In the fading years of the Late Bronze Age, when mighty empires stretched across the eastern Mediterranean and kings claimed dominion from Anatolia to the banks of the Nile, a shadow began to stir on the seas. They came in ships, fierce and sudden, raiding coasts, toppling cities, and leaving behind a wake of destruction so profound that ancient scribes remembered them as a force of chaos—the Sea Peoples.

The name itself is enigmatic. The “Sea Peoples” was not what they called themselves but rather the label given to them in Egyptian records, where Pharaohs recorded desperate battles against these marauders from beyond the horizon. They appeared suddenly around the 13th century BCE, sweeping across the Mediterranean world, and their impact was so great that many historians link them to the collapse of Bronze Age civilizations around 1200 BCE. Yet who they were, where they came from, and what drove their sudden movement remain questions that continue to stir debate and fascination today.

The origin of the Sea Peoples is a riddle woven from fragments of inscriptions, archaeology, and myth. To explore their beginnings is to venture into the turbulent crossroads of history, where climate, migration, and war collided to reshape the world.

The Bronze Age World Before the Storm

Before the Sea Peoples emerged, the eastern Mediterranean was a glittering web of civilizations. Egypt flourished along the Nile under the New Kingdom. The Hittite Empire dominated Anatolia, projecting power as far as northern Syria. The Mycenaeans ruled the Aegean, their palaces filled with warriors and scribes. The Canaanite city-states dotted the Levant, trading luxury goods and raw materials between empires.

This interconnected world depended on fragile networks of trade and diplomacy. Ships carried copper from Cyprus, tin from as far as Afghanistan, grain from Egypt, and timber from Lebanon. Kings wrote letters to one another on clay tablets, addressing each other as “brothers” in the language of alliance.

Yet beneath this glittering surface lay vulnerabilities. The system was highly interdependent, and any disruption—famine, rebellion, or invasion—could send ripples across the entire region. The Sea Peoples arrived at precisely the moment when these vulnerabilities were exposed, and their sudden appearance accelerated a crisis that would change the course of history.

The First Whispers of the Invaders

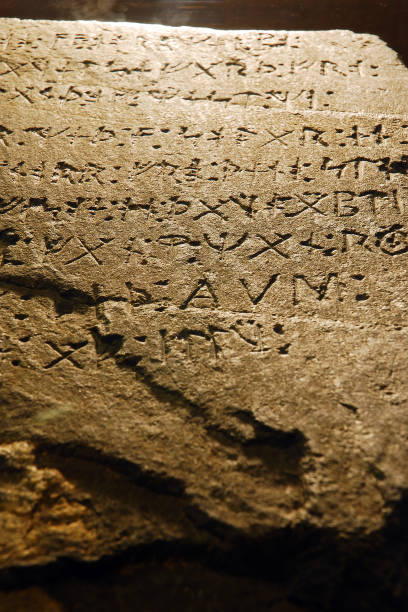

Our earliest glimpses of the Sea Peoples come not from archaeology but from words carved in stone. Egyptian inscriptions, particularly those from the reigns of Pharaohs Merneptah (c. 1213–1203 BCE) and Ramesses III (c. 1186–1155 BCE), describe battles with invaders who came “from the midst of the sea.”

