation, and symbolism. Many align with solstices or equinoxes. Others echo geometric principles found across the globe.

Why were early humans so obsessed with moving stones weighing tens or even hundreds of tons? How did they do it, sometimes without the wheel, metal tools, or draft animals?

Some scholars now suggest that megalith building may have been a global tradition—a kind of shared cultural blueprint passed through migration or ancient contact. While this doesn’t require theories of lost continents or extraterrestrials, it does ask us to reconsider how knowledge once spread.

Could the world have been more connected in deep antiquity than we imagine?

Buried Cities and the Shadows of Forgotten States

In Cambodia, laser scans have revealed that the great city of Angkor was just the visible tip of an enormous urban sprawl—complete with highways, reservoirs, and suburbs—much of it still hidden under forest. Similarly, in Guatemala, lidar surveys have shown that the Mayan civilization was vastly more interconnected than previously believed, with tens of thousands of buildings, roads, and pyramids still buried beneath jungle.

And then there are the truly enigmatic sites: Nan Madol, built on artificial islands in the Pacific. The subterranean labyrinths of Cappadocia in Turkey. The ancient, now-sunken city of Dwarka in India’s coastal shallows. All of them hint at civilizations that operated with levels of complexity—and perhaps even cosmopolitanism—that challenge our assumptions about early states.

These places weren’t just isolated outposts. They were vibrant centers of politics, trade, spirituality, and science. Some were abandoned due to climate shifts, wars, or disease. Others fell into myth and legend.

But they all whisper the same haunting idea: that history remembers what survives, not necessarily what mattered most.

A Past That Refuses to Stay Buried

The pace of discovery is accelerating. Satellites scan the Earth for anomalies. Geneticists decode genomes from teeth no bigger than a thumbnail. AI tools now analyze archaeological data for patterns no human could ever see. And still, the picture remains incomplete.

Every discovery seems to push the timeline of human complexity back. Every new tool raises new questions. Were there civilizations before civilization? Have entire eras of human achievement been lost, not because they were unimportant, but because they left behind no monuments we recognized as such?

Some of these questions make traditional historians uneasy. They feel too speculative, too risky. But science thrives on risk—on asking uncomfortable questions, on challenging dogma, on allowing the evidence to speak, even when it whispers things we aren’t ready to hear.

The Echoes That Bind Us

In the end, these discoveries don’t just rewrite history—they rewrite us. They make us more humble, more curious. They force us to look at Indigenous traditions, ancient mythologies, and oral histories not as quaint relics, but as repositories of memory and truth. They invite us to imagine a world where knowledge doesn’t always leave a digital fingerprint, a stone monument, or a written scroll—but may still endure.

They ask us to look around at our own world and wonder: what will future archaeologists say about us? What truths will they uncover beneath the concrete and glass of our cities? What stories will survive us?

The deeper we dig, the more we find that the line between past and present, myth and fact, known and unknown, is not a line at all—but a bridge. A shimmering thread of curiosity stretching across time.

And as we walk that bridge, it becomes clear: the history of humanity is not a finished book, but a living manuscript—still being written, still being discovered, and still holding secrets that could change everything we think we know.