In the quiet prairie lands near the North Platte River in Casper, Wyoming, a forgotten archaeological treasure has come back into the light. Nearly half a century after the initial excavation of the River Bend site—officially known as 48NA202—a team led by Dr. Spencer Pelton has conducted the first comprehensive analysis of the vast artifact collection recovered there.

The findings, recently published in Plains Anthropologist, tell a story of cultural transformation, resilience, and artistry at a time when Indigenous life on the Plains was undergoing profound change. Dated to roughly AD 1700–1750, the River Bend site captures a pivotal moment—just after Euro-American contact began altering Indigenous societies, but before those changes completely took root. What emerges is a portrait of Native ingenuity and identity, etched into shell beads, bone tools, and elk ivory pendants.

The Adornment Archive That Time Almost Forgot

The River Bend site was originally excavated in the 1970s during a salvage operation ahead of construction. While archaeologists at the time uncovered hundreds of square meters, an estimated 75% of the original site was destroyed during construction. Much of what was saved was then shelved and forgotten. For decades, thousands of artifacts—many unlabeled or loosely catalogued—sat in lab drawers and cardboard boxes.

“It wasn’t in horrible shape,” says Dr. Pelton, Wyoming’s State Archaeologist, “but there were labels missing from artifacts, field notes missing or undiscovered… collections research always requires doing some ‘archaeology of archaeology’ to piece things back together.”

Despite these obstacles, the research team was able to reconstruct a vivid picture of the site and its occupants. Their efforts have revealed the River Bend site as one of the richest Indigenous adornment assemblages ever found in Wyoming, with over 5,000 artifacts made of bone, shell, stone, ocher, antler, and metal.

In the Middle of Two Worlds

What makes River Bend exceptional is its timing. It sits at the intersection of two epochs—after the first waves of European influence reached the American West, but before these influences had fully transformed Indigenous lifeways. This period is rarely captured in the archaeological record, which often skews either to pre-contact sites or to later historical ones shaped by trade and colonization.

Carolyn Buff, a co-author of the study and one of the original excavators in the 1970s, had initially identified possible links to the Eastern Shoshone people based on artifact types common to that culture. These included tri-notched arrow points, steatite bowls, and “teshoas”—split cobbles used to soften hides. Though not definitive, these cultural fingerprints suggest that the site’s inhabitants were likely part of or closely connected to the Shoshone world.

“Steatite is commonly found in sites in the Shoshone heartland of western Wyoming,” explains Dr. Pelton, “and teshoas are a uniquely Shoshone artifact. The combination of these items, especially alongside the arrow point styles, provided good clues—but other groups may have used these too.”

Still, the overall pattern supports a Shoshone affiliation. And the adornment artifacts recovered from River Bend add compelling layers to this interpretation.

Adornment as Identity: A Rich Material Language

For the Indigenous peoples of the Plains, adornment was far more than decoration—it was communication. Beads, pendants, and other body ornaments conveyed identity, status, family ties, spiritual beliefs, and individual achievements. The adornments recovered from River Bend reflect a nuanced interplay of tradition and adaptation.

