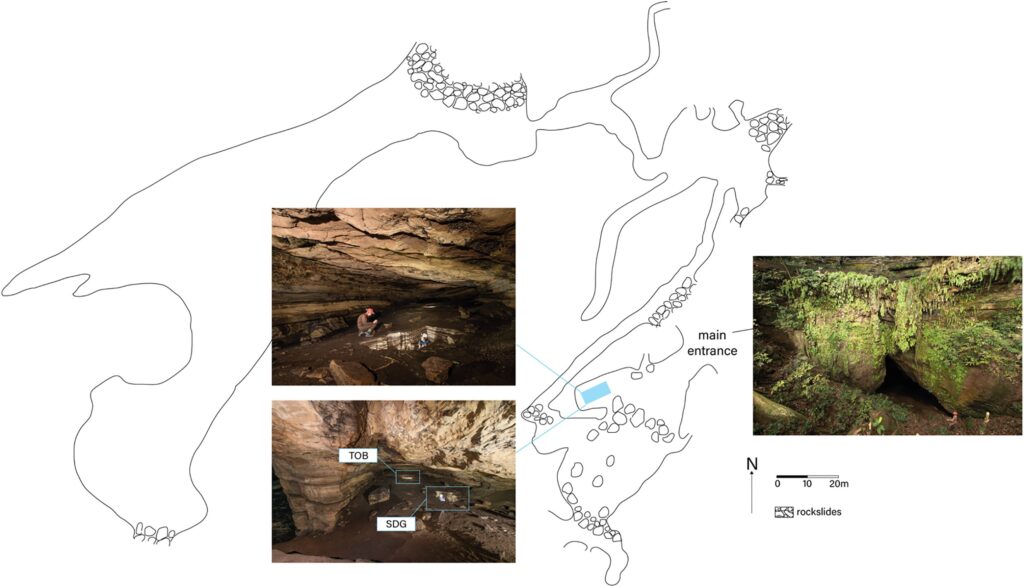

Deep in Gabon, tucked away from the harsh chemistry of the surrounding landscape, Pahon Cave has quietly held onto a story that much of central Africa has lost. Outside the cave, acidic soils relentlessly erase traces of the past. Inside, layers of guano-based sediment have acted like a natural archive, preserving thousands of years of human activity with rare clarity. For archaeologists, this makes Pahon Cave more than a shelter of stone. It is a place where time slowed down enough to be studied.

A new study published in the journal PLOS One takes readers into this cave, focusing on two test pits that together yielded a remarkable collection of evidence from the Late Stone Age. What emerged from those pits was not a tale of rapid technological change or dramatic cultural shifts, but something far more subtle and, in many ways, more intriguing. It was a story of continuity.

