Few images from history capture the imagination with as much intensity as that of the Aztec priest, standing atop a towering pyramid, lifting a blade of obsidian, and offering a human heart to the sun. To modern eyes, the practice of human sacrifice in the Aztec civilization can seem brutal, alien, and incomprehensible. Yet to the Aztecs themselves, it was not cruelty for cruelty’s sake, but a sacred duty, an act that bound their society to the cosmos.

For the Aztecs, sacrifice was not only a ritual of religion—it was the very pulse of existence. It was the heartbeat of their empire, a bridge between the earthly and the divine, between human mortality and cosmic eternity. To understand why the Aztecs devoted themselves so fervently to this practice, one must step into their worldview, where gods demanded nourishment, the sun required strength to rise, and blood was the most precious currency of life.

The Aztec Worldview: Life Through Death

The Aztecs, or Mexica as they called themselves, were heirs to centuries of Mesoamerican culture. By the 14th century, they had risen from nomadic outsiders to rulers of a vast empire in the Valley of Mexico. Their religion, like that of their predecessors, was deeply entwined with the cycles of nature: the rising and setting of the sun, the planting and harvesting of maize, the alternation of life and death.

At the heart of their cosmology lay the idea that the universe was fragile, precarious, and in constant need of renewal. The Aztecs believed that the gods themselves had sacrificed in order to create the world. According to their myths, the current era—the Fifth Sun—was born when the gods gathered at Teotihuacan to decide who would give their life to become the sun. The humble god Nanahuatzin threw himself into the fire, emerging as the radiant sun, but he lacked the strength to move across the sky. Only by receiving the blood and hearts of gods could the sun begin its eternal journey.

This myth was not mere story; it was the foundation of Aztec ritual. If the gods had sacrificed themselves for humanity, then humanity must, in turn, sacrifice for the gods. Without these offerings, the sun might falter, the rains might cease, the crops might wither, and the world might collapse into darkness. Life was a gift that could only be repaid with life.

The Sacred Economy of Blood

Blood was seen as the essence of vitality, the sacred fluid that sustained gods and humans alike. In the Aztec language, Nahuatl, the term chalchíhuatl was used to describe human blood, considered “precious water.” Hearts, beating and warm, were called tona, or the “seat of the soul.” To offer these to the gods was to give them the very force of life.

This belief created a ritual economy where blood was the most valuable tribute. Unlike material wealth, which could be hoarded, blood had to be continually renewed. Sacrifice was therefore not an occasional event but a constant necessity, woven into the rhythm of Aztec life.

Every major festival, every temple dedication, and every victory in battle was an opportunity for sacrifice. The grandeur of Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, was matched only by the scale of its ritual life, where thousands of captives might be offered during great ceremonies. To the Aztecs, these acts were not gruesome displays but sacred obligations, essential to the survival of the cosmos.