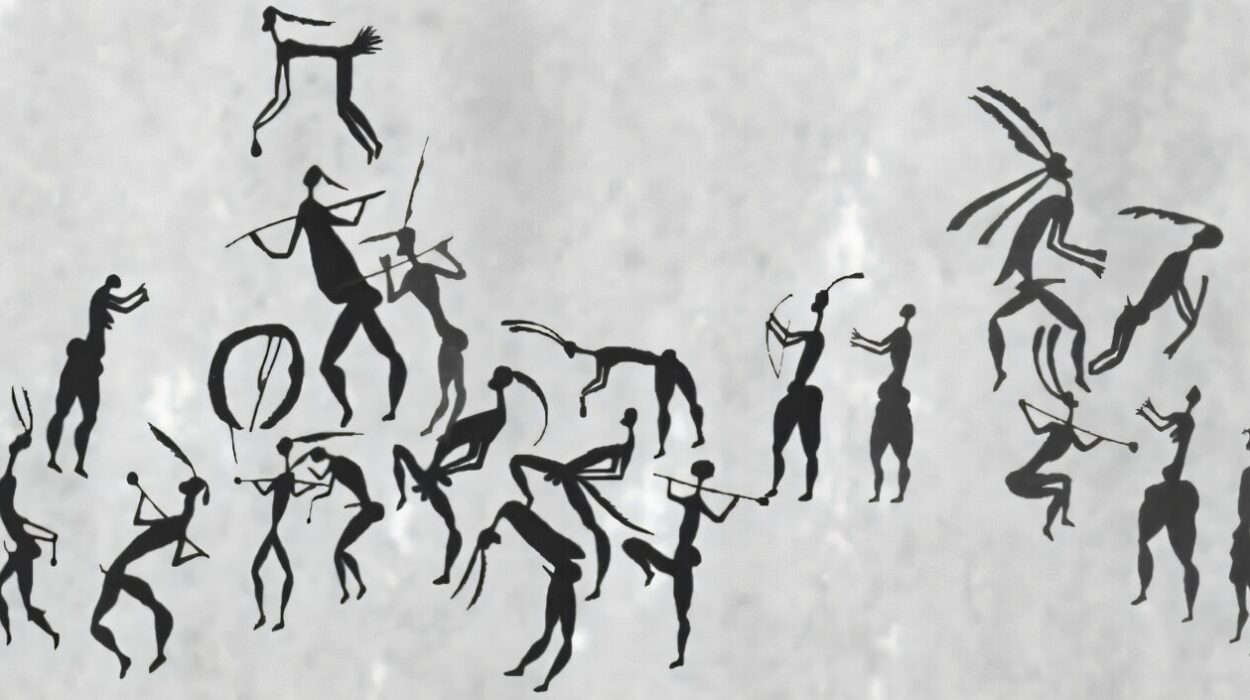

On the walls of the mortuary temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu, a vivid relief depicts ships locked in combat, their sails billowing as warriors hurl spears and fire arrows. The Egyptians described their foes as a coalition of peoples with names such as the Peleset, Tjeker, Sherden, Shekelesh, and Denyen. To the Egyptians, they were not a single people but a confederation, united by the sea and by war.

But the Egyptians tell only one side of the story. For the Sea Peoples themselves, we have no written accounts. Their voices are lost, leaving us with the challenge of piecing together their origins from the shadows of archaeology and the echoes of other civilizations.

A Patchwork of Peoples

The term “Sea Peoples” is a modern scholarly invention, grouping together different tribes and groups that Egyptian texts listed separately. This confederation seems to have included several distinct cultures, each with its own homeland, traditions, and reasons for moving across the seas.

The Sherden are among the most frequently mentioned. They appear in Egyptian records even before the great invasions, sometimes as mercenaries serving in Pharaoh’s armies, sometimes as enemies. Their helmets with horn-like projections, depicted in Egyptian art, have led some scholars to suggest they may have originated from Sardinia or elsewhere in the western Mediterranean.

The Peleset are often associated with the Philistines of the Hebrew Bible, who settled along the southern coast of Canaan after the great upheavals. Archaeological evidence from Philistine sites shows a blend of local Canaanite traditions with Aegean influences in pottery and architecture, suggesting that the Peleset may have come from the Aegean world, perhaps from Crete or other islands.

The Denyen may have connections to the later Greek Danaans of Homeric epic, though the link remains speculative. The Shekelesh have been associated with Sicily, while the Tjeker may have originated in Anatolia.

Taken together, these groups paint a picture not of a single nation but of a migratory wave involving multiple peoples, perhaps displaced by crises in their homelands and united by the shared necessity of survival.

Theories of Origin

The question of where the Sea Peoples came from has intrigued historians for centuries. Several main theories have emerged, each drawing on different strands of evidence.

One possibility is that they came from the Aegean region, particularly from Mycenaean Greece and Crete. Around 1200 BCE, the Mycenaean palace system collapsed, leaving cities abandoned and trade routes disrupted. Earthquakes, internal strife, and foreign invasions may have forced people to seek new lands across the sea. The Aegean-style pottery found in Philistine settlements lends weight to this idea.

Another theory places their origins in Anatolia. The fall of the Hittite Empire around 1200 BCE created waves of refugees and mercenaries. Groups from western Anatolia may have turned to the sea in search of new homes, raiding and migrating southward toward the Levant and Egypt.

Some suggest connections with the central and western Mediterranean. The similarities between the names of the Sherden and Sardinia, or the Shekelesh and Sicily, hint at origins further west. If so, the Sea Peoples may represent a vast movement of peoples from multiple directions converging on the eastern Mediterranean.