Five Thousand Years Beneath the Same Roof

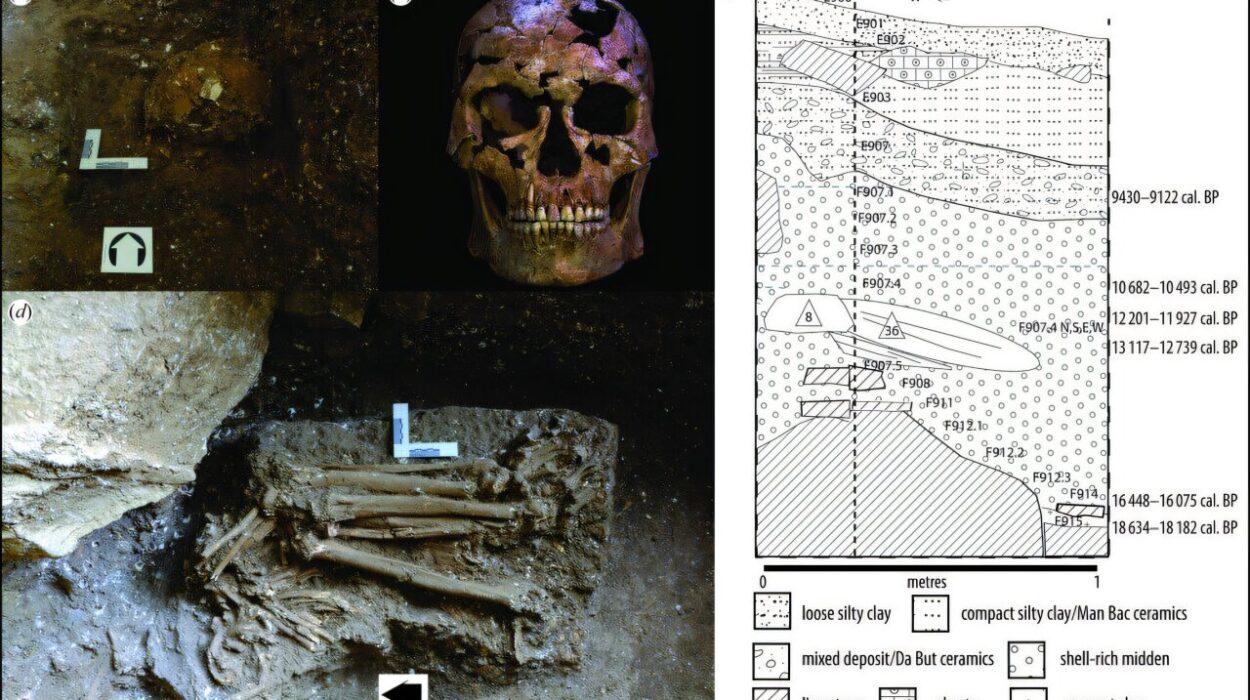

The cave’s interior is divided into five stratigraphic layers, each one a chapter in human history stretching from 7,427 years before present to 2,724 years before present. Within these layers, archaeologists recovered 1,131 stone artifacts. Of these, 985 were examined closely, revealing a pattern that challenged long-standing assumptions about how human technology evolves.

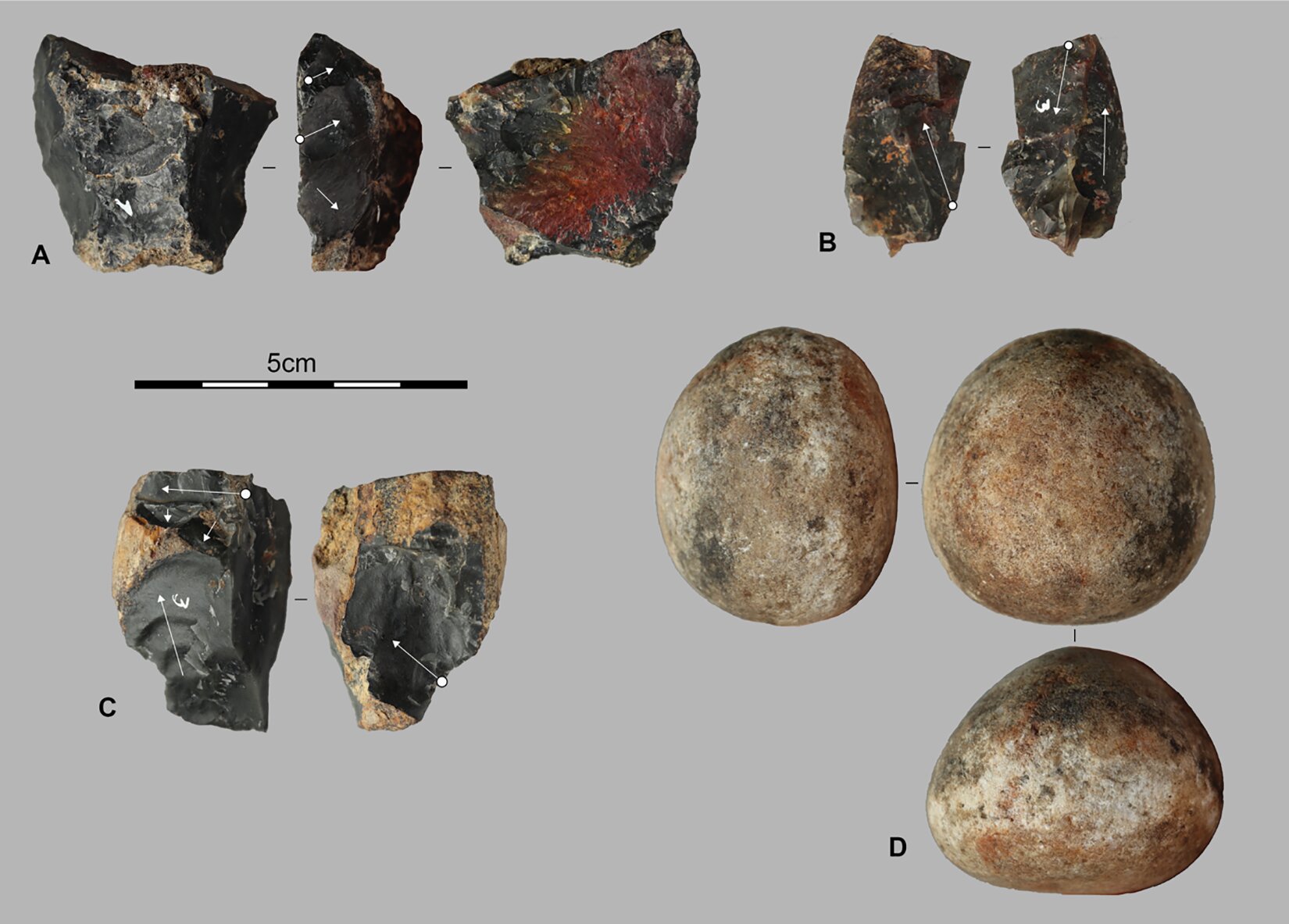

Most of these objects were not tools in the traditional sense. They were flakes. Chips and sharp fragments left behind during the making or maintenance of stone tools. An overwhelming 88 percent of the analyzed pieces fell into this category. Alongside them were a hammerstone and a fragment of a polished ax. That ax fragment stands out quietly but powerfully, offering evidence for an early date in the development of stone polishing in Atlantic Central Africa.