The Rituals of Sacrifice

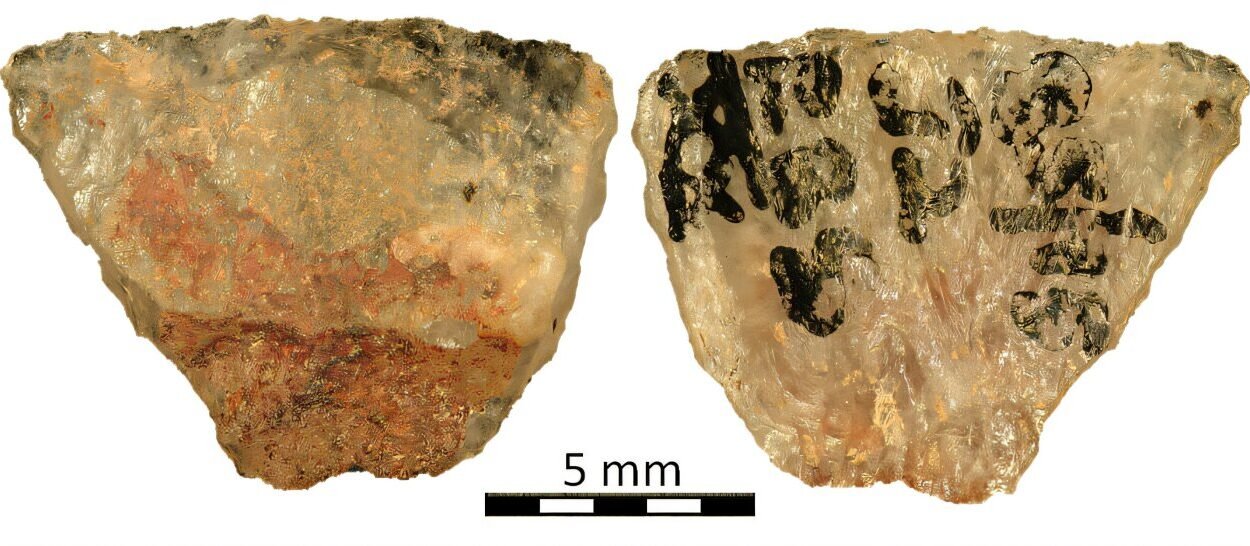

Human sacrifice took many forms in Aztec ritual, each associated with specific gods, festivals, and symbolic meanings. The most iconic was the offering of a heart on the summit of the templo mayor, the great twin pyramid in the heart of Tenochtitlan. There, priests would lay the victim on a stone altar, open the chest with an obsidian blade, and lift the heart skyward to nourish the gods. The body, still warm, might be cast down the steps of the pyramid, a dramatic return to the earth.

But sacrifice extended beyond this central ritual. Some victims were decapitated, imitating the agricultural cycle of harvest. Others were shot with arrows, symbolizing the piercing rays of the sun. In gladiatorial-style sacrifices, warriors were tied and forced to fight against heavily armed opponents, their doomed struggle a reenactment of cosmic battles. Still others were drowned, burned, or flayed, their deaths tailored to the nature of the deity being honored.

For instance, Tlaloc, the god of rain and fertility, was believed to favor the tears of children. In festivals dedicated to him, children were sacrificed, and their tears were thought to bring rain. For Xipe Totec, the “Flayed Lord” associated with renewal and agriculture, victims were skinned, their flesh worn by priests to symbolize the shedding of old skin and the rebirth of the earth. Each ritual was a performance rich in symbolism, echoing the cycles of nature and myth.

Warriors, Captives, and the “Flower Wars”

Not everyone was destined for sacrifice. Victims were most often war captives, taken in battles specifically fought to supply lives for ritual. These conflicts, known as “flower wars” (xochiyaoyotl), were arranged between city-states not for territorial conquest but for the capture of prisoners. Warriors who brought back captives for sacrifice gained prestige, while those captured themselves fulfilled the ultimate honor of serving the gods through death.

The flower wars reveal the intricate relationship between warfare and religion in Aztec society. War was not only about power or expansion; it was also a sacred duty to feed the gods. Young men trained as warriors knew that their fate could be either to capture or to be captured, to kill or to be sacrificed. Both roles were valorized, for in either case, they became part of the cosmic drama.

The Victims: Honored or Doomed?

How did the victims themselves view their fate? This question is difficult to answer, as most of the surviving records come from Spanish chroniclers who described sacrifice through the lens of shock and condemnation. Yet some sources suggest that sacrifice was not always regarded as punishment, but as a pathway to honor.

Those sacrificed were believed to accompany the sun on its journey through the sky. Warriors who died in battle or on the altar, and women who died in childbirth, were granted special afterlives, their souls transformed into hummingbirds or butterflies, symbols of vitality and renewal. To be sacrificed could therefore be seen not as annihilation, but as transcendence—a chance to live on in service to the gods.

Still, it is likely that the experience was far from serene for most captives. Accounts tell of struggles, cries, and resistance, reminding us that beneath the symbolic grandeur, these were real human lives ended in ritual bloodshed. The duality of honor and horror defines the Aztec practice, both exalting and extinguishing human existence.

