In Egypt’s Western Desert — a place that once lay beneath warm ancient seas — a team of Egyptian paleontologists has uncovered a fossil that rewrites a chapter of reptile evolution. The desert now looks lifeless and silent, but in the wind-carved cliffs of Kharga Oasis, layers of red sandstone and green shale have preserved the bones of an animal that lived 80 million years ago. That animal is Wadisuchus kassabi, the earliest known member of a crocodile lineage that would outlive the dinosaurs and colonize the world’s coasts.

This discovery, now published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, is more than the naming of a new species. It shifts the timeline and geography of crocodile evolution, suggesting that a major branch of ancient marine crocodiles — the dyrosaurids — began in Africa millions of years earlier than previously thought.

The Dyrosaurids: Crocodiles That Chased Fish in Ancient Seas

Modern crocodiles lurk in rivers, swamps and lakes. Dyrosaurids were different. They hunted in saltwater ecosystems, their bodies shaped by the ocean. With long, narrow snouts filled with needle-sharp teeth, they were built for gripping slick prey like fish and marine turtles. They swam through coastlines in the last age of the dinosaurs — and when that age ended in fire and darkness, they endured.

The resilience of dyrosaurids after the mass extinction that erased most large reptiles has long puzzled scientists. Understanding how they evolved and spread could help explain how life rebounds when a world collapses. The discovery of Wadisuchus shines light on the beginning of that story.

Naming a Fossil That Carries Egypt in Its Bones

The name Wadisuchus kassabi combines place, culture, and gratitude. Wadi is Arabic for valley, echoing the New Valley region that sheltered the bones for tens of millions of years. Suchus honors the crocodile god Sobek, whose temples once lined the Nile. And kassabi memorializes the Egyptian paleontologist Ahmed Kassab, whose mentorship seeded a new generation of fossil hunters across the country.

