The Bronze Age was a defining period in human history, bridging the gap between the stone tools of prehistory and the complex civilizations of antiquity. One of the most fascinating chapters of this era is the transition from the Middle to the Late Bronze Age in Central Europe. Recent bioarchaeological research into the cemetery at Tiszafüred-Majoroshalom, a key Bronze Age site in Hungary, has shed new light on this transformative time, revealing how profound changes in diet, social structure, and mobility redefined life for people around 1500 BC. The findings have challenged long-held assumptions about the people of the Tumulus culture, showing that their society was far more complex than previously thought.

This multidisciplinary research, led by Tamás Hajdu from Eötvös Loránd University and Claudio Cavazzuti from the University of Bologna, has provided a unique glimpse into how shifts in lifestyle, dietary habits, and social dynamics can mark a turning point in history. The study was recently published in Scientific Reports and has already sparked intense discussion within the archaeological community.

A Glimpse into the Past: Tiszafüred-Majoroshalom Cemetery

The Tiszafüred-Majoroshalom cemetery is situated in the Great Hungarian Plain, an area rich in archaeological heritage. The site was used for burial practices during two important cultural phases: the Middle Bronze Age, associated with the Füzesabony culture, and the Late Bronze Age, linked to the Tumulus culture. The cemetery thus provides a rare opportunity to study a population across a period of significant transition, roughly from 1600 to 1300 BC.

