In the shadows of Egypt’s towering pyramids and monumental temples lies another great civilization, often overlooked yet equally remarkable: the Kingdom of Kush in ancient Nubia. Stretching along the fertile banks of the Nile in what is today southern Egypt and northern Sudan, Nubia was once the seat of power for rulers who dared to rival, and at times dominate, the mighty pharaohs of Egypt. For thousands of years, Nubia thrived as a land of warriors, traders, and kings—an African powerhouse that shaped the course of history in ways often forgotten by mainstream narratives.

To tell the story of ancient Nubia is to restore a chapter of humanity’s heritage. It is a tale of resilience and innovation, of ambition and conquest, of faith and artistry. It is the story of the Kushite kings who rose from a land dismissed as Egypt’s “southern frontier” to rule as Pharaohs themselves, leaving behind pyramids, temples, and legends that endure to this day.

Nubia: Geography and the Birth of Civilization

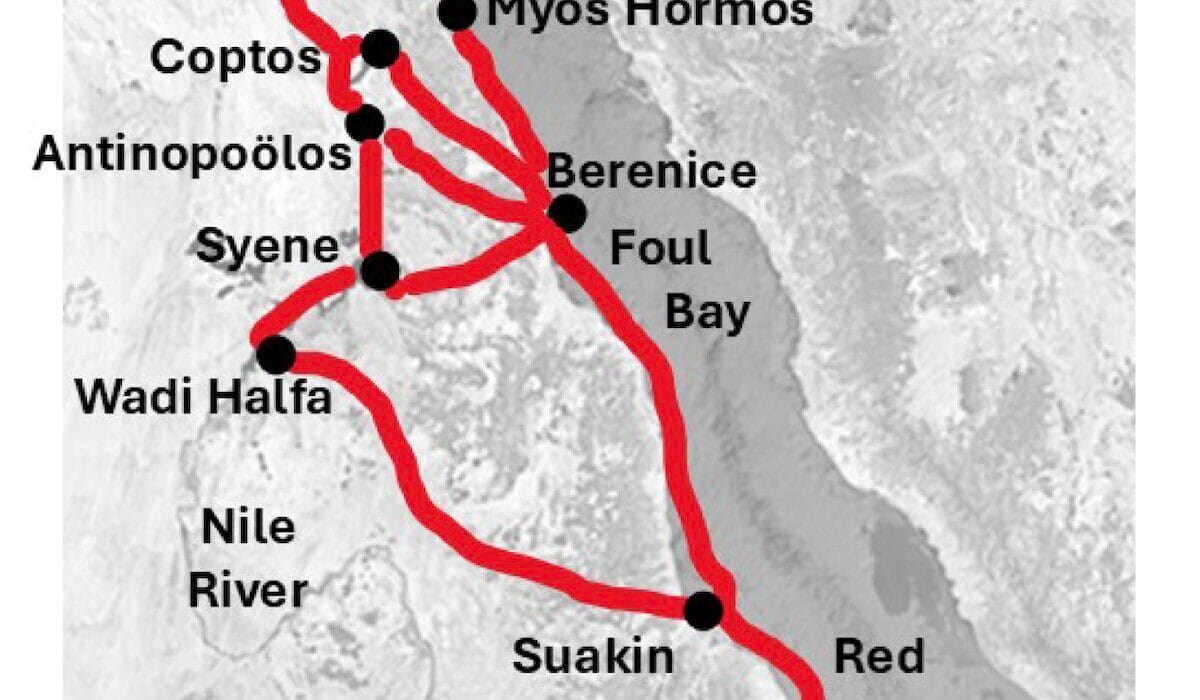

The lifeline of Nubia was the Nile. Flowing northward from the heart of Africa, the Nile carved a narrow green ribbon through desert landscapes, bringing life to an otherwise harsh environment. Nubia, whose name is thought to derive from the ancient Egyptian word nbw meaning “gold,” was rich in natural resources. Gold mines, ivory, ebony, exotic animals, and precious stones made it a coveted land for trade and conquest.

The geography of Nubia was distinct. It was divided by six cataracts—rocky stretches of the Nile that created natural barriers and shaped the political landscape. Lower Nubia lay between the First and Second Cataracts, while Upper Nubia extended further south. This division influenced the rise of kingdoms and the flow of culture between Nubia, Egypt, and sub-Saharan Africa.

Archaeological evidence reveals that Nubia was home to advanced societies as early as 3500 BCE. These early Nubian cultures developed complex pottery styles, practiced cattle herding, and established trade routes. They were not passive recipients of Egyptian culture but active participants in a dynamic exchange, blending African traditions with Mediterranean influences.

