In the great sweep of human history, the Stone Age stretches long and wide like a canvas etched with the earliest fingerprints of ingenuity. Our ancestors left behind blades, axes, and splinters of flint, buried beneath soil and time. For generations, these silent witnesses to prehistoric life have spoken to us only in fragments—pointing to a world where survival depended on more than strength. It demanded tools. It demanded thought.

Now, a team of researchers in Japan has given these ancient stones a voice again—not through guesswork or imagination, but by recreating the tools themselves, using them as our ancestors might have, and studying the marks they left behind.

What they found could reshape our understanding of how early humans shaped their world.

A Closer Look at the Edge of History

Led by Assistant Professor Akira Iwase of Tokyo Metropolitan University, the team set out to answer a deceptively simple question: What did these early stone tools actually do? Were they used to scrape hides, butcher meat, carve bone—or were they powerful enough to bring down trees?

In the world of archaeology, tools tell stories not just by where they’re found, but by how they’re worn. Edges chip, polish smooths surfaces, grooves deepen where friction was greatest. These are the fingerprints of purpose. But until now, the challenge has been distinguishing between overlapping signs of wear—between tools carried often but used rarely, and those that left their mark on the woods and wilds of a vanished world.

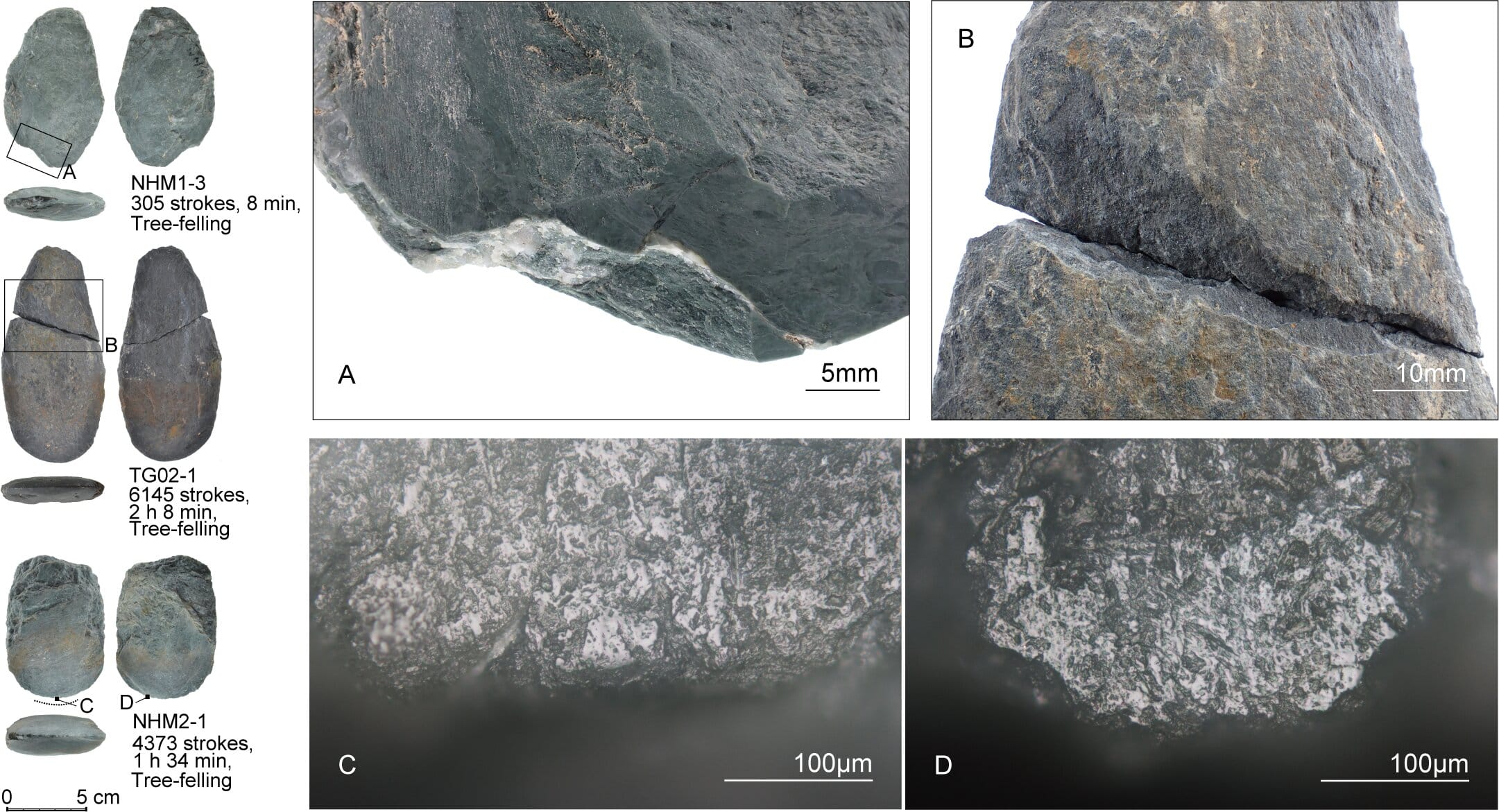

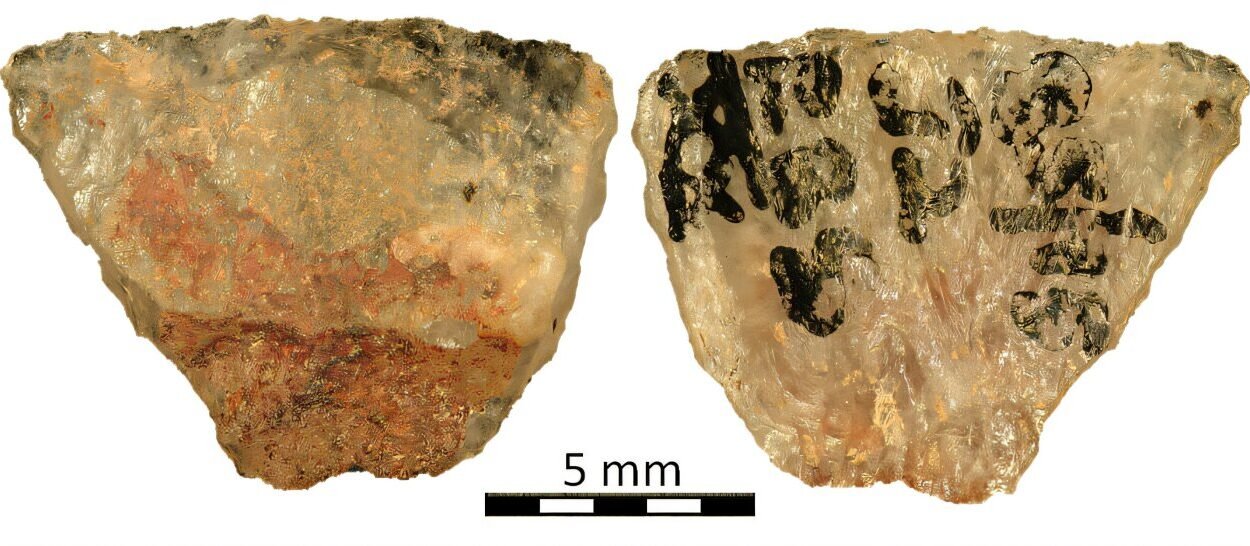

To find answers, the team turned to replication archaeology, a field where ancient craftsmanship meets modern science. They carefully recreated stone axes, adzes, and chisels using the same methods likely available to humans during the Early Upper Paleolithic period—around 38,000 to 30,000 years ago. Polished and knapped into shape, the tools were then hafted, or fitted with handles, using techniques borrowed from traditional methods observed in Irian Jaya, Indonesia.

No manuals. No machines. Just stone, wood, and the wisdom of experimentation.