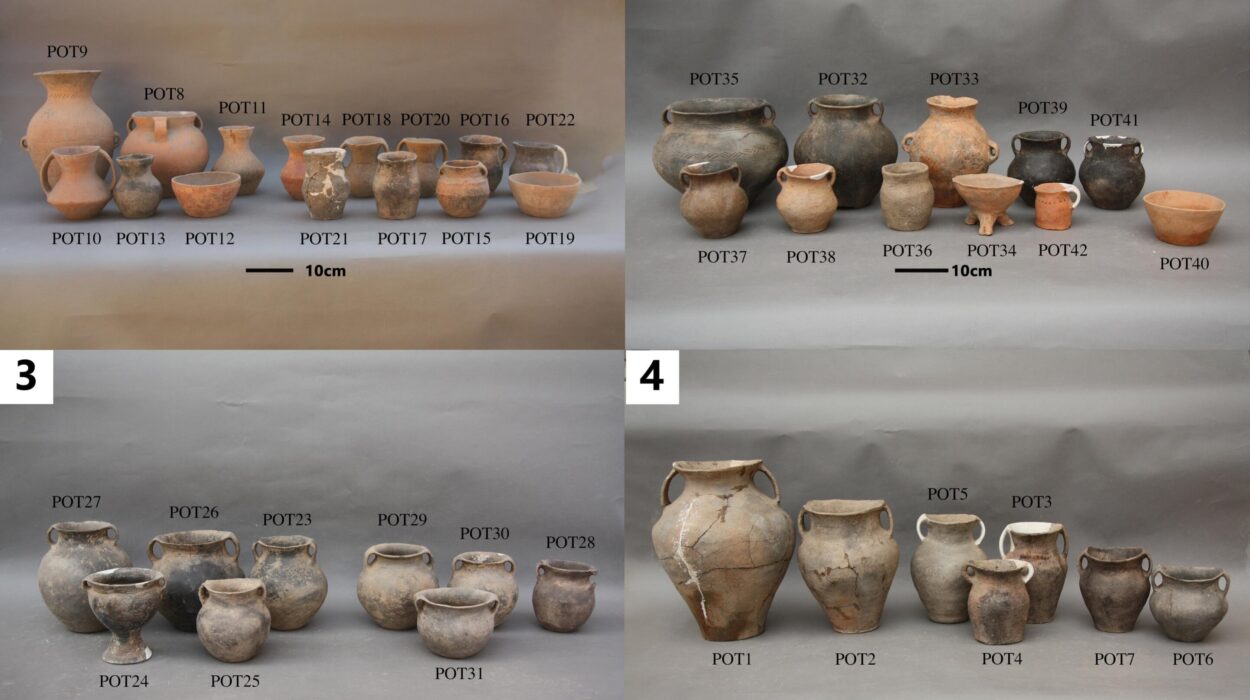

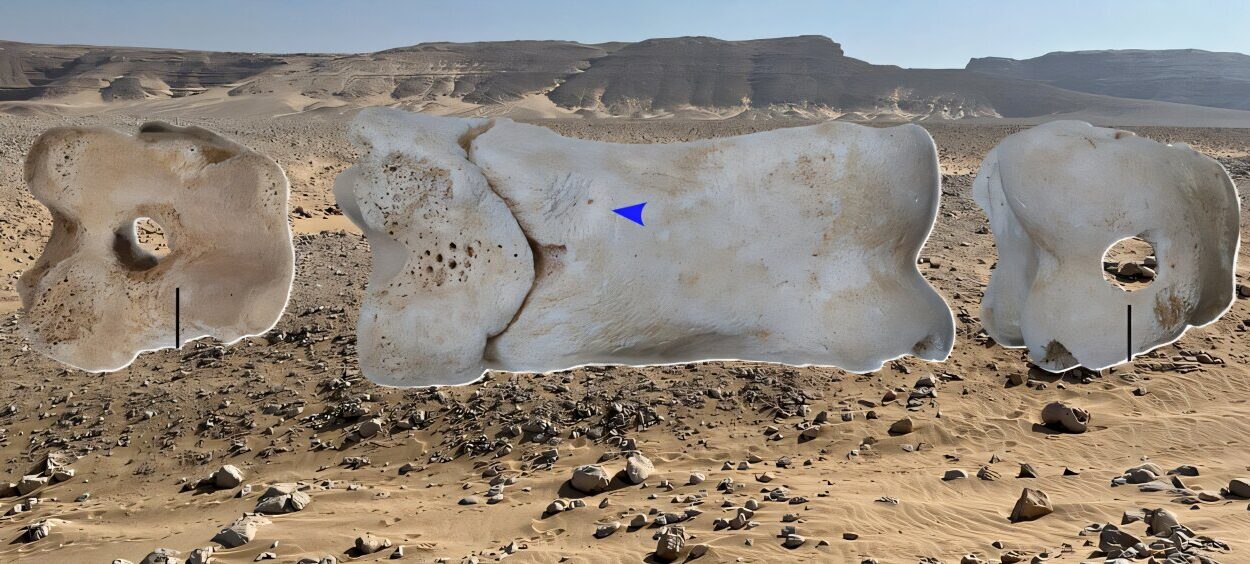

The graves found at Tiszafüred-Majoroshalom contain a wealth of material culture, including pottery, weapons, and ornaments. These artifacts, combined with bioarchaeological evidence from human remains, offer a detailed picture of the lives of people who lived over three millennia ago. The research team utilized cutting-edge techniques to analyze isotopic data from bones and teeth, shedding light on ancient diets, mobility, and social structures. By examining the remains of both the Füzesabony and Tumulus populations, the researchers were able to compare the ways in which people’s lives had changed over time, offering a clearer understanding of the broader transformations occurring across Central Europe.

Diet and Subsistence: A Shift from Diversity to Uniformity

One of the most striking findings from the bioarchaeological investigation is the shift in diet between the Middle and Late Bronze Ages. Nitrogen stable isotope analysis revealed that, during the Middle Bronze Age, people had a more diverse diet that included a significant amount of animal proteins. There were noticeable differences in dietary access across the society, with some individuals consuming more meat than others. This variation likely reflects social stratification, where higher-status individuals had better access to premium food sources.

However, by the Late Bronze Age, the diversity in diet had greatly decreased. People began to consume more plant-based foods, and their overall diet became much poorer in terms of animal protein. This change may have been influenced by broader shifts in the social structure and subsistence strategies. The Late Bronze Age saw the introduction of broomcorn millet into the diet—a fast-growing crop that was highly energy-dense and suited to the local climate. Carbon isotope analysis confirmed that millet was first consumed in the region around this time, making it the earliest known instance of millet consumption in Europe.

The introduction of millet is particularly significant because it suggests that the people of the Tumulus culture were beginning to adapt to changing environmental conditions, possibly due to climatic fluctuations or shifts in agricultural practices. Millet could be grown in areas that were less suitable for traditional cereals like wheat or barley, offering a new source of food for communities experiencing pressure on their agricultural systems.