Nubia and Egypt: Rivals and Partners

The relationship between Nubia and Egypt was never simple. It was a mix of rivalry, warfare, trade, and cultural exchange. To the Egyptians, Nubia was both a source of wealth and a threat. Egyptian pharaohs launched military campaigns to control Nubia’s resources, building fortresses along the Nile. At times, Nubia was absorbed into the Egyptian empire; at other times, it remained fiercely independent.

But the influence flowed both ways. Nubians served in Egyptian armies, traded goods, and even adopted aspects of Egyptian religion and art. Nubian gods like Apedemak, a lion-headed war deity, coexisted with Egyptian deities. Over centuries, Nubians mastered the art of statecraft, learning from their northern neighbors while preserving their own identity. This long and complex relationship set the stage for one of history’s most dramatic reversals of power.

The Rise of the Kingdom of Kush

Around 2000 BCE, as Egypt’s Middle Kingdom expanded southward, Nubia witnessed the rise of powerful chiefdoms. By 1700 BCE, the Kingdom of Kush emerged in Upper Nubia with its capital at Kerma. Kerma was one of Africa’s earliest urban centers, boasting massive mudbrick structures, palaces, and temples. Archaeologists have uncovered enormous burial mounds filled with treasures, cattle, and even human sacrifices, reflecting the wealth and authority of Kushite kings.

Kerma’s rulers were formidable. They built an empire that rivaled Egypt, at times controlling vast stretches of the Nile valley. Egyptian records speak of Kushite kings as “vile enemies,” yet also as indispensable trade partners. Kerma thrived for centuries until Egypt, under the New Kingdom, launched a massive conquest around 1500 BCE, incorporating Nubia into its empire.

For centuries thereafter, Nubia was ruled by Egyptian governors. Temples to Amun and other gods rose in Nubian cities. Egyptian became the language of administration, and hieroglyphs adorned local monuments. Yet beneath this surface, Nubian culture endured, waiting for the moment it would rise again.

Napata and the Age of the Black Pharaohs

That moment came in the 8th century BCE, when Egypt itself was weakened by internal strife and foreign invasions. In Nubia, a new capital had risen at Napata, near the sacred mountain of Jebel Barkal. Here, Kushite kings embraced both Nubian traditions and Egyptian religious ideals, claiming divine sanction from the god Amun.

It was from Napata that a dynasty of Nubian kings marched north to claim Egypt itself. Led by King Piye (also known as Piankhi), the Kushites conquered Egypt around 730 BCE, establishing the 25th Dynasty. For nearly a century, Nubian pharaohs ruled as Egypt’s kings, uniting the Nile Valley from the Delta to the heart of Africa.

These rulers—Piye, Shabaka, Shebitku, Taharqa, and Tanutamani—are remembered as the “Black Pharaohs.” They restored Egypt’s crumbling temples, revived ancient traditions, and defended the land against foreign powers. King Taharqa, in particular, left a lasting mark, commissioning grand temples and engaging in fierce battles against the expanding Assyrian Empire.

The reign of the Black Pharaohs was a moment of glory, a time when Nubia not only equaled Egypt but ruled it. Their dynasty symbolized the fluidity of power and the shared destiny of the Nile civilizations. Yet their time was brief. By the 7th century BCE, the Assyrians drove them out of Egypt, forcing the Kushite kings to retreat to Nubia.

Meroë: A New Capital, A New Culture

Exiled from Egypt, the Kushite kingdom did not vanish—it transformed. Around 590 BCE, the capital shifted further south to Meroë, marking the beginning of a new era. Protected by distance from foreign invaders, Meroë flourished for nearly a thousand years as a center of trade, industry, and culture.

Meroë was renowned for its ironworking. Archaeological excavations reveal vast furnaces and slag heaps, evidence that the city was an industrial hub of ancient Africa. Its artisans produced tools, weapons, and ornaments that fueled both local prosperity and long-distance trade. Caravans carried goods across the Sahara, linking Meroë to Mediterranean, Arabian, and sub-Saharan networks.

Culturally, Meroë developed a unique identity. While Egyptian influences persisted, local traditions came to the forefront. The Meroitic script, one of Africa’s earliest written languages, emerged around 300 BCE, though it remains only partially deciphered today. Temples were dedicated not only to Egyptian gods like Amun but also to Nubian deities such as Apedemak, whose lion-headed statues symbolized strength and protection.

The rulers of Meroë built hundreds of pyramids—smaller and steeper than those of Egypt but no less striking. These pyramids, many still standing in the deserts of Sudan, testify to the wealth and spiritual devotion of the Kushite elite. Unlike the grand tombs of Egypt, Meroitic pyramids reflected a distinct African aesthetic, with chapels and carvings blending Egyptian, Nubian, and local motifs.

