More than 2,800 years ago, the people of Jerusalem lived in a world far harsher and more unpredictable than the one most of us know today. In the 9th century BCE, this Iron Age city was no glittering capital; it was a fortified stronghold perched on the ridge of the Judean hills, dependent on a single spring—the Gihon—for its survival. Life here revolved around water. When it flowed, the city prospered. When drought struck, the city trembled.

And drought did strike. Archaeological and climate records reveal years of parched skies, broken by sudden and violent flash floods that washed away precious soil and crops. The land was caught between extremes: too little rain when it was needed most, too much when the ground could no longer absorb it. For a city that aspired to greatness, such unpredictability was dangerous.

This was not just a matter of comfort—it was survival. Without reliable water, there could be no agriculture, no livestock, no city strong enough to resist enemies. For Jerusalem, climate change was not an abstract concept debated in royal courts; it was a daily, existential threat.

A Royal Response to Crisis

Faced with this challenge, the rulers of Judah—most likely King Jehoash or his successor Amaziah—chose a bold path. They would not surrender to nature’s whims. They would build.

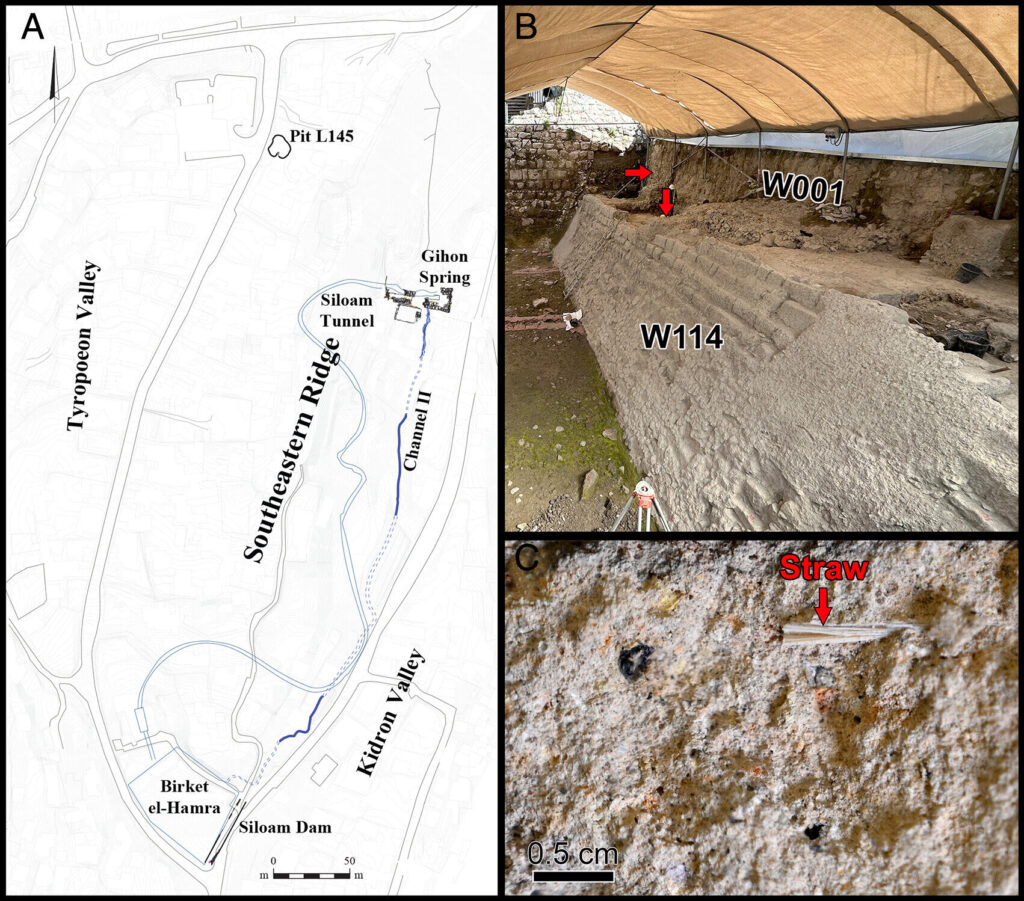

The solution they conceived was ambitious, perhaps even audacious: fortify the city’s only perennial spring and redirect its waters into a massive man-made reservoir. This was no ordinary cistern dug in haste, but a monumental public works project: the Siloam Dam.

By capturing the Gihon Spring and channeling its flow into the newly created Siloam Pool, the city could store water through dry months. The reservoir would also collect rainwater, turning unpredictable storms into an asset rather than a curse. For the first time, Jerusalem’s survival would not be tied so precariously to the moods of the heavens.

This project was not just an engineering feat—it was a statement. It announced that Jerusalem was not a fragile hilltop settlement but a rising city with the foresight and power to shape its destiny.

