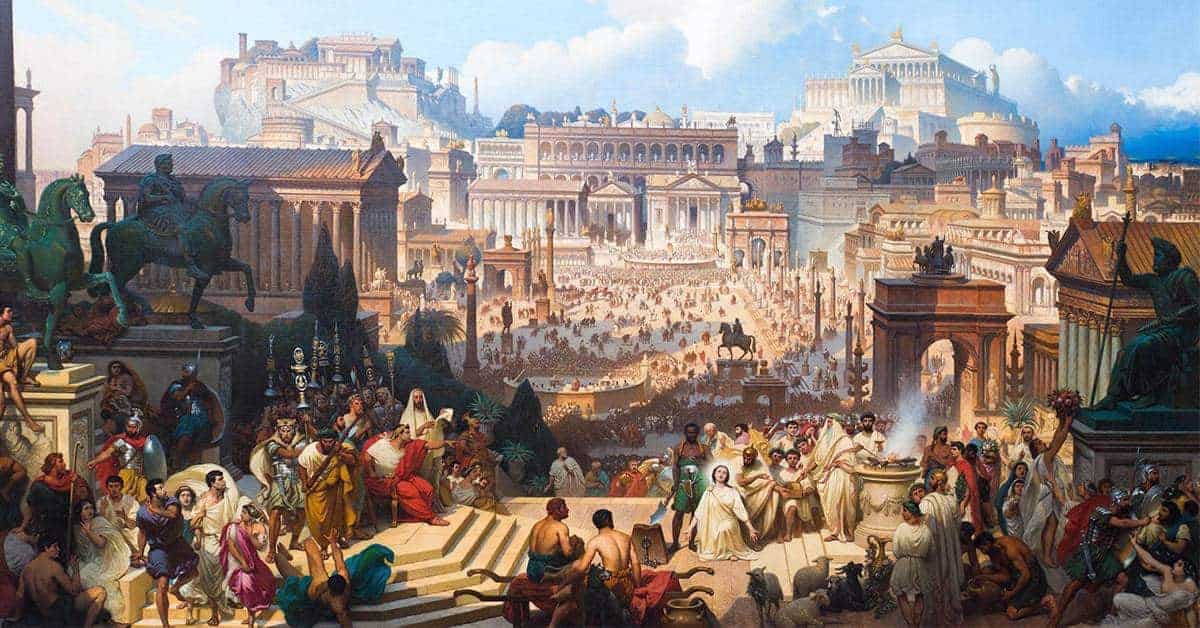

In the annals of history, few figures loom as large or as luminous as Alexander the Great. To speak his name is to summon images of conquest and ambition, of armies marching across deserts and mountains, of cities rising from barren landscapes, and of a young man whose life burned with such intensity that even two millennia later, his legend refuses to fade.

Alexander was not just a king, not merely a conqueror. He was a visionary who sought to unite the known world under one banner, a dreamer who imagined a fusion of cultures, and a warrior who dared to chase glory to the ends of the earth. His life was astonishingly brief—he died at only thirty-two—but in that short span, he reshaped the ancient world, leaving behind an empire that stretched from Greece to Egypt, from the Persian heartlands to the edge of India.

To call him “Great” is no exaggeration. His conquests were unparalleled, his charisma unmatched, his ambition unquenchable. Yet, he was also a man of contradictions: merciful and ruthless, visionary and reckless, brilliant and flawed. To understand Alexander is to confront the duality of human greatness—the capacity to inspire and to destroy, to dream beyond limits and to pay the price of ambition.

The Roots of Greatness: Childhood in Macedonia

Alexander was born in 356 BCE in Pella, the capital of Macedonia, a kingdom on the northern fringes of the Greek world. His father, King Philip II, was a formidable ruler and military innovator who transformed Macedonia from a backwater into a rising power. His mother, Olympias, was a woman of fiery spirit and unshakable will, deeply devoted to her son and determined to see him achieve greatness.

