In the heart of the Arabian Peninsula lies one of history’s most tantalizing enigmas—a city whispered about in ancient scriptures, praised in legend, and pursued by explorers for centuries. This city is Ubar, sometimes called Iram of the Pillars, a fabled settlement said to have thrived on the trade of frankincense and riches before it was swallowed by the desert sands. To speak of Ubar is to weave together myth and archaeology, poetry and geology, and the human yearning to find what has been lost.

For generations, Ubar has stood as the Arabian counterpart to Atlantis: a once-great city punished by divine wrath or undone by its own hubris. But unlike the purely mythological Atlantis, Ubar rests somewhere in the hazy borderland between legend and history. Its existence is hinted at in religious texts, described by medieval geographers, and pursued by modern scientists with satellites and excavation tools. To explore the story of Ubar is to embark on a journey across time, culture, and desert landscapes that still guard their secrets jealously.

The Land of Frankincense

To understand why Ubar holds such allure, one must first grasp the world in which it supposedly thrived. Southern Arabia, particularly the regions that are now Oman and Yemen, was the cradle of one of the ancient world’s most coveted commodities: frankincense. This aromatic resin, drawn from the Boswellia tree, was once worth more than gold. It was burned in temples across Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Rome; it perfumed palaces, healed wounds, and played a central role in rituals.

The frankincense trade routes crisscrossed Arabia, linking remote desert settlements to the bustling cities of the Mediterranean and India. Caravans of camels laden with resin passed through waystations, each thriving on the wealth that flowed from this trade. Ubar, as legend has it, was not merely one of these stations but a grand hub—a city of prosperity and splendor that stood as the crown jewel of Arabia’s desert kingdom.

Iram of the Pillars in the Qur’an

The earliest and most evocative reference to Ubar comes from the Qur’an, where it is described as “Iram of the Pillars.” The verses speak of a people known as ‘Ad, who built towering structures and lived in opulence. Their pride and corruption, however, brought divine punishment: a furious windstorm that buried their city beneath the sands. The tale of Iram echoes other narratives of civilizations brought low by arrogance—reminders that wealth and power can be fleeting in the face of nature’s wrath and divine will.

This mention in the Qur’an transformed Ubar from a trade city into a symbol. For believers, it was a warning wrapped in history. For explorers and scholars, it was a tantalizing clue: if the Qur’an spoke of Iram, then perhaps it was not just allegory, but a place that once existed. The challenge lay in finding it.

Echoes in Ancient Texts

Beyond the Qur’an, echoes of Ubar resound in other ancient writings. Classical geographers such as Pliny the Elder and Ptolemy wrote of southern Arabian cities enriched by the incense trade, places of immense wealth situated along caravan routes. Though they did not use the name Ubar, their descriptions conjured images of settlements that could very well match the grandeur ascribed to it.

Medieval Islamic geographers like al-Hamdani also described vanished cities and regions that thrived on frankincense, fueling speculation about whether these accounts pointed to the same lost settlement. In their writings, Ubar becomes less a single pinpoint on the map and more a symbol of a vanished world, one that flickered in and out of the human record.

The Allure of the Unknown

For centuries, Ubar was spoken of in hushed tones by travelers and Bedouins who roamed the vast Rub’ al Khali—the Empty Quarter, the largest sand desert on Earth. The desert is both breathtaking and unforgiving, a place where dunes rise like mountains and shifting sands erase the footprints of history. Rumors circulated of collapsed cities buried under dunes, of wells and fortresses swallowed whole. Explorers of the 19th and 20th centuries set out in search of this Arabian Atlantis, often guided more by hope than by evidence.

The romance of Ubar captivated Western imaginations as well. Writers compared it to El Dorado or the fabled city of gold. Adventurers dreamed of uncovering a metropolis of lost riches. Yet, despite repeated searches, Ubar remained elusive, mocking those who sought it, as if the desert itself guarded its memory.

