For centuries, Vindolanda has whispered its secrets slowly. Buried beneath damp soil near Hadrian’s Wall, the Roman fort has yielded wooden letters, worn leather shoes, and traces of daily life from a distant frontier of an empire. But now, something far more intimate has emerged from the earth. Something that once lived inside the bodies of the soldiers themselves.

A new scientific analysis of sewer drains at Vindolanda has revealed that the men stationed there were not only guarding a cold, rain-soaked border. They were also carrying unseen passengers within them. Intestinal parasites. Three kinds, to be precise: roundworm, whipworm, and Giardia duodenalis.

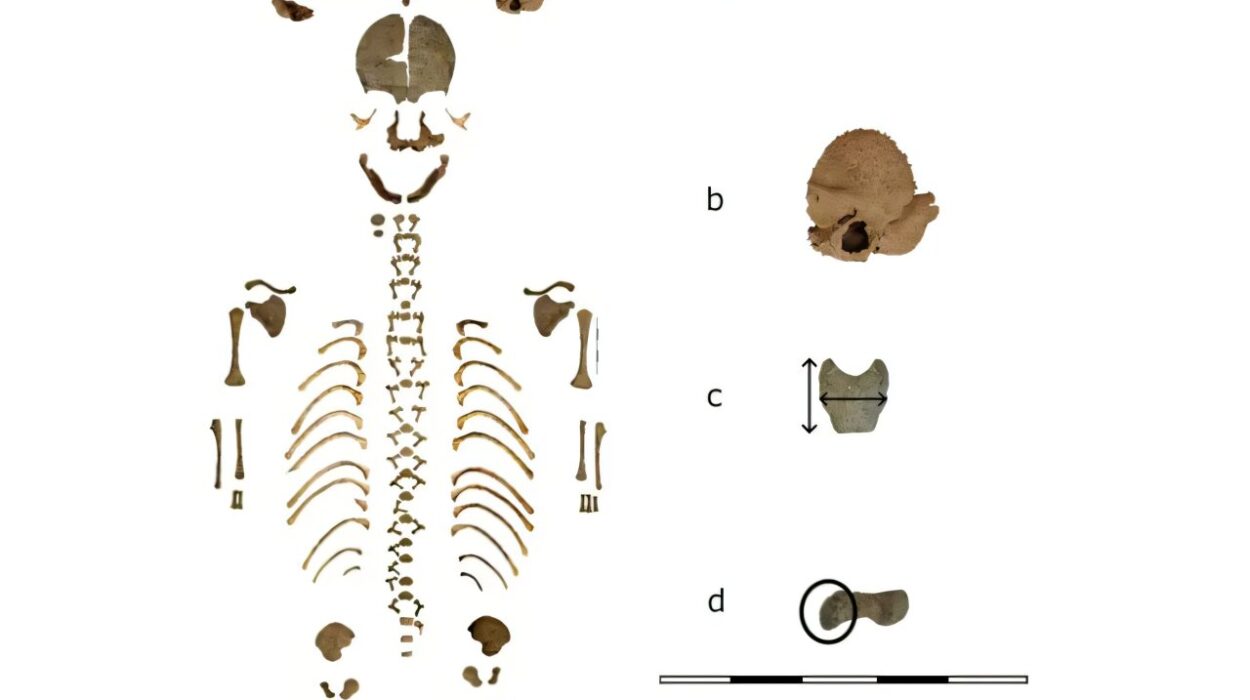

These discoveries were not found in grand buildings or ornate artifacts, but in the sediment of a latrine drain. In what the soldiers left behind, researchers found a vivid biological record of hardship, illness, and the limits of ancient sanitation.

Following the Flow of an Ancient Latrine

The story begins in the remains of a bath complex from the 3rd century CE. From its communal latrine, a sewer drain once carried waste downhill for about nine meters, eventually emptying into a stream north of the fort. Over time, that drain filled with sediment, trapping small remnants of the lives that passed through it.

Researchers from the universities of Cambridge and Oxford carefully collected fifty sediment samples along the length of this drain. Mixed into the ancient waste were Roman beads, fragments of pottery, and animal bones. But the most revealing finds were invisible to the naked eye.