From the beginning, Alexander’s life was steeped in stories of heroes and gods. According to legend, on the night of his birth, the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus—one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World—was set ablaze, as if the cosmos itself had signaled the arrival of a world-altering figure. Olympias instilled in him a belief in his divine lineage, claiming descent from Achilles, the greatest hero of the Trojan War. Alexander grew up believing that he was destined not just to rule but to transcend the ordinary boundaries of human life.

Education was central to his upbringing. Philip, recognizing his son’s potential, brought in the greatest tutor of the age: Aristotle. Under the philosopher’s guidance, Alexander learned literature, science, philosophy, and politics. He studied Homer’s Iliad with passionate devotion, reportedly keeping a copy with him at all times during his campaigns. From Aristotle, he absorbed an intellectual curiosity that would later fuel his interest in blending cultures, fostering knowledge, and founding cities as centers of learning.

But Alexander was not only a student of ideas—he was a student of war. His father taught him the art of leadership and the discipline of the phalanx, the fearsome Macedonian infantry formation that would become the backbone of his conquests. By his teenage years, Alexander was already commanding troops in battle, displaying a courage and tactical brilliance that inspired loyalty and fear in equal measure.

Inheriting the Throne

In 336 BCE, when Alexander was just twenty, his father Philip was assassinated under murky circumstances. Whether it was a personal vendetta, a political conspiracy, or even (as some whispered) Olympias’s involvement, history never settled the matter. What was certain was that the young prince suddenly found himself thrust into power at a moment of extreme instability.

The throne of Macedonia was not a prize easily held. Enemies circled on all sides—restive Greek city-states in the south, hostile tribes in the north, and the looming shadow of Persia, the greatest empire of the age, to the east. Many doubted Alexander’s ability to rule, dismissing him as too young, too inexperienced. But Alexander silenced his critics with ruthless efficiency. He crushed rebellions, secured the loyalty of his nobles, and marched his armies with decisive swiftness.

Most famously, when the city of Thebes revolted, Alexander responded with overwhelming force. Thebes, a city with a proud history, was razed to the ground, its inhabitants killed or sold into slavery. It was a brutal message: Alexander would not tolerate defiance. Greece was brought under his control, and the stage was set for a far greater ambition.

The Dream of Conquest

From the time he was a boy, Alexander had dreamed of emulating Achilles, of achieving everlasting glory through conquest. But his ambition extended beyond mere heroism. His father Philip had already planned an invasion of Persia, the sprawling empire that dominated Asia and had once tried to subjugate Greece. After Philip’s death, Alexander took up that mantle—not simply to avenge Greece, as propaganda claimed, but to surpass every conqueror who had come before.

In 334 BCE, Alexander crossed the Hellespont (modern-day Dardanelles) into Asia Minor with an army of about 40,000 men. As he stepped onto Asian soil, he is said to have thrown a spear into the ground, declaring it a gift to the gods and a claim to the land. It was a symbolic act, marking the beginning of a campaign that would forever alter the course of history.

The Battles That Defined an Empire

Alexander’s military campaigns are studied to this day for their brilliance, audacity, and innovation. His victories were not merely the result of brute force but of tactical genius, psychological mastery, and relentless energy.

The first major clash came at the Battle of the Granicus River, where Alexander led a daring cavalry charge that routed the Persian forces despite overwhelming odds. This victory opened Asia Minor to him and signaled that the young Macedonian king was a force unlike any the world had seen.

Two years later, at the Battle of Issus (333 BCE), Alexander faced the Persian King Darius III himself. Vastly outnumbered, Alexander’s disciplined phalanx and his decisive leadership broke the Persian lines, forcing Darius to flee the battlefield. The shock of the defeat reverberated across the empire, and Alexander gained control of the Levant and Egypt.

In Egypt, Alexander was welcomed as a liberator. He founded the city of Alexandria, which would become a beacon of culture and knowledge for centuries. At the Oracle of Siwa in the desert, he was proclaimed the son of Zeus-Ammon, further reinforcing his belief in his divine destiny.

