In the arid, sun-drenched soils of southwest Spain, just outside the modern town of Valencina de la Concepción, archaeologists have uncovered a mystery that transcends time and tide. Hidden beneath the surface of a once-bustling Copper Age mega-village, a massive tooth—an ancient relic from a sperm whale—lay waiting to tell a story 5,000 years in the making.

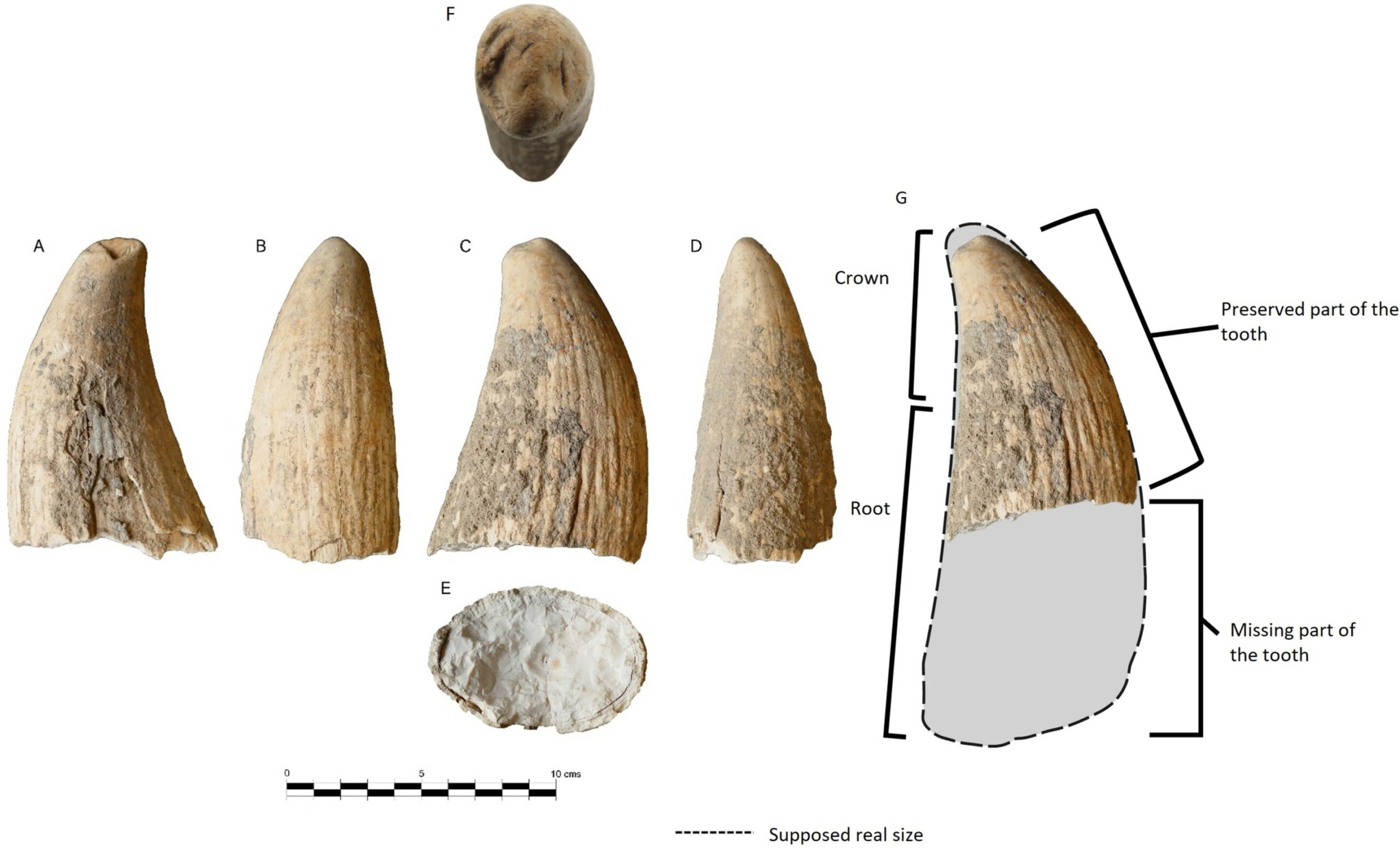

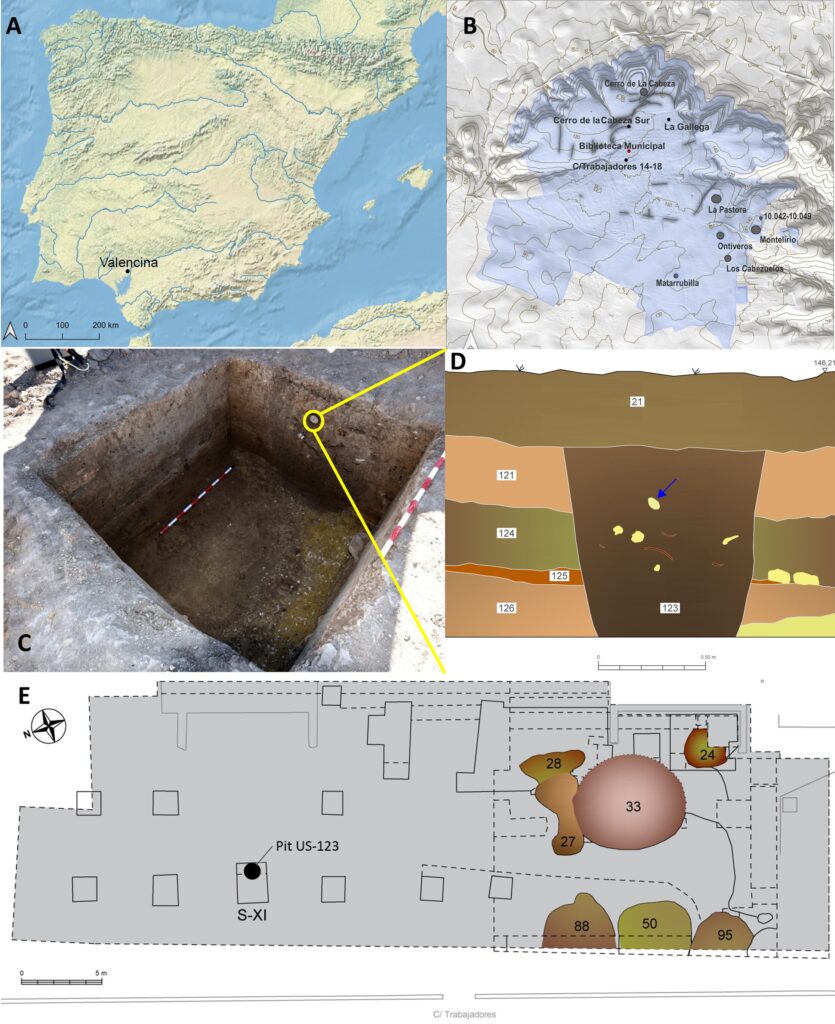

Discovered in 2018 during excavations at the Nueva Biblioteca sector of the Valencina site, the tooth stood out immediately. Measuring 17 centimeters in height, 7 centimeters wide, and weighing more than half a kilogram, this ocean-born artifact was entirely out of place among the inland settlement’s clay pots, stone tools, and burial pits.

Now, as detailed in a new study published in PLOS One, researchers believe this single marine tooth may shift our understanding of prehistoric life, shedding rare light on the connections between early Iberian communities and the distant, unseen forces of the sea.