The Scale of Sacrifice

One of the most debated aspects of Aztec human sacrifice is its scale. Spanish conquistadors, eager to depict the Aztecs as barbaric, claimed that tens of thousands were sacrificed in single ceremonies. Hernán Cortés and Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote of temples reeking of blood, their steps stained red.

Archaeological evidence supports the prevalence of sacrifice but suggests more complexity than the conquistadors’ dramatic numbers. Excavations at the Templo Mayor in Mexico City have uncovered remains of sacrificed individuals, including skull racks known as tzompantli. These racks, where skulls were displayed, confirm the ritual display of human remains. Estimates of annual sacrifices vary, ranging from several thousand to perhaps as many as twenty thousand in particularly grand ceremonies.

What is certain is that sacrifice was not a marginal practice—it was central to Aztec state religion. The empire’s power, wealth, and military organization were all tied to the supply of captives for the gods.

Spanish Encounters and the End of Ritual

When the Spanish arrived in 1519, they were horrified by what they saw. To the Catholic worldview, human sacrifice was an abomination, evidence of satanic corruption. The conquistadors used the practice as justification for conquest, portraying themselves as saviors who brought an end to barbarity.

The fall of Tenochtitlan in 1521 marked not only the collapse of the Aztec Empire but also the suppression of its rituals. Temples were destroyed, idols smashed, and sacrifices outlawed. Yet the memory of these practices endured, recorded in both Spanish chronicles and Indigenous codices. The image of Aztec human sacrifice became a powerful symbol, alternately demonized, sensationalized, and romanticized in centuries that followed.

Rethinking Sacrifice: Beyond Horror

Today, historians and archaeologists strive to understand Aztec sacrifice not simply as cruelty, but as part of a complex worldview. It was a system of belief in which gods and humans were bound in mutual obligation, where blood was both debt and gift. While the practice shocks modern sensibilities, to dismiss it as mere savagery is to miss the profound religious, social, and political significance it held.

Sacrifice reinforced the power of the state, demonstrated the might of the gods, and unified society in shared rituals. It was both a religious necessity and a tool of empire. It created awe, fear, and cohesion in equal measure. In the grandeur of ceremony and the gravity of death, the Aztecs enacted their vision of a universe balanced on the edge of chaos, sustained by the lifeblood of humanity.

The Legacy of Aztec Sacrifice

The legacy of Aztec human sacrifice endures, haunting and fascinating the modern imagination. It raises profound questions about the nature of belief, the meaning of life and death, and the lengths to which societies will go to sustain their visions of the cosmos.

For the Aztecs, sacrifice was not senseless violence but sacred necessity. It was their way of keeping the sun rising, the rains falling, and the world alive. Yet in their devotion, they also revealed the paradox of humanity: our capacity for faith and meaning, and our willingness to spill blood in their service.

To study Aztec human sacrifice is not only to confront the past but to reflect on the present. It forces us to ask: what do we sacrifice today? What rituals, wars, or beliefs do we still justify in the name of survival, order, or faith? The Aztecs may be gone, but their story endures as a mirror—showing us the power and peril of human conviction.

Conclusion: Blood, Faith, and the Fragile Cosmos

Human sacrifice in the Aztec civilization was both terrible and transcendent. It was an act that united myth and reality, symbol and flesh. It was a drama played on the towering steps of pyramids, watched by thousands, and believed to sustain the very order of the cosmos.

To modern eyes, it may be repellent, but to the Aztecs, it was the highest form of devotion, a sacred offering that repaid the gods for their original gift of life. In blood and in death, they found meaning, power, and connection to forces greater than themselves.

The story of Aztec sacrifice is not only about the past—it is about the enduring human quest to understand our place in the universe, to seek order in chaos, and to give meaning to life and death. It is a reminder that belief can inspire greatness and cruelty, beauty and horror, faith and fear.

In the end, the Aztecs sacrificed not merely human lives but their own certainty that the universe could endure without such offerings. Their rituals were their answer to the fragility of existence, their way of holding the cosmos together. And though the practice is long gone, the questions it raises remain timeless—about life, death, and the costs of faith in a fragile world.