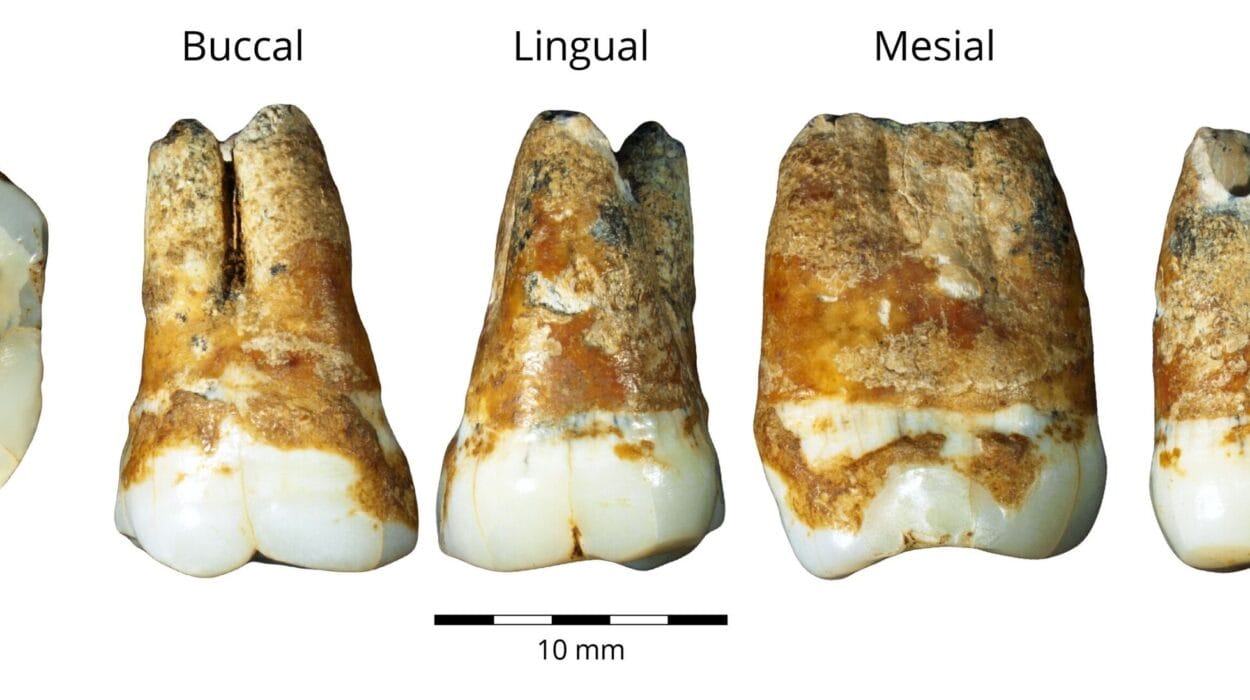

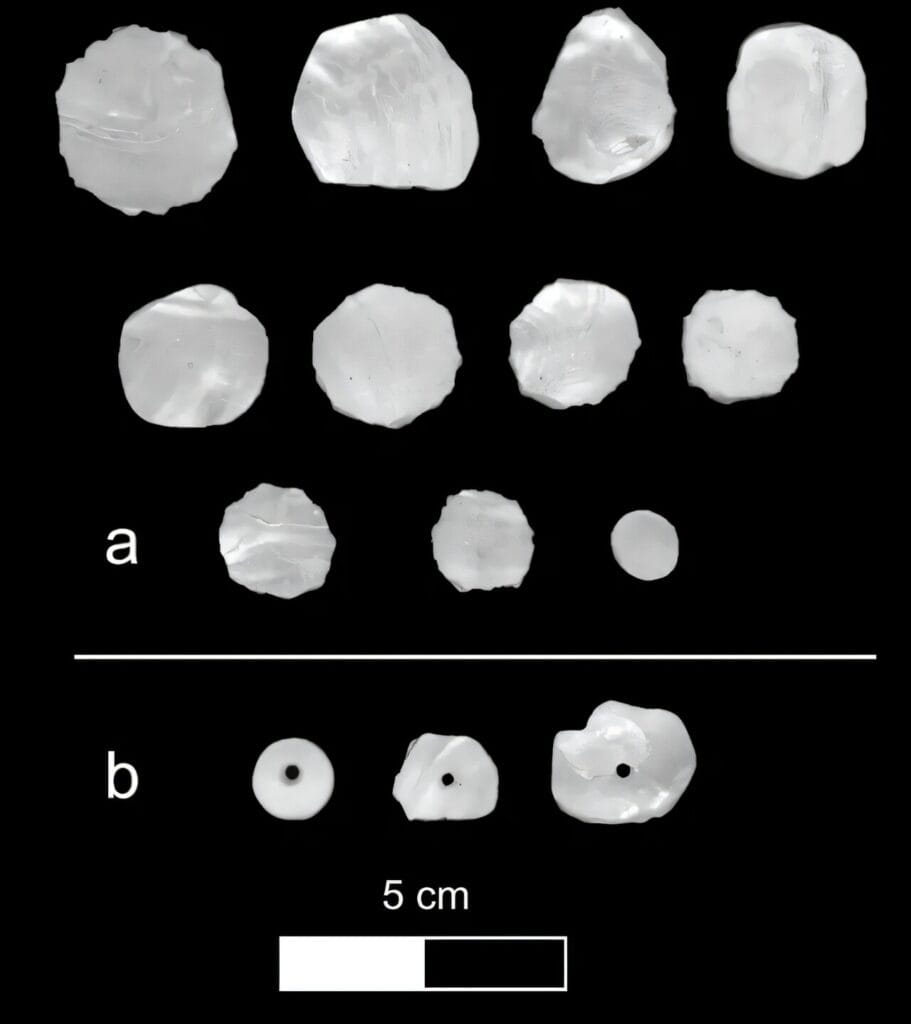

Shell disk beads—often associated with ceremonial or high-status uses—were found in abundance. These beads, typically strung into necklaces or sewn onto garments, have been documented at burial sites across the Plains, adorning the necks, wrists, and ankles of the deceased.

