The Maya Civilization is often remembered for its monumental temples and its mysterious societal collapse. But beneath the stones lay something even more astonishing: a mind that looked beyond the present and reached into the mechanics of the sky. Long before telescopes, equations, and satellites, the Maya tracked the heavens with a precision that still startles modern scientists. They built numbers out of darkness and time, made of cycles instead of machines. Their records were not casual notations; they were instruments of prediction.

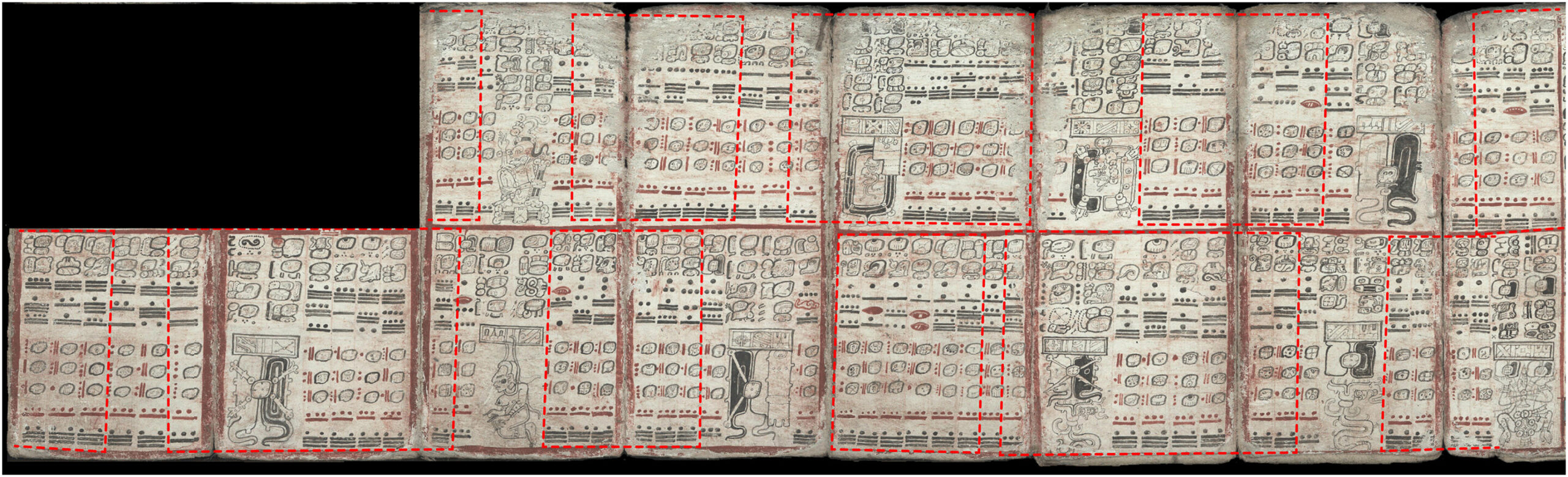

Among the surviving remnants of this extraordinary intellectual world is the Dresden Codex — a bark-paper manuscript whose faded red and black marks once served as navigational tools for priests and astronomers. Within it lies an enigmatic table spanning 405 lunar months. Scholars knew it had something to do with eclipses, but not exactly how or why it worked. New research has finally reconstructed the logic that powered this ancient algorithm, and it reveals a level of structural ingenuity that rivals modern computational strategies.

The Eclipse Table Was Not What Scientists Imagined

For years, the dominant assumption was that the 405-month span was engineered strictly for the purpose of predicting eclipses. Eclipses mattered to the Maya for cosmological and ritual reasons — they were events heavy with meaning. Yet the new paper in Science Advances finds that the original purpose of the table was not eclipse prediction as such. Instead, its architecture was derived from a more fundamental need: to align the lunar cycle with the 260-day divinatory calendar that governed ritual life, prophecy, agriculture, and royal power.

The length of the table — 11,960 days — is not arbitrary. It is exactly forty-six repetitions of the sacred 260-day count. That harmony is far tighter than any eclipse-related cycle. The conclusion is that eclipse prediction was not the origin of the table but a by-product that emerged naturally from the lunar-calendar structure. Solar eclipses appear at specific phases of lunar cycles, so once the Maya achieved calendar–lunar commensuration, they could use it as a reference grid to anticipate when the moon would be in an eclipse-enabling position.

The Maya, in short, predicted the future sky by beginning not with rare spectacular events but with the steady heartbeat of the moon and the ritual calendar through which they interpreted the world.

A Brain Made of Cycles and Corrections

Precision over centuries is not trivial. Astronomical cycles drift. Small errors accumulate. A model that is correct in one generation may be wrong two generations later. Previous scholars thought the Maya compensated by replacing old tables with new ones whenever precision decayed. The new study overturns that assumption as well. Instead of discarding a table, the Maya overlapped them.

Before one 405-month run finished, another table would begin — not at its beginning but at a strategic internal offset of 223 or 358 months. These offsets were not guesses; they were corrections engineered to cancel accumulated error. In mathematics, this is a kind of modular restart — a reboot not from zero but from a corrective remainder. This approach allowed the Dresden Codex system to remain accurate for more than seven centuries, successfully tracking every eclipse visible to the Maya between 350 and 1150 CE.

What the researchers reconstructed is not just an artifact but an algorithm — an indexical machine that refreshes itself without erasing its past.

Astronomy, but Also Philosophy

The Maya were not doing astronomy for entertainment or curiosity alone. Their entire intellectual universe was cyclic. History, weather, kingship, ritual authority — all were embedded in recurring rhythms. Eclipses were not isolated spectacles but nodes within a cosmic graph of meaning. To predict an eclipse was also to place it within a moral and ritual schedule.

What makes the new research remarkable is that it shows the Maya did not need to develop a separate eclipse-specific computing system. They extended the logic of a calendar that already unified human and celestial time. The eclipse table is therefore a spiritual instrument and a mathematical one at once. It is a rare case in which the pragmatic and the metaphysical share the same spine.

An Ancient Intelligence Still Astonishing

Modern science is used to thinking of ancient astronomy as clever approximation. The Dresden Codex research demands a different tone. The Maya solved a multidimensional alignment problem — lunar phase, eclipse periodicity, and ritual count — without mechanical aids, without algebraic notation, without optics, and then built in a mechanism for maintaining global accuracy across centuries.

The codex is not merely evidence of observation. It is evidence of abstraction. It shows that a civilization without silicon could still construct long-horizon predictive models that behave like self-correcting software. In that sense, the Dresden Codex is not a memory of the past but a map of how far disciplined thinking can travel even under constraints.

The new study does not close a mystery so much as refine our respect. The Maya did not watch the sky passively — they domesticated time. Their calendars were engines of foresight, and their eclipse table is proof that humans have been forecasting the future of nature not for hundreds of years, but for thousands.

More information: John Justeson et al, The design and reconstructible history of the Mayan eclipse table of the Dresden Codex, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adt9039