Yet the most striking finding was not a single artifact, but the long-term sameness of them all. Across more than 5,000 years, the stone tool technology at Pahon Cave remained stable, simple, and remarkably flexible. There was little sign of standardized or specialized tool types emerging over time. The flakes looked much the same from one layer to the next, as if generations of people had solved their daily problems using the same reliable approach.

When Simplicity Refuses to Disappear

To understand what these stone fragments meant, researchers categorized them by flake shape and examined signs of wear left behind by use. This careful work allowed them to reconstruct how tools were made and used, even when the tools themselves were never formally shaped or retouched.

What they found was consistency. The materials chosen, the way flakes were struck, and the way those flakes were used showed little variation across millennia. This was not technological stagnation born of limitation, but a system that worked well enough to endure.

The study authors describe it clearly in their own words. “Our study, based on a technological analysis, reveals a complete—though relatively simple—lithic operational sequence, characterized by unretouched, low-standardization stone flakes, often used as unmodified tools. This is a lithic industry that does not conform to the classical typology and instead reinforces the hypothesis of the diversity of Holocene lithic technical behaviors in Central Africa.”

This statement pushes back against a familiar narrative in archaeology. The Holocene is often associated with increasing complexity, standardized production, and specialized tools. But Pahon Cave tells a different story. According to the researchers, “Contrary to conventional views that associate the Holocene with complex and standardized production schemes, the industries from the Pahon Cave exhibit highly flexible technical systems, marked by variability and simplicity in both application and knapping know-how.”

Here, simplicity was not a failure to progress. It was a choice that endured.

The Echoes of Meals Long Finished

Stone tools tell one part of the story. Animal remains tell another. From the same layers that preserved flakes and fragments, archaeologists recovered 1,045 faunal remains. Many belonged to animals that had likely died naturally inside the cave, but others carried the unmistakable marks of human consumption.

The food waste left behind by people who used the cave as shelter paints a picture of daily life that feels surprisingly intimate. Giant snails appear frequently, alongside remains from small to medium-sized animals such as porcupines, bushpig, and antelope. These were not exotic feasts, but practical meals drawn from the surrounding environment.

The cave itself, however, was dominated by another presence entirely. Bats.

The Cave’s Original Residents

Bats were by far the most common animals found in Pahon Cave. Their bones filled the sediments in overwhelming numbers, reminding researchers that humans were not the cave’s primary occupants for much of its history.

As the study authors explain, “No less than 93% of all identified faunal remains are from large bats that typically inhabit caves. Fruit bats of the genus Rousettus are only found in trench SDG in which giant roundleaf bat (Macronycteris gigas) is also represented, albeit in smaller numbers.”

The distribution of bat species varied depending on where researchers dug. In trench TOB, which lay deeper within the cave, the picture was even simpler. “In trench TOB, somewhat deeper in the cave, the giant roundleaf bat is the sole bat species.”

While it is known that large bats can be captured for food, usually with nets, the researchers urge caution in interpretation. “Although it is known that large bats can be captured for food, usually with the aid of nets, we believe that the remains found in Pahon Cave represent mainly, if not exclusively, animals that died naturally.”

This distinction matters. It suggests that humans shared the cave intermittently with wildlife, rather than dominating it continuously. The cave was a shelter, not a permanent settlement.

A Quiet Mystery at the End of the Layers

Despite the wealth of material recovered, the story of Pahon Cave remains unfinished. The sample size, while impressive, is still limited. There are unanswered questions, especially about what eventually led to the decline of stone tool use in the region.

The artifacts show continuity, but continuity does not last forever. Somewhere beyond the final layer lies a transition that archaeologists have yet to fully understand. To reach it, the researchers point toward future work. More excavations, either deeper within the cave or in nearby sites, could expand the picture. Microscopic studies of wear on stone flakes could reveal more precise details about how they were used.

For now, the cave holds its secrets close.

Why This Story Matters

The discoveries at Pahon Cave matter because they challenge how we think about human history. They remind us that technological change is not always a straight line toward greater complexity. Sometimes, stability is the real innovation.

For more than 5,000 years, people returned to this cave and relied on simple stone flakes to meet their needs. They hunted, gathered, cooked, and sheltered themselves without dramatically altering their tools. Their choices were shaped by environment, tradition, and practicality rather than an abstract drive toward progress.

This research broadens our understanding of the Holocene in Central Africa, reinforcing the idea that human behavior during this period was diverse and adaptable. By preserving such a long and continuous record, Pahon Cave allows archaeologists to see that diversity clearly.

In a world that often equates advancement with constant change, this cave offers a quieter lesson. Sometimes, what works is worth keeping.

More information: Marie-Josée Angue Zogo et al, Pahon Cave, Gabon: New insights into the Later Stone Age in the African rainforest, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0336405