Stone in Action: Testing the Tools of the Ice Age

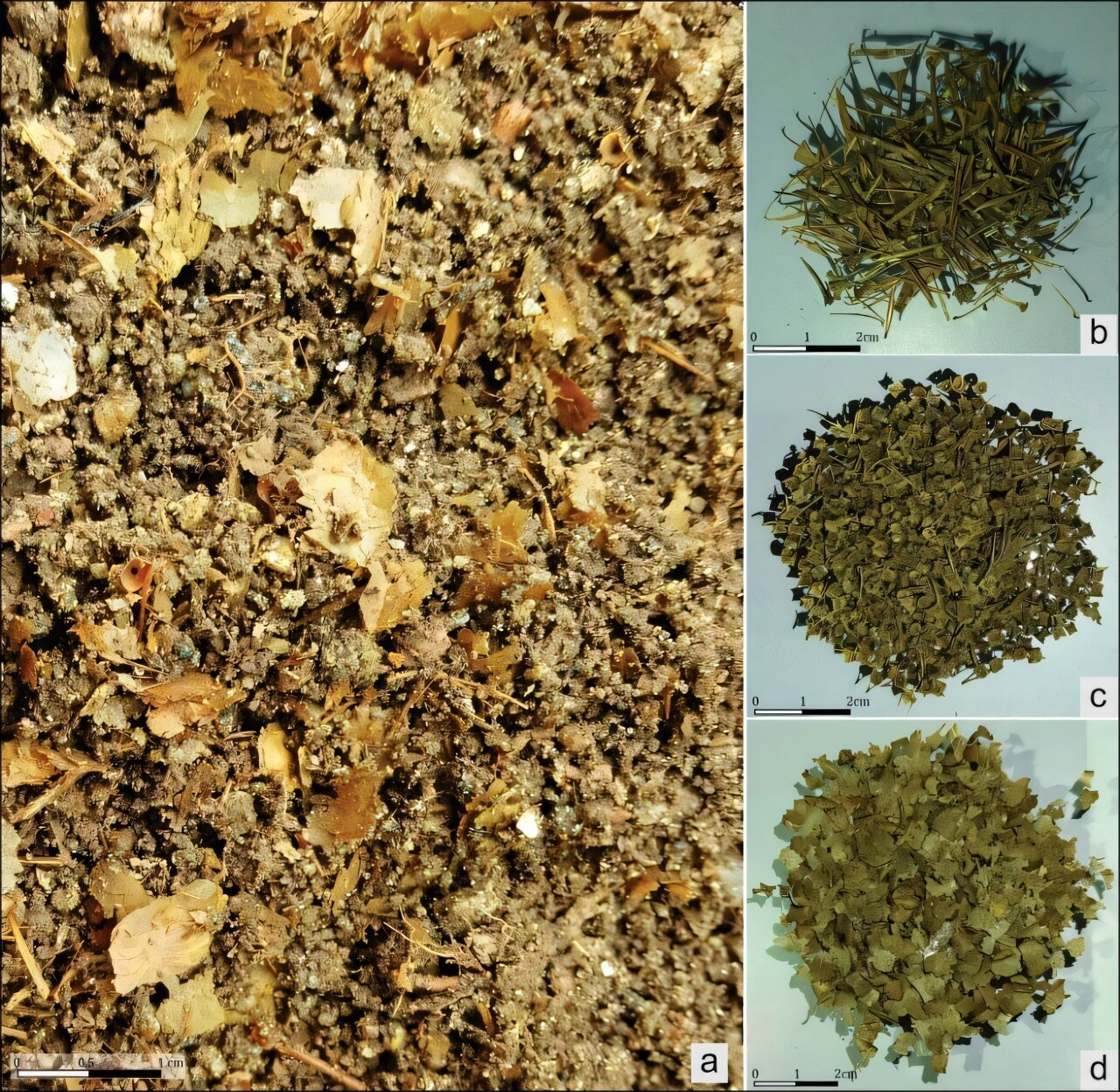

Once the replicas were complete, they weren’t placed on shelves or in glass cases. Instead, they were put to work. Over weeks and months, researchers used the tools for a wide range of activities, from felling trees and chopping wood to scraping animal hides and butchering meat. Some were even subjected to daily wear without purpose—carried around, dropped, trampled underfoot—to better understand how simple handling might mimic use.