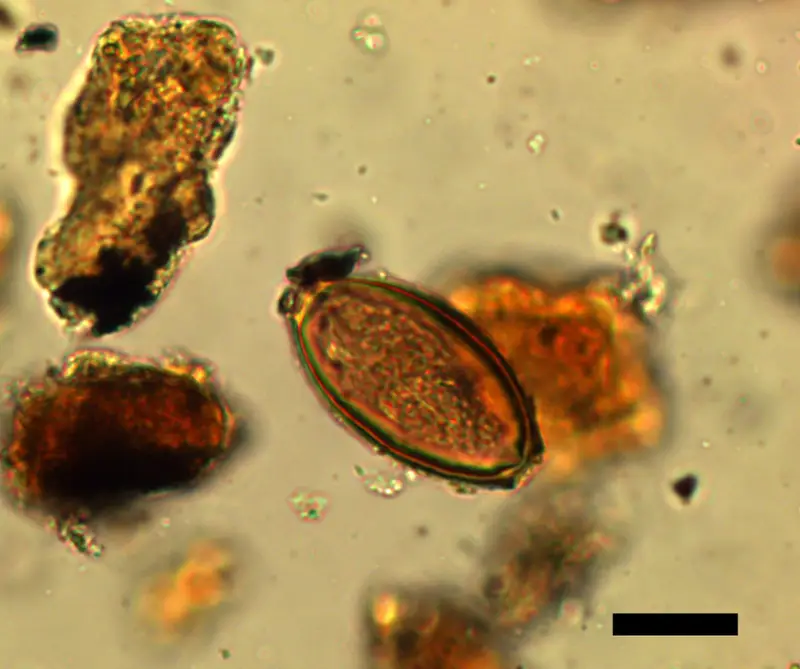

In laboratories at Cambridge and Oxford, scientists placed the samples under microscopes, searching for the ancient remains of helminth eggs. These eggs, produced by parasitic worms, can survive for thousands of years in the right conditions.

The results were striking. Around 28% of the samples contained eggs from either roundworm or whipworm. One sample, however, told a deeper story.

A Microscopic First for Roman Britain

That particular sample held remnants of both roundworm and whipworm. To investigate further, researchers used a technique called ELISA, where antibodies bind to proteins produced by single-celled organisms. Through this method, they detected traces of Giardia duodenalis.

This marked the first evidence of Giardia duodenalis ever found in Roman Britain.

Unlike the worms, Giardia is microscopic. It is a protozoan parasite known to cause outbreaks of diarrhea, particularly when sanitation fails and water becomes contaminated. Its presence suggests not just individual illness, but the possibility of group infections spreading quickly through the fort.

The parasites identified are all spread through ineffective sanitation, when food, drink, or hands become contaminated with human feces. Roundworms, which can grow to 20–30 cm long, and whipworms, about 5 cm long, would have lived quietly inside infected soldiers. Giardia, though unseen, could have caused sudden and severe sickness.

Echoes From an Even Earlier Fort

The researchers did not stop with the 3rd-century drain. They also examined a sample connected to an earlier fort built around 85 CE and abandoned just a few years later. This sample came from a defensive ditch, not a latrine, yet it contained both roundworm and whipworm eggs.

This finding suggests that intestinal parasites were present at Vindolanda from its earliest days. Across different phases of construction and occupation, the soldiers faced the same biological threats, passed from person to person in ways they could not fully control or understand.

Life on the Edge of an Empire

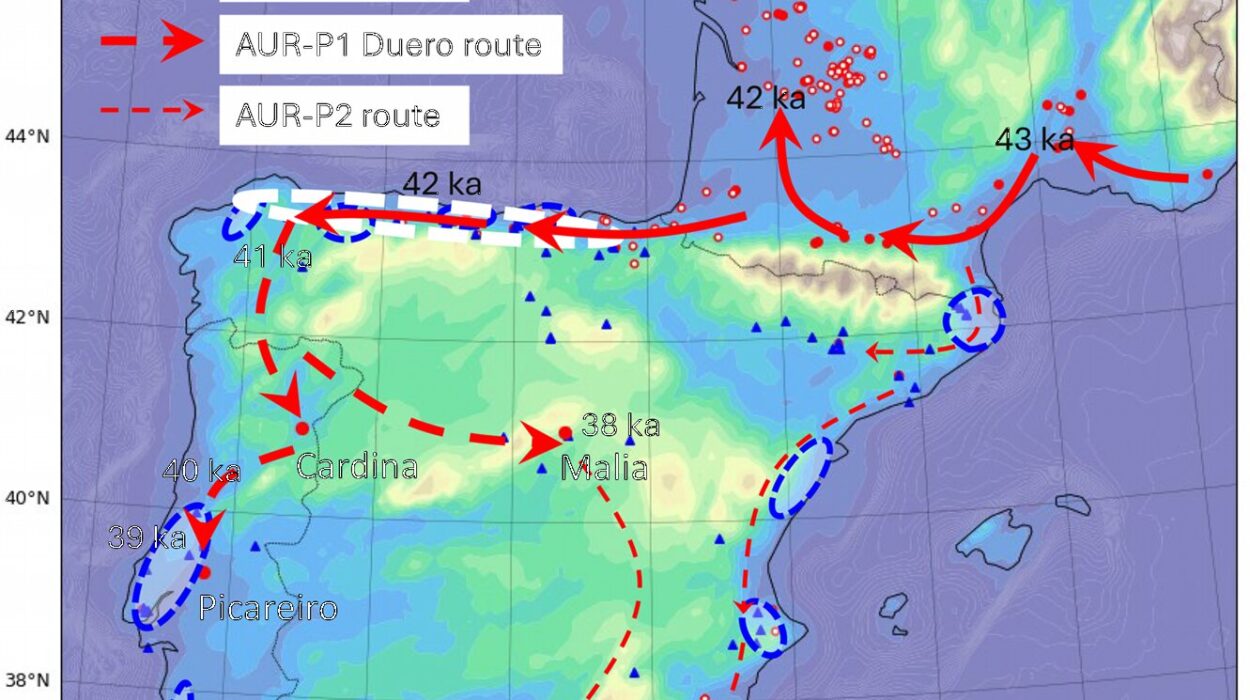

Vindolanda stood near Hadrian’s Wall, a massive defensive barrier built by the Romans in the early 2nd century AD to protect their province of Britannia from northern tribes. Stretching east to west from the North Sea to the Irish Sea, the wall was lined with forts and towers and defended by infantry, archers, and cavalry drawn from across the Roman Empire.