The final, decisive confrontation with Persia came in 331 BCE at the Battle of Gaugamela. Darius assembled a massive army, with war elephants, chariots, and troops from across his empire. Yet Alexander’s tactical brilliance once again carried the day. Outmaneuvering Darius and striking at the heart of his forces, Alexander shattered Persian power and claimed the title of King of Kings. The Persian Empire, once the mightiest in the world, lay at his feet.

Marching Beyond Persia

For many rulers, the conquest of Persia would have been the pinnacle of achievement. But for Alexander, it was only the beginning. He pressed eastward, driven by an insatiable hunger for exploration and conquest. He marched through the rugged mountains of Central Asia, battled fierce nomadic tribes, and pushed his army to the limits of endurance.

In India, he faced one of his most formidable challenges at the Battle of the Hydaspes River in 326 BCE. There, King Porus commanded war elephants and fierce warriors. The battle was brutal, fought in rain and mud, but Alexander’s strategy prevailed. Impressed by Porus’s courage, Alexander restored him as a ruler, showing a magnanimity that earned him admiration even among his enemies.

Yet, at the edge of the known world, Alexander’s soldiers finally reached their breaking point. Exhausted, homesick, and fearful of the endless unknown, they refused to march further into India. Reluctantly, Alexander turned back, his dream of reaching the “ends of the earth” unfulfilled.

The Vision of a Unified World

Alexander was not merely a conqueror; he was a builder. Wherever he went, he founded cities—often named Alexandria—that became centers of trade, culture, and learning. These cities spread Greek language, art, and philosophy across his empire, laying the foundation for what historians call the Hellenistic Age.

But Alexander’s vision went further. He sought to blend the cultures of East and West, encouraging intermarriage between his soldiers and local populations, adopting Persian dress and customs, and promoting a sense of unity across his diverse empire. This policy, though controversial among his Macedonian companions, was revolutionary. It foreshadowed ideas of globalization and cultural exchange that still resonate today.

The Fall of a Titan

In 323 BCE, Alexander returned to Babylon, the heart of his empire. Plans were underway for new campaigns, including a conquest of Arabia. But destiny had other designs. In June of that year, Alexander fell suddenly ill—whether from fever, poisoning, or other causes remains one of history’s enduring mysteries. After days of suffering, he died at the age of thirty-two.

His death left the empire in turmoil. Without a clear successor—his son was an infant—his generals carved up the vast territories into rival kingdoms. The unity he had fought to build dissolved, but the cultural legacy endured. Greek language and ideas spread across the Middle East and Asia, influencing art, science, philosophy, and politics for centuries.

The Legacy of Alexander the Great

What makes Alexander truly great is not only the scale of his conquests but the lasting impact of his vision. His empire may have fractured after his death, but the Hellenistic world that followed bore his mark indelibly. Cities like Alexandria in Egypt became hubs of scholarship, home to the legendary Library of Alexandria, where knowledge from across the world was collected. Greek became the lingua franca of trade and diplomacy, shaping the intellectual landscape of the Mediterranean and beyond.

Alexander’s legacy also lived on in myth and legend. In countless cultures, from Europe to the Middle East to South Asia, stories of Alexander blended history and folklore, transforming him into a larger-than-life figure who symbolized both the possibilities and the perils of ambition.

To this day, historians, generals, and dreamers study his campaigns, debate his motives, and marvel at his audacity. He remains both an inspiration and a warning—a man who reached heights few could imagine, but whose relentless pursuit of greatness also brought suffering and instability.

Conclusion: The Eternal Conqueror

Alexander the Great was more than a king, more than a conqueror. He was a force of nature, a figure who reshaped the world through sheer will and vision. His life embodies the paradox of human ambition: the capacity to dream beyond limits, to build and to destroy, to seek immortality in deeds that outlast death.

Though his empire crumbled, his legacy endures—not only in history books but in the very fabric of global culture. He united East and West, spread ideas that continue to influence us, and carved a path that countless rulers have sought to follow.

In the end, Alexander reminds us that greatness is not measured only in territory or victories, but in the ability to inspire across time. He remains the eternal conqueror—not only of lands, but of imagination itself.