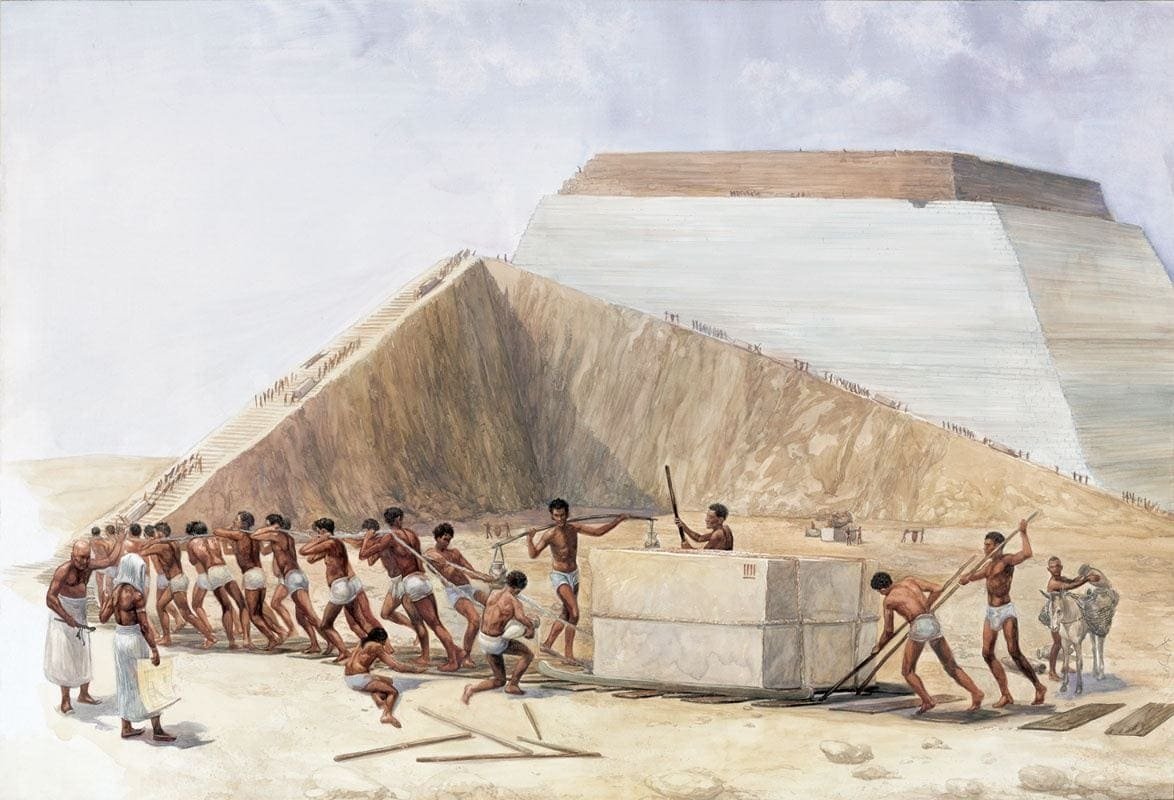

When people think of the Great Pyramids of Giza, images of towering stone structures silhouetted against the desert sun come to mind. The pyramids are among the most iconic monuments of human civilization, standing as enduring symbols of ancient Egypt’s power, ambition, and ingenuity. For centuries, they have stirred both awe and mystery: How were these colossal structures built? Who moved the millions of limestone blocks? What kind of lives did the builders live?

For much of history, the narrative was dominated by myths. Ancient Greek writers like Herodotus described armies of slaves laboring under the whips of cruel overseers. Hollywood films reinforced this image, showing endless chains of suffering captives dragging stones beneath the desert sun. But modern archaeology has shattered this myth, revealing a very different story—one not of slaves but of skilled workers, organized communities, and a “lost city” that supported the immense effort of pyramid construction.

This lost city, discovered near the Giza plateau, has unveiled the human side of one of the world’s greatest architectural achievements. It is a story not only of monumental stones but of bread, beer, cattle, family life, and a workforce that left behind their own legacy—one etched in broken pottery, carefully laid out streets, and skeletal remains that whisper of hard labor and human resilience.