Rediscovering an Ancient Masterpiece

For centuries, the story of the Siloam Dam lingered in half-remembered fragments of text and stone. The Book of Kings and the Chronicles of Judah mention great building projects, but archaeology has only slowly pieced together the details.

Now, thanks to a groundbreaking study led by Dr. Johanna Regev and Prof. Elisabetta Boaretto of the Weizmann Institute of Science, in collaboration with the Israel Antiquities Authority, this ancient story has been illuminated with rare precision.

The team used cutting-edge microarchaeological techniques and advanced radiocarbon dating on samples of straw and tiny charred twigs trapped within the dam’s mortar during its construction. These seemingly fragile remnants turned out to be time capsules, preserving the moment of building itself.

From them, the researchers established with remarkable accuracy that the Siloam Dam was built between 805 and 795 BCE—a narrow, decade-long window almost unheard of in the dating of ancient structures. For historians and archaeologists, such clarity is gold. It ties the dam directly to the reign of Judah’s early kings and anchors the engineering project firmly in the city’s 9th-century BCE struggle against climate stress.

Climate Clues Written in Stone and Soil

But dating alone was not enough. To truly understand why this massive project was undertaken, the researchers turned to another source: climate records.

They drew on multiple natural archives—Dead Sea drill cores, which reveal changes in rainfall and water levels over millennia; stalagmites from Soreq Cave, whose growth rings record precipitation patterns; and even records of solar activity, traced through radioactive isotopes formed in the atmosphere.

Together, these sources painted a clear picture: the 9th century BCE was a time of volatile weather in the Levant. Long droughts starved the land, and sudden floods wreaked havoc. In this context, the Siloam Dam emerges not just as a feat of urban planning, but as an act of survival against a changing climate.

As the researchers themselves put it, this was evidence of “sweeping urban planning” in Jerusalem far earlier than many had imagined. It reveals a city that was already learning to adapt, already flexing its ingenuity against the forces of nature.

Human Ingenuity in the Face of Uncertainty

What makes the story of the Siloam Dam so powerful is not just its stones or its scale, but its humanity. We see here a city confronted by the same eternal struggle that faces us today: how to survive in a world where the climate does not play by predictable rules.

The rulers of Judah could have done nothing, could have watched their people grow weaker with every passing drought. Instead, they mobilized laborers, artisans, and engineers to build a solution that would safeguard their community for generations. The dam was not only stone and mortar—it was resilience made tangible.

It is easy to think of ancient people as passive victims of their environment. Yet the Siloam Dam reminds us that they, too, innovated. They, too, adapted. They, too, saw the challenge of climate and chose to fight back with vision and skill.

A Legacy of Water and Power

The construction of the Siloam Dam was not merely about survival. It was also about identity. Water control was a visible symbol of power, an assertion that Jerusalem was not a minor outpost but a city capable of commanding resources and organizing large-scale projects.

In ancient societies, the ability to manage water was often tied to political legitimacy. Just as Egyptian pharaohs built canals to tame the Nile, and Mesopotamian kings raised levees to master the Tigris and Euphrates, so too did the kings of Judah strengthen their rule by mastering Jerusalem’s water.

The Siloam Dam and Pool served not only practical needs but civic ones, becoming gathering places where people met, drew water, and reinforced their shared identity as citizens of a strong and enduring city.

Lessons for Today

There is a haunting familiarity to this story. Almost three millennia later, humanity is once again facing climate instability. Droughts grow longer, floods more severe, water scarcer in many regions. Like the people of Jerusalem, we find ourselves at a crossroads where survival depends not just on endurance but on ingenuity.

The Siloam Dam reminds us that adaptation is not new. Human beings have always met the challenge of a changing climate with creativity and determination. What has changed is the scale. While ancient Jerusalem needed to safeguard a single city, we now face the task of safeguarding an entire planet.

The lesson is clear: resilience requires foresight. The kings of Judah acted not in desperation but in planning, investing in infrastructure before disaster overwhelmed them. If they could do so with stone, mortar, and hand tools, then we, with our technology and knowledge, must ask ourselves—what excuse do we have not to act?

Conclusion: Stones that Still Speak

The stones of the Siloam Dam may lie weathered and silent today, but thanks to science, they have found their voice again. They tell us of a time when a city under threat rose to meet the challenge with vision and courage. They tell us that climate change is not only a modern concern but an ancient story, woven through human history.

Most of all, they tell us that resilience is possible. The people of Iron Age Jerusalem did not surrender to thirst. They built, they adapted, they endured. Their dam was more than a reservoir of water—it was a reservoir of hope.

And as we face our own uncertain climate future, perhaps we too can draw strength from their example, letting their ancient ingenuity inspire our modern resolve.

More information: Johanna Regev et al, Radiocarbon dating of Jerusalem’s Siloam Dam links climate data and major waterworks, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2510396122