The Breakthrough with Satellites

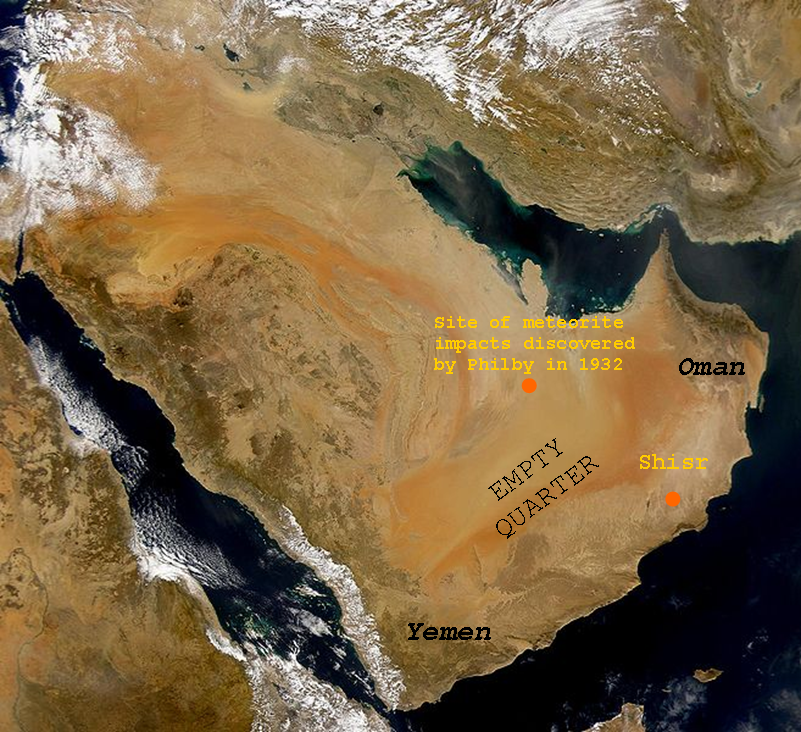

It was not until the late 20th century that technology offered new hope of finding Ubar. In the early 1990s, NASA and a team of archaeologists led by Nicholas Clapp, an amateur filmmaker with a passion for Arabian history, turned to satellites. Using radar imaging that could penetrate desert sands, they traced the ancient caravan routes etched faintly into the Earth. These routes, once invisible to the naked eye, formed a web converging on a single point in the desert of Oman.

The point lay near the modern settlement of Shisr. Excavations revealed collapsed structures, fortifications, and a massive underground limestone cavern into which parts of the city had sunk. The evidence suggested that Shisr had indeed been a major stop along the incense route. For some, this was the long-awaited discovery of Ubar.

Shisr: Ubar or Something Else?

The excavations at Shisr uncovered walls, pottery, and artifacts dating back to several millennia. There were signs of fortifications and evidence of water storage, essential for sustaining caravans in the desert. Most strikingly, the collapse of the limestone cavern beneath the site may have contributed to its sudden downfall, echoing legends of a city swallowed by the Earth.

Yet the question remains: was Shisr truly Ubar? Some scholars argue that Ubar was never a single city but rather a broader region or network of settlements tied to the incense trade. Others suggest that Ubar was a poetic name, a symbol for the wealth and culture of southern Arabia, not a precise urban location. In this view, Shisr may be one piece of the puzzle, but not the whole.

The debate highlights the tension between myth and archaeology. Legends compress centuries of history into a single story, while science uncovers fragments that complicate neat narratives. Ubar may never resolve into a single place on the map, but its spirit endures in both the discoveries at Shisr and the mysteries that remain.

The Punishment of Pride

One of the enduring themes of Ubar’s story is the fall of a people consumed by pride. In the Qur’anic account, the people of ‘Ad defied warnings, reveling in their power and monuments, until they were swept away by a storm. This motif recurs in human history: civilizations rise, flourish, and collapse, often undone by overconfidence, greed, or environmental change.

For archaeologists, the collapse of Shisr into a sinkhole offers a natural explanation for the legend. But the metaphor is as powerful as the geology. A city that grew fat on wealth from the incense trade, dominating desert routes, could not endure forever. When the trade declined, and when nature intervened, Ubar became a ruin swallowed by time.

The Desert’s Role as Keeper of Secrets

The Rub’ al Khali is more than a backdrop to the story of Ubar—it is its guardian. Stretching over 650,000 square kilometers, the Empty Quarter is a land of silence, where dunes shift like waves and landscapes can vanish overnight. In such a place, the disappearance of a city is not surprising. Sand both erases and preserves, burying evidence for centuries until it is uncovered.

The desert’s hostility has also kept explorers at bay. Until the advent of modern vehicles and technologies, venturing into the Empty Quarter was a perilous undertaking. Even today, the region is sparsely populated, its secrets still hidden beneath dunes that seem to move with a will of their own. It is no wonder that legends flourished in such a place, where the land itself seems alive and unpredictable.

Ubar in Modern Culture

The rediscovery of Shisr and the enduring mystery of Ubar have inspired modern imaginations as much as ancient ones. Books, documentaries, and films have dramatized the search, casting Ubar as an Arabian Atlantis. Adventure novels place it alongside other lost cities like Petra or Machu Picchu, symbols of humanity’s fascination with what has been hidden and forgotten.

Ubar has also become a symbol of Arabian heritage. For Oman, the discoveries at Shisr underscored the country’s role in the ancient incense trade and its connection to one of the world’s greatest stories of lost civilizations. Today, Shisr is a UNESCO World Heritage site, celebrated as part of the “Land of Frankincense,” linking legend to living culture.

Lessons from a Lost City

Whether Ubar was a grand city swallowed by sand, a network of settlements, or a poetic symbol, its story carries lessons that resonate today. It warns of the fragility of wealth and power, of the way human achievements can vanish before the forces of nature. It reminds us that the Earth itself is an actor in history, shaping civilizations as much as kings and merchants.

On another level, Ubar speaks to the human spirit of curiosity. For centuries, people searched for it not only out of greed or glory but from a deeper need to connect with the past, to prove that legends are not merely stories but windows into truths we have forgotten. In every generation, the search for Ubar rekindles this desire to uncover what lies hidden, to bridge the gap between memory and reality.

The Enduring Mystery

So, what is Ubar? A city of pillars buried beneath the sands? A collapsed fortress at Shisr? A symbol of Arabian prosperity and pride? Or perhaps all of these at once?

The beauty of Ubar’s story lies in its refusal to be pinned down. It exists on the shifting boundary between myth and history, between faith and science. Each discovery adds to its richness, but the mystery remains. The desert still holds countless secrets, and Ubar continues to shimmer on the horizon, half-real, half-imagined, a mirage that refuses to vanish.

Perhaps that is the true essence of Ubar. Not merely as a city lost, but as a story found—again and again—in the sands of Arabia, in the pages of scripture, and in the hearts of those who yearn for wonder.