Then came the real investigation.

Every edge, every fracture, every glimmering polish under the microscope was studied. On a macroscopic level, the tools used for cutting trees showed distinct fractures—large, visible scars from the repetitive and forceful impacts of chopping. But it was on the microscopic level that the story deepened. There, scientists found faint striations and polish patterns that revealed consistent wood-on-stone friction—a unique fingerprint of true woodworking, invisible to the naked eye but unmistakable under the lens.

What emerged was a kind of forensic language. Alone, neither the big fractures nor the fine polish could confirm exactly what a tool had been used for. But when examined together, they formed a reliable signature. It became possible to say: Yes, this edge felled trees.

Timber in the Ice: A Revolution Before Its Time

This might seem like an arcane detail, but it carries weight that stretches across continents and millennia. For decades, archaeologists believed that serious woodworking—like felling trees and shaping timber into structures—only became common during the Neolithic period, around 10,000 years ago. This was the age when humans began farming, settling in one place, and building homes. Tools from that era, like ground and polished stone axes, were thought to represent a leap in complexity—evidence of a society now equipped to build canoes, wells, and permanent homes.

But the tools found in Australia and Japan tell a different story.

Some of these ground stone tools date back to Marine Isotope Stage 3, between 60,000 and 30,000 years ago—a time deep in the Paleolithic era, when humans were thought to be primarily hunters and gatherers, living in small mobile groups. The idea that people of that age had the technology and intent to process timber—to carve, craft, and maybe even build—is revolutionary.

Iwase’s team has shown that we now have a way to identify woodworking at this earlier stage, not based on assumptions or generalized shapes, but on scientific signatures left behind by stone and time.

If archaeologists begin finding similar microscopic traces on tools from ancient sites, it would suggest that human beings were exploiting wood not just for spears and digging sticks, but for complex projects, centuries—if not tens of thousands of years—earlier than we thought.

How Trees Tell the Story of Humanity

The significance of woodworking in human history goes far beyond carpentry. Wood was a material that required planning, coordination, and patience. Cutting down a tree isn’t a casual act—it’s a decision. Turning it into a structure, a boat, or a bow requires knowledge passed down, skill practiced, and a vision of the future. It means thinking ahead, staying put, or perhaps navigating rivers to unknown lands.

When early humans began felling trees, they weren’t just shaping wood. They were shaping their destiny.

And now, thanks to the painstaking efforts of Iwase and his team, we have a roadmap to trace this hidden revolution. By matching wear patterns on ancient tools to the ones created in controlled, experimental settings, archaeologists can begin to see where—and when—this timber-based technology began to spread.

This could explain how humans adapted to vastly different environments. In tropical forests or dense woodlands, stone tools capable of working timber might have allowed for better shelters, rafts, or even strategic clearing of land. In places like Japan and Australia—regions with rich deposits of these tools—we might find a story of ancient adaptability, powered not just by fire and flint, but by wooden ingenuity.

The Future Carved in Stone

In the end, these aren’t just dusty stones from another age. They’re pieces of a larger puzzle—one that includes language, culture, innovation, and survival.

Understanding how and when humans learned to work with wood adds an entirely new chapter to the story of our species. It challenges the idea that only settled farmers developed complex technology. It reminds us that even nomadic hunter-gatherers—roaming the edge of glaciers or tropical forests—were capable of extraordinary engineering, long before the invention of the wheel or the written word.

And it highlights the quiet power of replication science—of trying things out, of letting action and wear and experiment speak where memory has failed.

From fractured stone to the fell of ancient trees, the forest has always been a mirror for human transformation. We shaped it, and in turn, it shaped us. Perhaps our first homes, our first tools, even our earliest myths began not in stone, but in timber—carved and cut by hands that knew how to dream in wood.

Reference: Akira Iwase et al, Experiments with replicas of Early Upper Paleolithic edge-ground stone axes and adzes provide criteria for identifying tool functions, Journal of Archaeological Science (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2023.105891