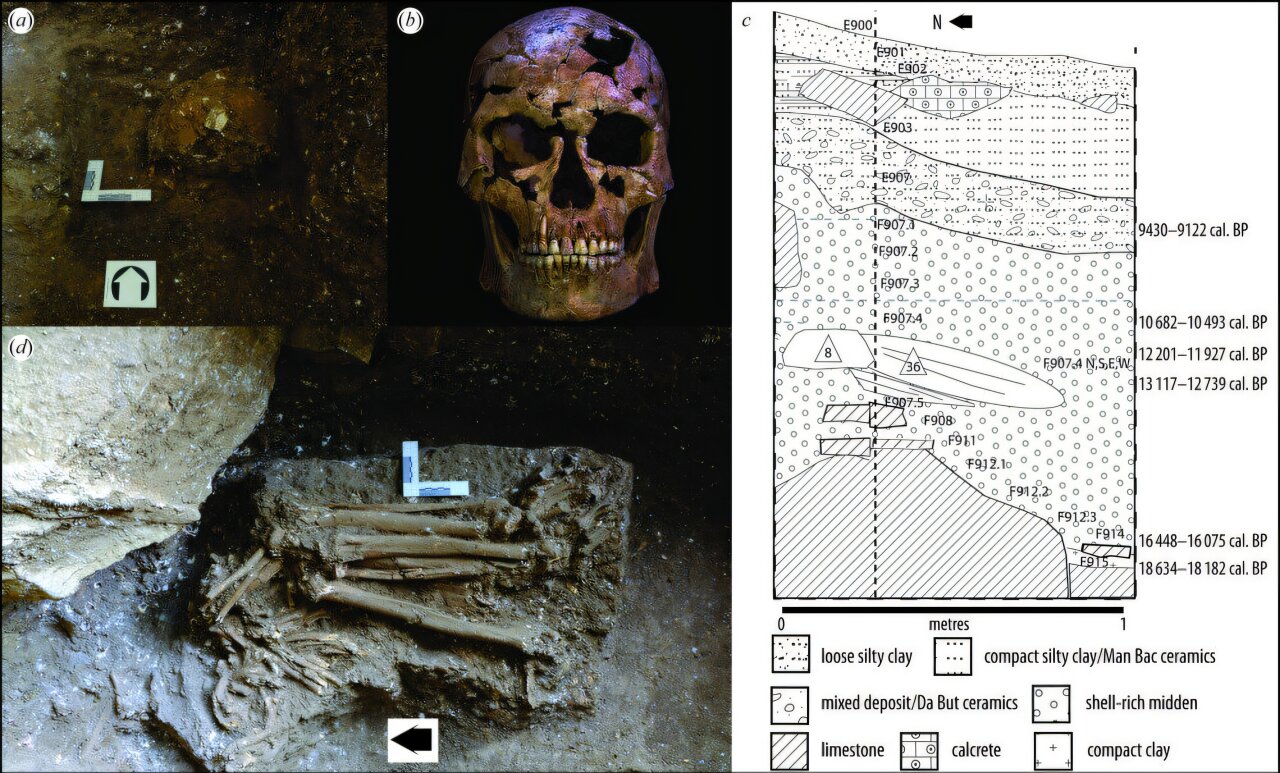

In 2018, deep within a limestone cave in northern Vietnam, archaeologists uncovered the nearly complete skeleton of a man who had walked the earth some 12,000 years ago. His remains, remarkably well-preserved, offered more than just a glimpse into prehistoric life. They told a story—one of survival, pain, and perhaps the earliest evidence of human conflict in Southeast Asia.