Even more striking was the discovery of Olivella shell beads. These tiny marine shells, native to the Pacific coast, had to be traded over vast distances before reaching the Wyoming plains. Their presence at River Bend confirms that the site’s inhabitants participated in wide-reaching trade networks long before the railroads or wagon trails came.

“The recovery of Olivella shells speaks to a long tradition of long-distance exchange,” says Dr. Pelton. “We know from later historical records that these were used as necklaces, earrings, and shirt decorations, and there’s no reason to think they didn’t serve similar purposes before contact.”

Pendants Through Time: Shifting Aesthetics and Materials

Another intriguing discovery from the River Bend site was the co-occurrence of shell pendants and elk ivory pendants—two adornment types with very different historical trajectories. Shell pendants, which date back more than 1,500 years in the archaeological record, appear to decline in visibility in later historical imagery.

Only a handful of early 19th-century paintings—most notably by Swiss artist Karl Bodmer—depict Indigenous people wearing shell pendants. By contrast, elk ivory pendants become increasingly common in photographs, explorer accounts, and trade records of the later 19th century.

“It looks like there’s a transition taking place in adornment preferences,” Pelton notes. “Shell pendants gradually disappear from the visible record, while elk ivory takes their place. River Bend helps us see that turning point happening in real time.”

This shift wasn’t just aesthetic—it was practical. Elk ivory was easier to obtain locally than marine shell, and it may have taken on new symbolic value as social structures evolved. The transition also suggests changing values, tastes, and perhaps even ceremonial practices among the Plains tribes in the wake of Euro-American contact.

Tools of Transformation: The Rise of Metal

Among the most significant findings was the discovery of metal awls, which likely played a role in bead and pendant production. Before contact, Indigenous peoples fashioned awls from bone or stone. Metal awls—easier to use, longer-lasting, and sharper—were among the earliest European trade goods to be adopted.

“We haven’t seen awls like this at other sites from the same period,” Pelton explains. “But they seem to be among the first types of metal tools to appear at early contact sites. They quickly replaced older technologies, which had been used for thousands of years.”

These utilitarian tools—along with metal knives, kettles, needles, and axes—offered tangible improvements in daily life. Their early adoption reflects the practical needs of the community, not just their openness to novelty. Tools that could be integrated into existing lifeways were the first to cross the cultural threshold.

At River Bend, the presence of metal awls likely helped artisans work more quickly and effectively, especially with abundant materials like shell. This small technological change had ripple effects, possibly increasing the production and distribution of adornment items, reinforcing social networks, and shaping identity practices.

A Rare Window into Cultural Continuity and Change

In many ways, the River Bend site is a microcosm of broader patterns in early post-contact Indigenous life. It reveals how Plains cultures navigated profound changes—not by abandoning their traditions, but by weaving new materials into existing frameworks.

Adornments continued to signal social standing, tribal affiliation, and spiritual belief. But the beads and pendants themselves began to reflect shifting material conditions—iron tools, marine shells, new aesthetics. Rather than seeing this as a loss of tradition, Pelton and his team interpret it as evidence of dynamic cultural resilience.

“This wasn’t a sudden break with the past,” says Pelton. “It was a process—measured, adaptive, and deeply human. The people at River Bend were choosing what to adopt, what to keep, and what to change. They were shaping their identity just as much as they were shaping bone, shell, and stone.”

Reviving the Forgotten Voices of the Plains

The story of River Bend is not just about archaeology—it’s about memory. For decades, the artifacts sat mostly untouched, disconnected from their deeper meanings. Dr. Pelton’s team has reanimated those voices, giving new life to objects that once held great personal and communal value.

Their work also highlights the importance of curating and revisiting old collections. In an age when archaeological excavation is often constrained by development and climate threats, the laboratories and repositories of the past may hold the keys to untold stories.

In the case of River Bend, those stories include the first glimmers of trade-driven change, the persistence of cultural markers, and the quiet dignity of a people crafting beauty from bone and bead at the edge of upheaval.

As Dr. Pelton puts it, “Sites like River Bend remind us that Indigenous history isn’t just about survival—it’s about continuity, creativity, and the choices communities made as they faced an unfamiliar future. And it’s our job as archaeologists to make sure those choices are remembered.”

More information: Spencer R. Pelton et al, Early eighteenth century plains Indian adornment at the River Bend Site, Wyoming, Plains Anthropologist (2025). DOI: 10.1080/00320447.2025.2530336