Mobility Patterns: A Decrease in Immigration

Another key aspect of the research was the investigation into mobility patterns. Strontium isotope analysis of human remains indicated that there were significant differences in the origins of the populations buried at Tiszafüred-Majoroshalom. During the Middle Bronze Age, there was a noticeable presence of immigrants—people who had likely moved from surrounding regions, including the Upper Tisza and the northern Carpathians. This suggests that the Middle Bronze Age communities were part of a broader network of exchange and migration across Central Europe.

However, by the Late Bronze Age, the situation changed. Fewer immigrants were identified, and those who did arrive came from more distant regions, such as Transdanubia and the Southern Carpathians. The decline in immigration suggests that the mobility of people may have decreased during this period, perhaps due to changes in social organization or a shift toward more localized settlement patterns.

Radiocarbon dating supports the idea of increased mobility and migration beginning around 1500 BC, which coincides with the arrival of the Tumulus culture in the Great Hungarian Plain. This migration likely brought new people into the region, but it also marks the beginning of a reorganization of social and economic structures. The change in migration patterns may reflect broader shifts in the political and economic landscape of Central Europe at the time.

Social Structure: From Centralized to Decentralized

One of the most profound changes observed in the Tiszafüred-Majoroshalom site was the shift from a more centralized to a more decentralized social structure. The Middle Bronze Age was characterized by large, fortified settlements, often referred to as tell settlements, where people lived in close-knit communities. These settlements were often surrounded by defensive walls, indicating a need for protection and a more hierarchical organization.

In contrast, by the Late Bronze Age, many of these tell settlements were abandoned, and the population dispersed into smaller, less centralized settlements. This shift in settlement patterns reflects a transformation in social organization. The once tightly-knit communities of the Middle Bronze Age gave way to a more fragmented social system, where power and influence were likely distributed more evenly among different groups.

This decentralization may also explain the changes in diet observed during this period. Without the centralized structures of the earlier phase, access to resources may have become more egalitarian, resulting in a more uniform, though poorer, diet for the majority of the population. The loss of social stratification in the Late Bronze Age may also explain why the differences in animal protein consumption were less pronounced in this period.

Rethinking the Tumulus Culture: A Challenge to Prevailing Theories

The research conducted at Tiszafüred-Majoroshalom challenges several long-held assumptions about the Tumulus culture. For decades, archaeologists have believed that the people of the Tumulus culture were primarily pastoralists, engaged in large-scale animal husbandry and frequent migration. This view was based on the assumption that the presence of tumulus (burial mounds) and the lack of large-scale settlements indicated a mobile, herding-based society.

However, the evidence from Tiszafüred-Majoroshalom suggests a different story. While it is true that the Tumulus culture was associated with burial mounds, the lifestyle of its people appears to have been more complex than simple pastoralism. The bioarchaeological data reveals a more varied diet, a decrease in mobility, and a shift in social organization—indicating that the people of the Late Bronze Age may have been transitioning to a more settled, agricultural lifestyle, despite the prevailing assumption of pastoralism.

The study also emphasizes the importance of integrating traditional archaeological methods with modern bioarchaeological techniques to gain a fuller understanding of ancient societies. By combining material culture, isotopic analyses, and radiocarbon dating, researchers are able to reconstruct a more nuanced picture of how societies evolved during this pivotal period in history.

Conclusion: A New Understanding of the Bronze Age Transition

The bioarchaeological research at Tiszafüred-Majoroshalom has provided invaluable insights into the lives of people living around 1500 BC. The findings reveal a society undergoing profound changes in diet, social organization, and mobility. The shift from a more diverse and stratified diet to a more uniform and plant-based one, the decrease in mobility, and the abandonment of centralized settlements all point to a period of significant transformation in Central Europe.

These results challenge our understanding of the Tumulus culture and force us to reconsider the role of pastoralism in the Late Bronze Age. The people of this period were not simply nomadic herders; they were adapting to new circumstances, incorporating new crops into their diets, and reorganizing their social structures in response to changing environmental and political conditions.

Ultimately, the Tiszafüred-Majoroshalom cemetery stands as a testament to the complexity of human societies during the Bronze Age. By integrating bioarchaeology with traditional archaeology, researchers are able to uncover the subtle yet significant changes that marked this critical period in history—changes that continue to shape our understanding of the ancient world today.

Reference: Claudio Cavazzuti et al, Isotope and archaeobotanical analysis reveal radical changes in mobility, diet and inequalities around 1500 BCE at the core of Europe, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-01113-z