From the Deep to the Dust: A Tooth’s Unlikely Journey

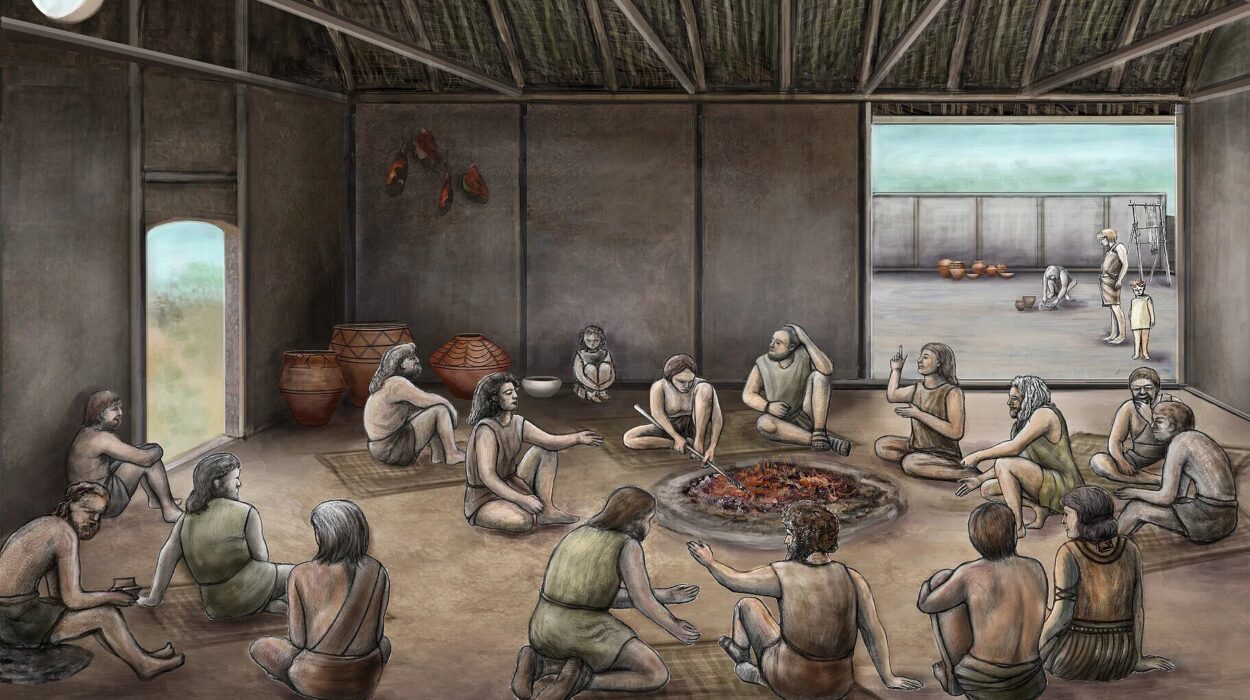

Roughly between 5,300 and 4,150 years ago, during the height of the Copper Age, Valencina thrived as one of Europe’s largest and most sophisticated settlements. With thousands of inhabitants, advanced architecture, and rich burial traditions, it was a hub of culture, trade, and ritual. But even within such a dynamic context, the sperm whale tooth stood out as wholly unique.

This was not just any artifact—it was the first of its kind ever recorded in Late Prehistoric Iberia.

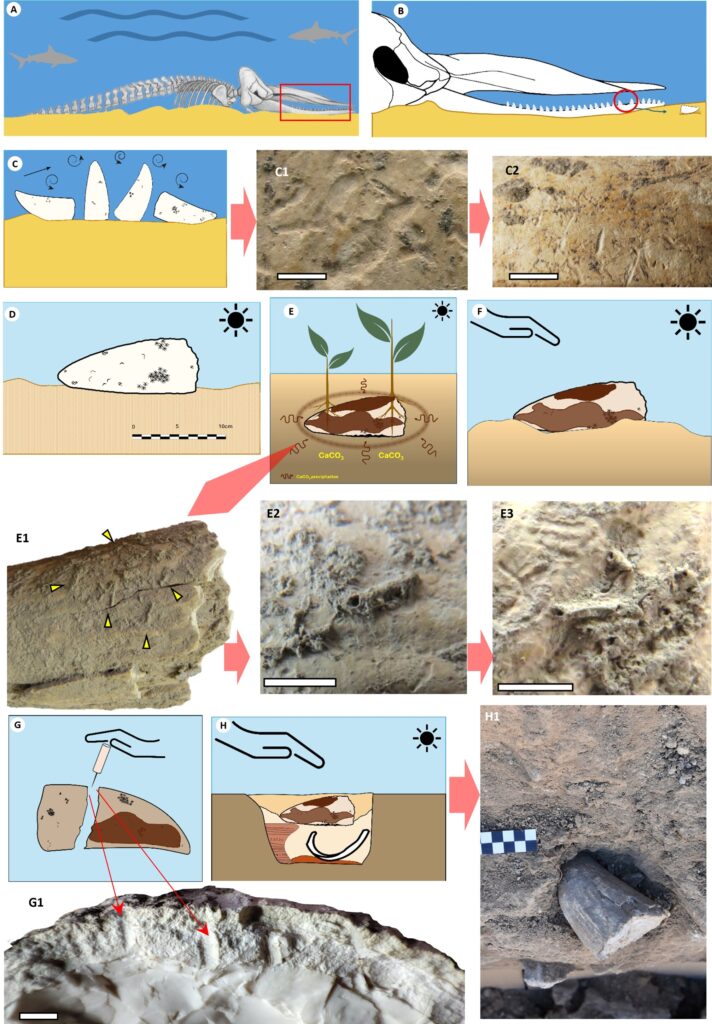

The tooth bore the fingerprints of a long aquatic voyage. Tiny tunnels etched by marine worms and encrustations left by barnacles revealed that it had spent time on the ocean floor. Shark bite marks on its surface painted a vivid, if grim, scene: the whale had likely died naturally, sunk to the depths, and become part of the marine food chain before parts of its body washed ashore.