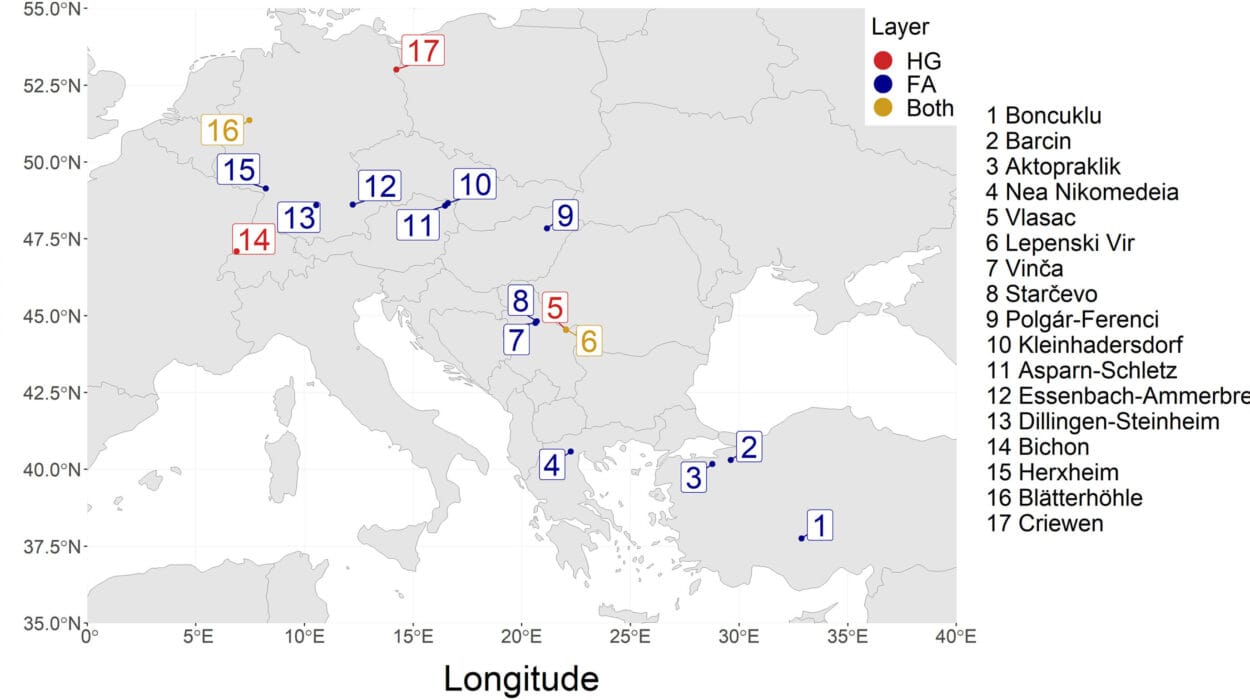

This man, now known as TBH1, lived during the late Pleistocene epoch, a time when human societies were small, mobile, and adapting to a world that was changing with the end of the Ice Age. He likely belonged to a hunter-gatherer group that depended on the forests, rivers, and rocky landscapes of the region for survival. Yet, his story reminds us that even in such ancient times, danger came not only from wild animals or harsh environments but also from other humans.

The Marks of a Violent Encounter

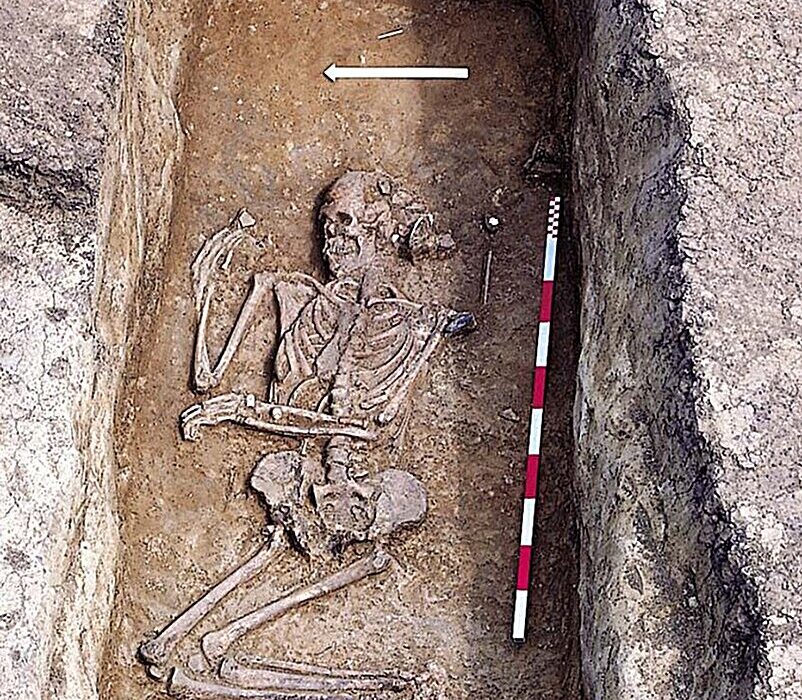

The skeleton of TBH1 was not just another archaeological find. It bore the unmistakable traces of violence. Researchers studying his remains discovered a fractured rib near his neck—one that carried clear signs of infection. Alongside it, lodged in the ancient bone, was a sharp fragment of quartz. The tiny, triangular stone was almost certainly part of an arrowhead or projectile.