Women of Power: The Kandakes

One of the most remarkable features of Meroitic society was the prominence of powerful queens known as Kandakes (or Candaces). These royal women were not mere consorts but sovereign rulers who led armies, negotiated treaties, and shaped the destiny of their kingdom.

Classical historians recount tales of Kandakes who defied Roman emperors. Strabo and Pliny the Elder describe a queen—likely Amanirenas—who fought against Augustus’ legions in the 1st century BCE, forcing a peace treaty that favored Nubia. The Kandakes symbolize a tradition of female leadership that set Kush apart from many other ancient societies.

Their legacy lives on in art and inscriptions, where they are depicted as commanding, regal figures. In a world often dominated by patriarchal rule, the Kandakes stand as a testament to the unique role of women in Kushite politics and religion.

Religion and the Sacred Landscape

Religion was central to Nubian life. At Napata, the temple of Amun at Jebel Barkal served as a spiritual heart, where kings sought legitimacy through divine approval. Priests held immense power, and rituals reinforced the connection between ruler and god.

In Meroë, religious practices evolved. While Egyptian gods remained revered, local deities gained prominence. Apedemak, the lion-headed god, became a protector of kings and warriors. The blending of Egyptian and indigenous beliefs created a spiritual tapestry that reflected Nubia’s identity—rooted in Africa yet engaged with the wider world.

Temples, pyramids, and sacred sites dotted the Nubian landscape. These were not only centers of worship but also symbols of authority, binding communities together through shared faith. Even after the fall of Kush, these religious traditions echoed in the cultures that succeeded it.

Decline and the End of Kush

Like all great civilizations, the Kingdom of Kush eventually declined. By the 3rd century CE, shifting trade routes, overexploitation of resources, and pressure from neighboring powers weakened Meroë. The rise of the Kingdom of Aksum in present-day Ethiopia posed a formidable challenge.

Around 350 CE, Aksumite armies invaded Nubia, bringing an end to the Kushite kingdom. Meroë was abandoned, its once-bustling streets falling silent. The pyramids and temples, left to the sands, became ruins—testimonies of a vanished empire.

Yet the legacy of Kush endured. Its cultural influences spread across the Nile Valley and into sub-Saharan Africa. Its pyramids still rise against the desert sky, silent witnesses to a civilization that refused to be erased.

Rediscovering Nubia

For centuries, Nubia’s history was overshadowed by Egypt’s grandeur. Early European explorers dismissed Nubian ruins as mere imitations of Egyptian art. Only in recent decades have archaeologists and historians begun to fully appreciate the depth and uniqueness of Nubia’s contributions.

Excavations at Kerma, Napata, and Meroë have revealed cities, temples, and tombs that showcase Nubia’s creativity and independence. Advances in archaeology, including satellite imaging and DNA analysis, are uncovering new layers of the Nubian story. Scholars now recognize that Nubia was not a peripheral culture but a central player in the ancient world.

The rediscovery of Nubia is more than an academic pursuit. It is an act of restoring dignity to a civilization long denied its rightful place in history. It is a reminder that Africa has always been a cradle of innovation, power, and artistry.

The Legacy of the Kingdom of Kush

What, then, is the legacy of ancient Nubia? It is the story of a people who rose from the banks of the Nile to challenge empires and leave their own indelible mark on history. It is the legacy of the Black Pharaohs, who ruled both Nubia and Egypt, blending cultures into a shared civilization. It is the legacy of Meroë’s ironworkers, traders, and queens, who built a society that flourished for centuries.

Most of all, the legacy of Kush is a reminder of resilience. Despite conquests and decline, the spirit of Nubia endures in its monuments, in its art, and in the pride of the Sudanese people who live in its shadow today.

Conclusion: Remembering the Forgotten Kingdom

Ancient Nubia, the Kingdom of Kush, was never a footnote to Egyptian history—it was a civilization in its own right, with achievements that rivaled the greatest of the ancient world. Its kings ruled as pharaohs, its queens defied empires, and its artisans left behind a landscape of pyramids and temples unlike any other.

To remember Nubia is to broaden our vision of human history. It is to see Africa not as a silent background to Egypt and Mesopotamia but as a stage where powerful kingdoms rose, flourished, and transformed the world.

The sands of Sudan still conceal untold stories, waiting to be unearthed. And as archaeologists continue their work, the forgotten kingdom of Kush is being remembered once more—not as an echo of Egypt, but as a voice of Africa’s own grandeur, resilience, and creativity.