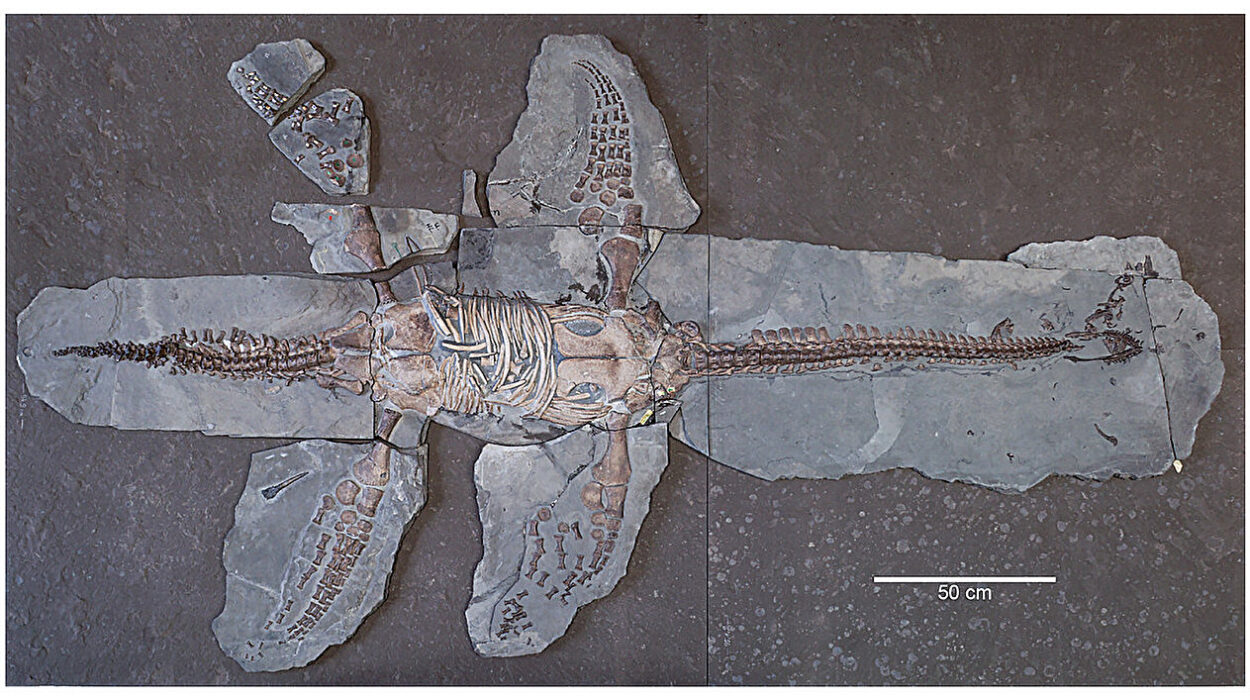

The fossils — two partial skulls and two snout tips — represent four individuals at different stages of growth. According to Professor Hesham Sallam of Mansoura University, who led the study, that diversity of ages is scientifically rare and precious. It provides direct insight into how these crocodile ancestors developed as they matured.

Inside the Skull: Anatomy of a Transitional Predator

Using high-resolution CT scans and 3D modeling, the researchers were able to digitally “peel back” layers of bone and fossil. What they found showed that Wadisuchus was not simply another marine crocodile — it was a transitional form, carrying early hallmarks of the dyrosaurid design.

Lead author Sara Saber of Assiut University describes an animal three and a half to four meters long, with a slender snout and tall cutting teeth. But its anatomy held clues of evolutionary change: four teeth at the tip of the snout instead of five; nostrils perched high for surface breathing; and a deep notch where the jaws locked together. These features document the gradual refinement of the dyrosaurid bite — the exact innovation that later made them successful ocean hunters.

Even more striking is what these skulls imply about time. The origin of this group now appears to predate previous estimates by millions of years. Rather than arising shortly before the mass extinction 66 million years ago, dyrosaurids may already have been diversifying in Africa as early as 87–83 million years ago.

Africa as the Cradle of a Global Lineage

Belal Salem, a member of the Sallam Lab and a researcher at Ohio University and Benha University, emphasizes the broader evolutionary consequence: the family tree of dyrosaurids appears to start on African soil. The anatomical and phylogenetic data place Wadisuchus at the base of the dyrosaurid branch — an ancestor from which later lineages radiated across ancient seas.

If this interpretation holds, Africa was not merely a refuge after extinction but the birthplace of a lineage of marine reptiles that later spread to multiple continents. The desert rock that now seems barren once served as a launch point for a global evolutionary drama.

Fossils as a National Treasure Still in the Ground

The scientists behind the discovery are Egyptian, trained in Egyptian institutions, studying fossils on Egyptian land. In their words, the significance of Wadisuchus lies partly in its scientific contribution and partly in what it proves about Egypt itself: the Western Desert is still full of secrets waiting to be revealed. The oases at Kharga and Baris, where this fossil rested for millions of years, are not empty wastelands but open-air archives of deep time.

Salem warns that these fossil-bearing landscapes are vulnerable. Urban growth and agricultural expansion threaten to erase sites before they are even documented. The team frames its mission not only as discovery but protection: to record and preserve the nation’s paleontological heritage for future generations.

A Window Into the Past and a Signal to the Future

Wadisuchus kassabi is more than an ancient skull in wind-cut stone. It is a messenger from a vanished world, showing how life responded to global catastrophe once before. It demonstrates that transformative lineages can begin quietly, on a shoreline now buried beneath sand, long before anyone names them.

It also testifies to the power of scientific work rooted in place. Egyptian researchers, using modern techniques on Egyptian earth, have shifted the narrative of reptile evolution on a global scale. Their discovery alters how the story is told in textbooks, museums, and classrooms — and it does so from within the country whose desert protected the evidence.

In the bones of a long-dead crocodile with a narrow snout and ocean-sharp teeth lies a reminder: the earth still holds answers to questions we have not yet learned to ask. And the deserts of Egypt, silent but not empty, may yet change what the world knows about life’s long history of adaptation, survival, and rebirth.

More information: An early dyrosaurid (Wadisuchus kassabi gen. et sp. nov.) from the Campanian of Egypt sheds light on the origin and biogeography of Dyrosauridae, Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society (2025). DOI: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaf134