Baishiya Karst Cave, Tibetan Plateau — High above the clouds, in a forbidding limestone cave perched 3,280 meters (10,761 feet) above sea level, scientists have uncovered fresh clues to one of humanity’s most enigmatic relatives. In this wind-scoured pocket of the Tibetan Plateau, new research has unearthed the ancient bone of a long-lost human species—the Denisovans—offering tantalizing insights into how these prehistoric people not only survived, but flourished, in some of Earth’s harshest conditions for over 160,000 years.

The findings, published this week in the prestigious journal Nature, shine new light on a population that remains shrouded in mystery. The Denisovans—an extinct branch of the human family tree—once walked alongside Neanderthals and modern humans, but left behind only a whisper of evidence: a few teeth, a pinky bone, and now, remarkably, a rib from a cave dwelling nearly three kilometers above sea level.

In this vast, wind-lashed wilderness of snow and rock, the bones tell a quiet but powerful story.

A Ghost Species Emerging from the Shadows

The Denisovans have haunted the annals of paleoanthropology like ghosts—present in our DNA, but elusive in the fossil record. First identified from a fragmentary finger bone in a Siberian cave in 2010, they were recognized not through their skulls or skeletons, but through their genes. They are the ghost cousins of Homo sapiens, who shared Earth—and even beds—with both modern humans and Neanderthals.

Despite their shared history with us, Denisovan fossils are vanishingly rare. To date, only two known sites have yielded physical remains. One is the Denisova Cave in Siberia. The other, more recently explored, is Baishiya Karst Cave in China’s Ganjia Basin, where the new research has now turned up a breakthrough: the first confirmed rib bone of a Denisovan individual, found among a chaotic jumble of over 2,500 animal bones.

“Each new Denisovan fossil helps us fill in enormous blanks in our understanding of this population,” said Dr. Geoff Smith, a zooarchaeologist at the University of Reading and a co-author of the study. “We’re beginning to see not just who they were, but how they lived—and thrived—in one of the most extreme environments on Earth.”

Survival in the Sky: Life on the Roof of the World

The Tibetan Plateau is not a forgiving place. It is a world of thin air, bitter winters, and minimal vegetation—a landscape more suited to snow leopards than to humans. And yet, the new evidence shows that Denisovans endured here not for a fleeting period, but for tens of thousands of years, from roughly 200,000 to 40,000 years ago.

How did they manage it?

The key may lie in their adaptability—and their diet.

The research team, which included experts from Lanzhou University in China, the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, employed a cutting-edge technique known as Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (ZooMS). This method detects subtle differences in bone collagen to identify animal species, even when the bones themselves are broken beyond recognition.

Using ZooMS, the researchers analyzed over 2,500 bone fragments from Baishiya Karst Cave and identified the remains of a diverse array of animals that Denisovans hunted and consumed. These included blue sheep (bharal), wild yaks, horses, and even the extinct woolly rhinoceros. There were also signs of marmots, birds, and spotted hyenas—evidence of a rich and varied diet.

“These bones tell us about a highly adaptable group of people who could exploit the full range of ecological resources available to them,” said Dr. Huan Xia of Lanzhou University. “They were not just surviving—they were mastering their environment.”