The Myth of the Slave Builders

For centuries, the popular imagination was haunted by the belief that slaves, possibly Hebrew captives, were forced to build the pyramids. This interpretation persisted for cultural and religious reasons, reinforced by biblical narratives of slavery in Egypt. Yet archaeological evidence contradicts this entirely.

The pyramids were built not by chained laborers but by free citizens of Egypt—well-fed, well-housed, and highly skilled workers who took pride in their contribution to monuments that were as much religious as political. The pyramids were not mere tombs but gateways to eternity for the pharaohs, and building them was an act of devotion as well as civic duty.

The lost city of the pyramid workers provides undeniable proof of this reality. Here, archaeologists found not prison barracks but organized housing complexes. They uncovered not whips but bread molds, fish bones, and cattle remains—evidence of a diet richer than that of many Egyptian peasants. The workers were laborers, yes, but they were also artisans, masons, engineers, bakers, brewers, and administrators.

The Discovery of the Workers’ City

The modern story of the workers’ city begins in the late 20th century. Archaeologists, led by Mark Lehner and his team from the Giza Plateau Mapping Project, began investigating areas south of the Great Sphinx. What they found changed the world’s understanding of pyramid building forever.

Excavations revealed a sprawling settlement dating to the Fourth Dynasty (c. 2575–2465 BCE), the era of Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure—the pharaohs who constructed the great pyramids of Giza. The site included barracks-like galleries, bakeries, breweries, storage facilities, and even evidence of centralized administration.

The city was not permanent but seasonal, designed to house rotating crews of workers who labored on the pyramids. Estimates suggest that as many as 20,000 to 30,000 workers lived and worked in and around this city at the height of construction. It was a logistical masterpiece, as impressive in its own way as the pyramids themselves.

Life in the Lost City

Walking through the remains of the workers’ city today, one can almost imagine the rhythms of daily life. Archaeologists uncovered long galleries, each capable of housing about 40 workers. These were not luxurious accommodations, but they provided shelter, order, and community.

The workers’ diet was surprisingly rich. Excavations revealed vast quantities of cattle bones, suggesting that beef was a regular staple—remarkable, since meat was a luxury for most Egyptians. Alongside beef were sheep, goats, fish, bread, and beer. The presence of thousands of bread molds and brewing vats suggests that food production was industrial in scale, designed to keep the workforce strong and productive.

Evidence of healthcare was also found. Skeletal remains showed that workers who suffered broken bones received treatment, sometimes healing well enough to allow them to return to work. This level of care suggests that workers were valued members of society, not expendable slaves.

There were also traces of leisure and spiritual life. Small artifacts, amulets, and graffiti hint at the personal beliefs and daily moments of the workers—reminders that they were not faceless laborers but individuals with hopes, fears, and identities.

The Organization of the Workforce

Building a pyramid was not simply a matter of brute force. It required careful organization, logistics, and administration. The workers’ city was the nerve center of this system.

Crews were divided into teams, often named after royal or divine symbols. Graffiti discovered on stone blocks reveal names like “The Friends of Khufu” or “The Drunkards of Menkaure.” These names carried pride and identity, transforming groups of workers into cohesive units with a sense of belonging.

Each team had specific tasks: quarrying limestone, transporting blocks, constructing ramps, or finishing the surfaces of the pyramid. Others were responsible for producing food, maintaining tools, or managing supplies. The pyramid site was a living machine, powered by human coordination on a scale rarely seen in history.

The city itself was laid out with precision. Streets separated functional areas, while large administrative buildings suggest the presence of overseers and scribes who recorded deliveries of food and supplies. This bureaucracy ensured that tens of thousands of people could be housed, fed, and managed efficiently—a feat as impressive as lifting the pyramid stones themselves.

The Human Cost of Monumental Ambition

While the workers were not slaves, their lives were far from easy. Skeletal remains tell the story of bodies worn down by backbreaking labor. Signs of arthritis, spinal injuries, and fractured bones were common. The men and women who built the pyramids carried burdens heavier than most of us can imagine, day after day, year after year.