This was no hunting accident. The location of the wound suggested that TBH1 had been deliberately targeted, struck by a weapon designed to pierce flesh and bone. Yet the arrow was not what killed him. The fracture showed evidence of healing gone wrong, including a pseudoarthrosis, or false joint, which develops only when a bone struggles to repair itself over time. Around the fracture, a draining cloaca had formed—an opening that allows pus to escape from an infection within the bone.

These signs revealed a haunting truth: TBH1 lived for weeks, perhaps months, after being struck. He endured the relentless pain of a festering wound in an age with no medicine, no antibiotics, and no relief beyond what nature could offer. Ultimately, it was not the violence itself but the infection that ended his life at around 35 years of age.

A Rare Glimpse into Prehistoric Lives

Human remains from this time period in Southeast Asia are incredibly rare. Bones decay quickly in tropical climates, leaving little behind for scientists to study. The preservation of TBH1 is therefore extraordinary—he is not only a man but also a messenger from a world long vanished.

His skeleton also carried another unusual detail: he had 25 ribs instead of the usual 24, a rare genetic variation present in less than 1% of the population today. Though this extra rib likely had no impact on his health, it made his remains distinctive and provided scientists with an even clearer picture of his anatomy.

Other injuries were present too. His skull had been crushed after death, likely the result of natural processes within the cave rather than violence. He also had a small ankle injury, but otherwise, his bones told the story of a man who had been healthy and strong—until the arrow struck.

The Oldest Evidence of Conflict?

What makes TBH1’s story so significant is not just his tragic end but what it reveals about human behavior in Southeast Asia thousands of years ago.

Christopher M. Stimpson, lead author of the study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, suggests that this case is the earliest known evidence of interpersonal violence in mainland Southeast Asia. The arrow wound and subsequent infection mark more than an individual tragedy—they point to the presence of conflict, hostility, and perhaps organized aggression among prehistoric communities.

Yet, caution is necessary. One skeleton cannot tell us how widespread such violence was. Was TBH1 an unfortunate victim of a rare clash, or was conflict a more common part of life than we realize? Only more discoveries—buried bones waiting in the soil of Southeast Asia—can provide the answers.

Life, Death, and Humanity in the Late Pleistocene

The death of TBH1 may seem remote, a fragment of prehistory far removed from our modern world. But his story is deeply human. It is the story of a man who suffered, who endured pain, and whose fate was shaped by the choices of another human hand that drew a bow and loosed an arrow.

His life also reminds us of the fragility of existence in ancient times. Without modern medicine, even a wound that might be easily treated today could spiral into a slow, agonizing death. Yet, his survival for weeks or months after the injury also points to the resilience of the human body—and perhaps the care of his community, who may have helped him survive as long as he did.

Looking Toward the Past—and the Future

The discovery of TBH1 opens a window onto a time when the earliest human societies of Southeast Asia were forging their way in a post-Ice Age world. They hunted, gathered, built shelters, and formed communities—but they also quarreled, competed, and fought. Violence, it seems, is not just a product of modern states or armies but may have been woven into the human story from its very beginnings.

As more skeletons are unearthed in the caves and soils of Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and beyond, scientists may begin to piece together a fuller picture of how often conflict shaped prehistoric life in this region. For now, TBH1 stands alone—a solitary voice from the past, carrying a warning carved in bone.

The Legacy of a Fallen Hunter

Twelve thousand years later, the man from Thung Binh 1 cave still speaks to us. His fractured rib, his infected wound, and the tiny quartz shard lodged near his neck are all fragments of a story as old as humanity itself—the story of struggle, survival, and the thin line between life and death.

He is not just a skeleton in a cave; he is a reminder that the capacity for both care and conflict has always been part of who we are. And in remembering him, we catch a glimpse of ourselves in the deep mirror of time.

More information: Christopher M. Stimpson et al, TBH1: 12 000-year-old human skeleton and projectile point shed light on demographics and mortality in Terminal Pleistocene Southeast Asia, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2025.1819