Bone Tools and Butchery: A Glimpse into Daily Life

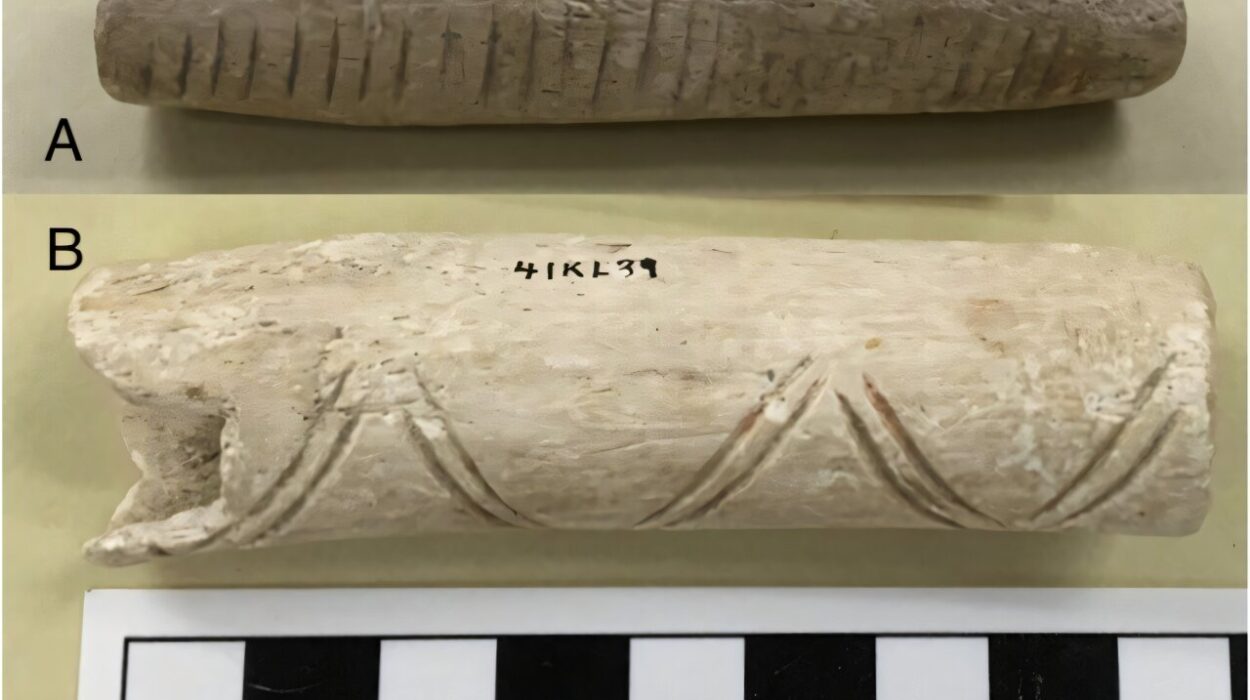

The study goes beyond diet to examine the behaviors and tools of Denisovans. Careful examination of the animal bones revealed cut marks, fractures consistent with marrow extraction, and signs of intentional breakage. Some bones were even shaped and used as tools.

These are not the remnants of random scavenging. They tell the story of systematic hunting, careful butchery, and craftsmanship—of a people who understood both their prey and their tools.

“It’s easy to forget that these people were not primitive brutes,” said Dr. Jian Wang of Lanzhou University. “They were intelligent, capable, and fully human in their behaviors, even if they belonged to a distinct lineage.”