Yet these remains also tell of resilience and determination. Many injuries showed signs of healing, suggesting medical care and community support. These people were not abandoned to their fate but cared for by others—a testament to the social bonds within the city.

The pyramids themselves stand as silent witnesses to the sacrifices of these workers. Each stone block, carefully positioned, is not only a monument to a pharaoh’s ambition but also a testament to the sweat, skill, and humanity of the laborers who made it possible.

Bread, Beer, and Cattle: The Fuel of Pyramid Building

One of the most fascinating discoveries in the workers’ city was the sheer scale of food production. Archaeologists uncovered bakeries with rows of conical bread molds, breweries with massive vats, and storage areas filled with animal bones.

Bread and beer were the staples of the Egyptian diet, providing both energy and hydration. The beer was not like the modern beverage but a thick, nutritious brew consumed daily. Cattle were slaughtered regularly, a sign that workers were well-fed. This level of diet indicates that pyramid construction was a national project supported by the state, not a burden pushed onto marginalized groups.

Food was not just sustenance—it was morale. Feeding workers generously was both practical and symbolic, reinforcing their importance and their role in building monuments for eternity.

Women and Families in the Workers’ City

Though the workforce was predominantly male, evidence suggests that women and children were also part of the community. Some were likely involved in food production, weaving, or maintaining daily life in the city. Burial remains included women and infants, suggesting that families may have lived alongside workers, at least for part of the construction period.

This human dimension transforms our understanding of the pyramids. They were not built in isolation by anonymous laborers but by living communities—families who laughed, prayed, worked, and grieved together on the edge of the desert.

A Civilization in Action

The lost city of the pyramid workers is more than an archaeological site; it is a snapshot of ancient Egyptian civilization in motion. It shows the integration of religion, politics, economy, and labor into a single enterprise.

For the pharaohs, pyramids were eternal symbols of divine kingship. For the workers, they were projects that bound them to the state, to their communities, and to the gods. The act of building pyramids was itself a ritual, a way of ensuring the order of the cosmos, known as ma’at.

The workers’ city reveals that pyramid building was not simply about stone and labor—it was about unity, identity, and the shared belief in something greater than individual lives.

Rediscovering the Humanity Behind the Monuments

For centuries, the pyramids were seen only as monuments to kings. Today, thanks to the discovery of the workers’ city, we can see them also as monuments to people—the thousands of ordinary Egyptians whose names are lost but whose efforts endure.

Every broken bread mold, every cattle bone, every healed fracture tells us that the pyramids were built not just by rulers but by communities. They remind us that behind every great monument in history lies the labor, resilience, and humanity of countless individuals.

The Legacy of the Lost City

The discovery of the workers’ city has forever changed how we view the pyramids. No longer can they be seen solely as the symbols of royal power—they are also symbols of collective human effort.

The city tells us that ancient Egyptians were not only brilliant architects but also skilled organizers, capable of mobilizing resources, feeding thousands, and sustaining communities over decades. It tells us that the pyramids were national projects that united people in a shared vision of eternity.

Most of all, it tells us that the workers were not slaves but citizens who lived, labored, and left behind a hidden chapter of history—one that was nearly lost but is now being rediscovered piece by piece.

Conclusion: Remembering the Builders

The Great Pyramids of Giza will always inspire awe. They are colossal, mysterious, and enduring. But perhaps their greatest significance lies not just in their size but in the story of the people who built them.

The lost city of the pyramid workers reminds us that history is not only about kings and monuments—it is about the ordinary people whose hands shaped the stones, whose backs carried the weight, and whose lives filled the desert with laughter, sweat, and song.

In rediscovering this city, we rediscover the humanity of the ancient world. We see the pyramids not only as tombs of pharaohs but as monuments to the resilience, ingenuity, and spirit of the people of Egypt.

The pyramids stand as eternal symbols of human ambition, but the workers’ city ensures that they also stand as eternal symbols of human community.