Vindolanda itself lies between Carlisle and Corbridge in what is now Northumberland, Britain. The fort is famous for its exceptional preservation, especially organic materials. More than 1,000 thin wooden tablets written in ink reveal personal letters and administrative details. Over 5,000 Roman leather shoes tell stories of feet worn by marches, mud, and cold.

Now, the parasites add another layer. They speak of bodies under strain.

Illness Without Cure

“The three types of parasites we found could have led to malnutrition and cause diarrhea in some of the Roman soldiers,” said Dr. Marissa Ledger, who led the Cambridge component of the study as part of her Ph.D. at the University of Cambridge’s Department of Archaeology.

“While the Romans were aware of intestinal worms, there was little their doctors could do to clear infection by these parasites or help those experiencing diarrhea, meaning symptoms could persist and worsen. These chronic infections likely weakened soldiers, reducing fitness for duty. Helminths alone can cause nausea, cramping and diarrhea.”

The picture that emerges is one of lingering illness. Soldiers who may have felt constantly fatigued. Men whose strength slowly ebbed, not from battle wounds, but from infections they could not escape.

When Water Becomes a Threat

Dr. Piers Mitchell, the study’s senior author and an Affiliated Scholar at Cambridge’s McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, highlighted the danger posed by Giardia in particular.

“Some soldiers could have become severely ill from dehydration during summer outbreaks of Giardia, which are often linked to contaminated water and can infect dozens of people at a time. Untreated giardiasis can drag on for weeks, causing dramatic fatigue and weight loss.”

In a crowded military fort, where water sources were shared and sanitation was imperfect, such outbreaks could have spread rapidly.

Mitchell added another troubling possibility. “The presence of the fecal-oral parasites we found suggests conditions were ripe for other intestinal pathogens such as Salmonella and Shigella, which could have triggered additional disease outbreaks.”

The parasites may be only part of a much larger picture of sickness that once moved silently through the fort.

Sanitation That Was Not Enough

Vindolanda had communal latrines and a sewer system, features often associated with Roman engineering sophistication. Yet these measures did not stop the spread of parasites.

“Despite the fact that Vindolanda had communal latrines and a sewer system, this still did not protect the soldiers from infecting each other with these parasites,” said Dr. Patrik Flammer, who analyzed samples at the University of Oxford.

The findings align with evidence from other Roman military sites, where fecal-oral parasites dominate. Urban centers such as London and York show a broader range of parasites, including fish and meat tapeworms, reflecting differences in diet and lifestyle. At frontier forts like Vindolanda, the biological signature is simpler, but no less severe.

Reading Disease in Ancient Soil

For the scientists involved, the study goes beyond Vindolanda itself.

“The study of ancient parasites helps us to know the pathogens that infected our ancestors, how they varied with lifestyle, and how they changed over time,” said Prof Adrian Smith, who led the Oxford lab where part of the analysis was performed.

By examining what survives in soil, researchers reconstruct patterns of health, hygiene, and daily living that written records rarely capture.

Dr. Andrew Birley, CEO of the Vindolanda Charitable Trust, emphasized how these findings reshape our understanding of life on Rome’s northwestern frontier.

“Excavations at Vindolanda continue to find new evidence that helps us to understand the incredible hardships faced by those posted to this northwestern frontier of the Roman Empire nearly 2,000 years ago, challenging our preconceptions about what life was really like in a Roman frontier fort and town.”

A Poet’s Line, Now With New Meaning

The Roman poet’s misery has long been imagined. W. H. Auden once wrote of a soldier guarding a rain-soaked wall, burdened by “lice in my tunic and a cold in my nose.” With the evidence now emerging from Vindolanda’s drains, it seems clear that something far worse was happening inside those soldiers’ bodies.

Serious stomach trouble was likely a constant companion.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research matters because it brings us closer to the lived reality of the past. It reminds us that history is not only shaped by emperors, battles, and monuments, but by fragile human bodies struggling against illness. By identifying parasites in ancient waste, scientists reveal how disease moved through communities, how sanitation failed even in advanced systems, and how health shaped the effectiveness of entire military units.

Vindolanda’s soldiers were not just guarding an empire’s edge. They were enduring chronic infections, fatigue, and weakness while far from home. Understanding these hidden hardships deepens our picture of Roman life and challenges romantic ideas of imperial strength.

In the end, the smallest traces in the soil tell the most human stories.

More information: Marissa L. Ledger et al, Parasite infections at the Roman Fort of Vindolanda by Hadrian’s Wall, UK, Parasitology (2025). DOI: 10.1017/s0031182025101327