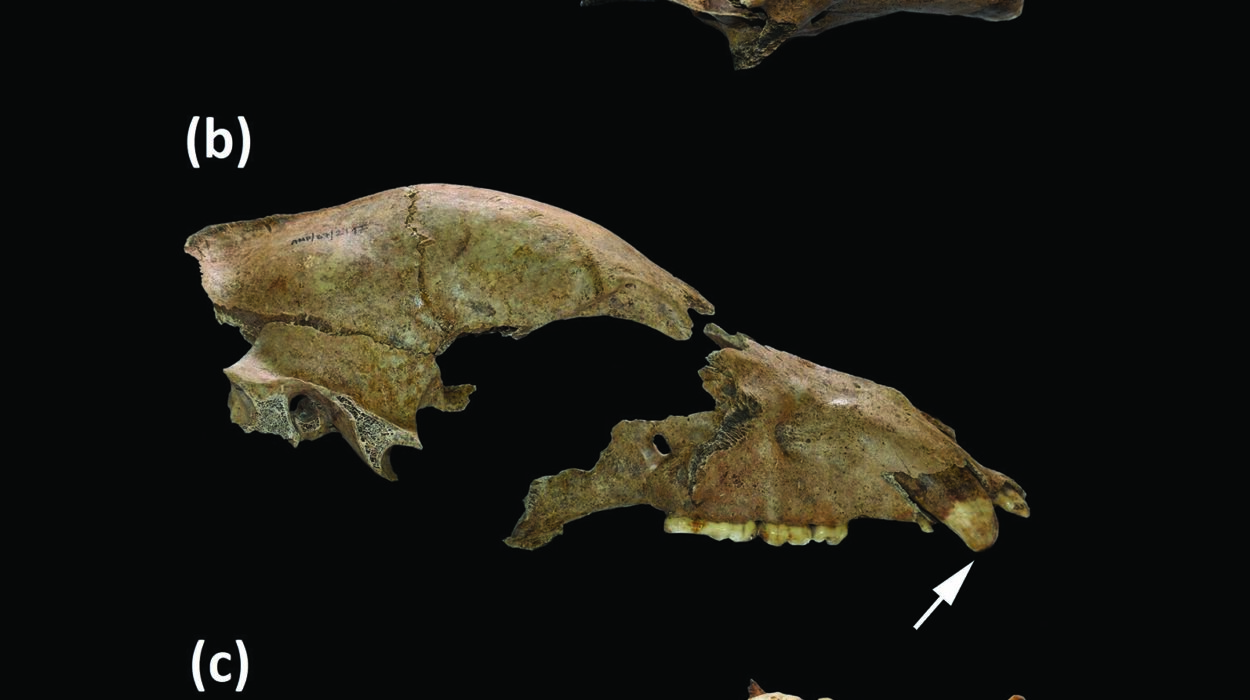

A Rib Through Time: Clues from the Fossil Record

The most thrilling discovery of the new study is the identification of a rib bone from a Denisovan individual. This is only the second Denisovan fossil confirmed at Baishiya Cave, after a jawbone found there in 2010.

The rib was found in a sediment layer dated to between 48,000 and 32,000 years ago—a critical window in human history. This was a time when Homo sapiens were rapidly expanding across Eurasia. It now appears that Denisovans were not only still alive at that time, but were thriving in the high-altitude sanctuary of the Tibetan Plateau.

“Finding this rib is a major step forward,” said Dr. Frido Welker, a molecular anthropologist at the University of Copenhagen and co-author of the study. “It’s direct physical evidence that Denisovans persisted here far longer than we might have assumed.”

The Denisovan Puzzle: Why Did They Disappear?

While the discovery paints a vivid picture of Denisovan life, it also raises haunting questions.

Why did this capable, resilient population vanish?

The researchers note that the Ganjia Basin, where Baishiya Cave is located, offered a relatively stable microclimate, even as the broader world experienced massive fluctuations between glacial and interglacial periods. This refuge may have sheltered Denisovans through some of the most severe cold snaps of the Pleistocene era.

And yet, at some point after 40,000 years ago, they disappeared. Did they die out? Were they absorbed into other human populations? Or did they retreat even further into the mountains, leaving only their DNA behind?

We know from genetic studies that many modern human populations, particularly in Asia and Oceania, carry fragments of Denisovan DNA. In fact, some genes inherited from Denisovans are believed to help modern Tibetans survive in high altitudes—a lingering echo of their ancient neighbors.

“The question now arises when and why these Denisovans on the Tibetan Plateau went extinct,” Dr. Welker said. “We have the who, and some of the how. Now we must find the why.”

A Glimpse into the Forgotten Past

This study is more than a catalog of bones and dates. It is a window into a world long buried beneath dust and time—a world where an ancient people once hunted in the thin air, where fires burned in a cave high above the clouds, where human voices echoed off limestone walls thousands of years before history began.

As the snow falls once more on the Tibetan Plateau and the wind howls across its barren ridges, the bones speak. They speak of survival, of skill, of life and mystery.

And in their silent way, they remind us that the human story is far older—and far stranger—than we ever imagined.

Reference: Frido Welker, Middle and Late Pleistocene Denisovan subsistence at Baishiya Karst Cave, Nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07612-9. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-07612-9