There, perhaps lying half-buried in wet sand, it was discovered by ancient humans. Carried inland, it was no longer just flotsam from a carcass—it became something meaningful.

Ancient Hands, Sacred Intent

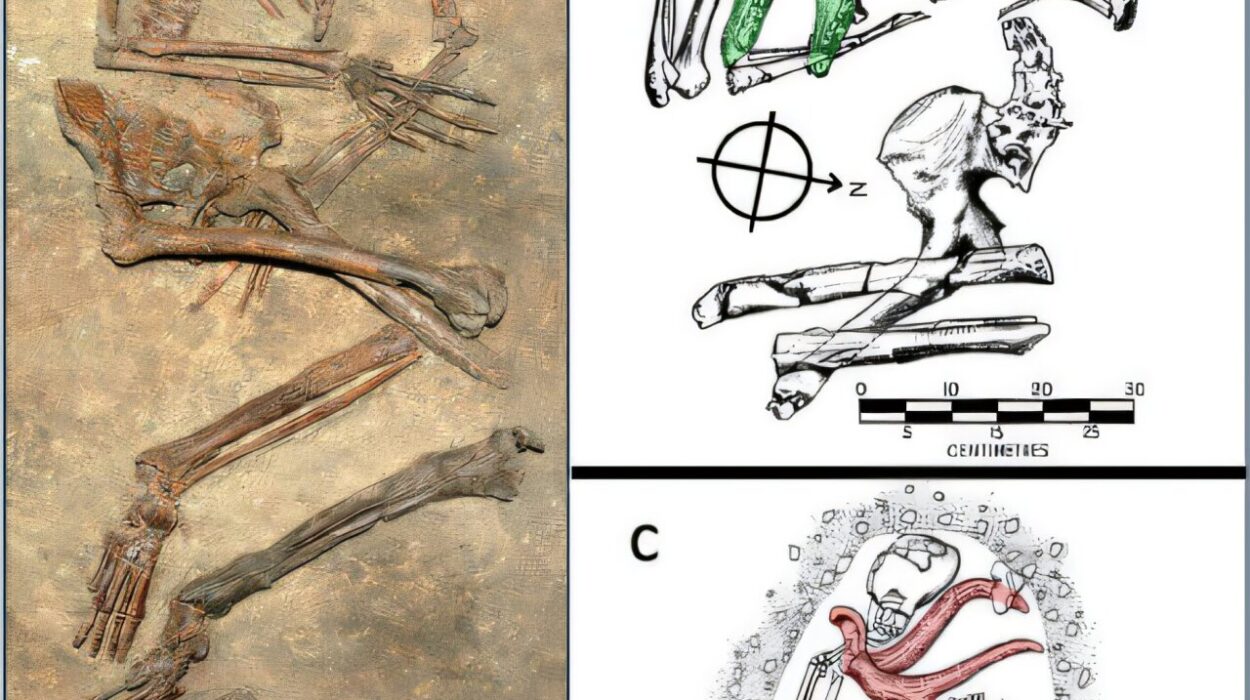

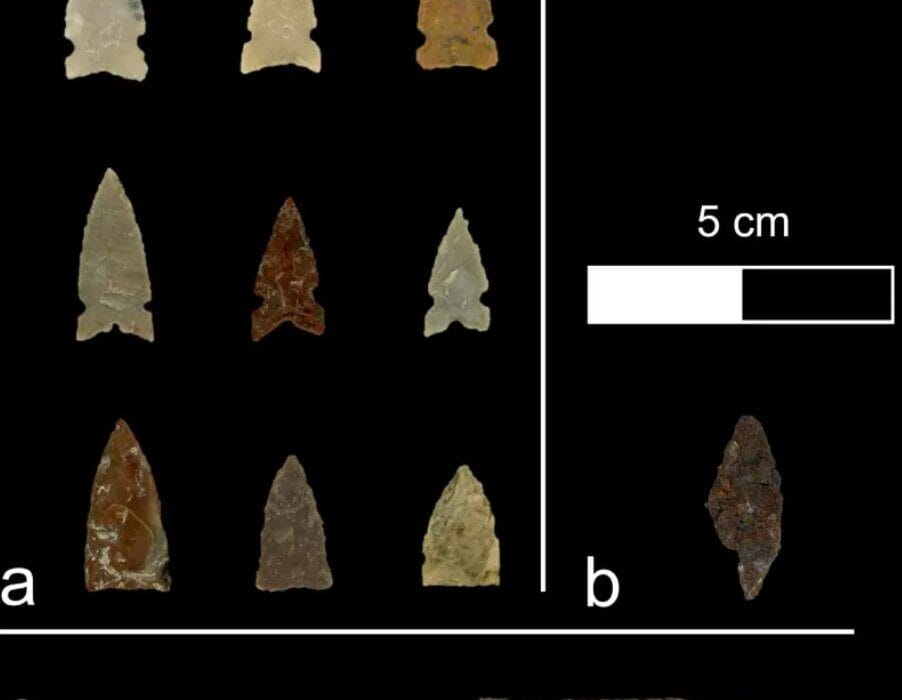

After its collection, the tooth was carefully and intentionally modified. Using tools of the time, early Copper Age craftspeople drilled precise holes and carved out pieces—perhaps to create pendants, charms, or ceremonial objects. These were not random marks of decay or marine erosion. They were the signatures of intelligent, deliberate artisanship.

But what is most astonishing is what happened next.

Rather than discarding the leftover tooth or keeping it in continued use, the people of Valencina buried it again—this time not in sand, but in the ground of their village. In doing so, they treated it as something more than material. Perhaps it had fulfilled its symbolic role. Perhaps it was being returned, like a sacred object whose purpose had been served.

As it lay entombed in the dry earth, the roots and soil added further erosion, wearing the tooth down and sealing it in a hardened crust of time. It remained untouched until 21st-century archaeologists uncovered it millennia later.

An Ivory of the Sea

Ivory has always captivated human cultures. Its combination of beauty, strength, and rarity has made it a material of choice for ornaments, musical instruments, and sacred objects. From mammoth tusks in Ice Age caves to elephant ivory in Neolithic Europe, humans have carved symbols of life, death, and power into this enduring material for nearly 40,000 years.

But marine ivory—like that from whales—has been far less studied in prehistoric contexts.

The Valencina sperm whale tooth challenges that gap. It is a reminder that ancient societies didn’t only draw meaning from the land—they were in deep communion with the sea as well.

“The sea was not a void to these people. It was an active part of their world,” said the study’s lead authors. “This artifact shows us how coastal resources—both physical and symbolic—flowed into the interior and into daily life and belief.”

A New Chapter in Prehistoric Archaeology

To unpack the story hidden in the tooth, researchers brought together the disciplines of archaeology, paleontology, geology, and cutting-edge technology. Through taphonomic analysis—the study of how remains decay and fossilize—they reconstructed the sequence of events from the whale’s death to its burial at Valencina.