It is also possible that climate played a role. Studies of pollen and sediments suggest a period of prolonged drought and famine around 1200 BCE. Such environmental stress could have destabilized societies, forcing migrations and sparking conflict. The Sea Peoples, then, may have been both migrants fleeing hardship and opportunists exploiting the weakness of collapsing empires.

The Great Collisions

The arrival of the Sea Peoples was not a single event but a series of waves. They attacked cities along the Levantine coast, struck Cyprus, and pressed into Anatolia. The Hittite Empire, already weakened by internal struggles and external threats, collapsed under the strain, leaving behind little more than scattered city-states.

In Egypt, Pharaoh Merneptah faced an invasion of Libyans allied with groups identified as Sea Peoples around 1208 BCE. He claimed victory, but the threat was not extinguished. A few decades later, during the reign of Ramesses III, the Sea Peoples launched a massive assault by land and sea.

The battle is immortalized at Medinet Habu, where Ramesses boasts of defeating the invaders. He describes them as coming with their families, their possessions, their oxen, seeking to settle in Egypt rather than simply raid. Ramesses claimed to have crushed them, but many scholars believe that while Egypt repelled them, some groups simply moved on and settled in Canaan and elsewhere.

Settlement and Legacy

Though they failed to conquer Egypt, the Sea Peoples did not vanish. Instead, they left enduring marks across the eastern Mediterranean.

The Peleset became the Philistines, remembered in the Bible as rivals of the Israelites. Archaeological excavations at sites such as Ashkelon, Ekron, and Gath reveal a distinct Philistine culture that blended Aegean styles with Canaanite traditions, showing how migrants adapted and merged with local populations.

The Sherden, once feared as raiders, became valued mercenaries in Egyptian service, a testament to how enemies could be absorbed into the empire’s structure. Other groups may have integrated into local societies along the Levantine coast, losing their distinct identities but leaving traces in names and material culture.

In this way, the Sea Peoples were not only destroyers but also builders, contributing to the cultural mosaic of the Iron Age Levant.

The Collapse of the Bronze Age

The story of the Sea Peoples cannot be separated from the wider crisis of the Late Bronze Age. Between 1200 and 1150 BCE, nearly every major power of the eastern Mediterranean fell into ruin. The Hittites disappeared. The Mycenaean palaces burned. Many Canaanite cities were abandoned. Even Egypt, though it survived, entered a period of decline.

Were the Sea Peoples the cause of this collapse, or merely a symptom? The answer may lie somewhere in between. The collapse was likely the result of a “perfect storm” of factors: climate change, famine, earthquakes, rebellions, breakdown of trade, and invasions. The Sea Peoples were both products of this instability and agents who intensified it. They were the human face of a broader wave of chaos that swept away the old order and ushered in a new era.

The Emotional Pull of Mystery

Part of the fascination with the Sea Peoples lies in their mystery. They appear suddenly in the records, wreak havoc, and then disappear into the fabric of new societies. We do not know what they called themselves, what languages they spoke, or what songs they sang on their voyages. We glimpse them only through the eyes of their enemies, who saw them as terrifying outsiders from beyond the sea.

And yet, perhaps it is this very mystery that makes them compelling. They embody the drama of migration, the struggle for survival, the clash of cultures at turning points in history. They remind us that civilizations are not eternal, that human societies are vulnerable to forces both natural and human. They also remind us of the resilience of life, for out of collapse came renewal, out of destruction came new beginnings.

Conclusion: Children of the Sea and of History

The origin of the Sea Peoples remains one of history’s great puzzles. Were they Aegean refugees, Anatolian warriors, or western migrants? The evidence suggests that they were many things at once—a coalition of displaced peoples, drawn together by necessity, who struck at the heart of the Bronze Age world.

Their story is not just about warfare and collapse. It is about movement, adaptation, and transformation. It is about how humans respond to crisis, sometimes with violence, sometimes with resilience. The Sea Peoples were not merely destroyers of civilizations but also participants in the birth of a new world—the Iron Age, with its kingdoms, its new trade networks, and its cultural fusions.

To study the Sea Peoples is to look into a mirror of humanity itself: restless, resilient, and forever shaped by the tides of history. They came from the sea, and in a sense, they remain there still, drifting in the imagination, their origins obscured, their legacy enduring.