The team also created high-resolution 3D models of the specimen, capturing every detail without risking damage. These scans revealed features too subtle to notice with the naked eye: tool marks with clearly non-natural origins, cut edges, and modified surfaces that reflected the practiced hands of prehistoric craftspeople.

This scientific rigor helps bridge two seemingly disparate worlds—the wild, churning ocean where the whale once swam, and the dry, structured earth of a complex human settlement.

A Portal Into Ancient Beliefs

Why go to the trouble of retrieving, transporting, modifying, and then reburying a single tooth from a marine giant?

The answer likely lies in belief and symbolism. In many early cultures, whales and other large sea creatures were viewed as mythical, powerful beings. To possess a part of such an animal could have been spiritually significant—an emblem of protection, transformation, or cosmic connection.

Even in the absence of written records, actions speak loudly. The reverence shown toward this whale tooth mirrors the ceremonial treatment of other prized objects found at Valencina—such as ornate blades, amber beads, and elaborate burials.

Together, these artifacts tell of a people deeply invested in the material and spiritual dimensions of their world. They carved stories into bones and ivory. They turned the remnants of death into objects of meaning.

Echoes from the Ocean

The sperm whale tooth now rests not beneath layers of earth, but in the careful hands of researchers who see it for what it is: not just an artifact, but a message. It speaks of oceans long passed, of cultural values written not in ink but in craft, and of a profound human impulse to find meaning in the extraordinary.

For modern scientists, the find is a spark—a reminder that history is never fully written, only discovered.

“This one object has the power to shift our understanding of prehistoric Iberia,” the research team noted. “It reminds us that even then, people were connected to vast and complex worlds, stretching far beyond what we can see today.”

And somewhere off the ancient coast, where the sun glints off the sea and the waves roll as they did five thousand years ago, perhaps another story still waits to be found.

Reference: Samuel Ramírez-Cruzado Aguilar-Galindo et al, From the jaws of the “Leviathan”: A sperm whale tooth from the Valencina Copper Age Megasite, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0323773