For centuries, archaeologists and historians have carried a powerful stereotype into their interpretations of the distant past: the idea of “Man the Hunter.” Stone tools, sharp and purposeful, were thought to belong almost exclusively to men—symbols of masculine labor, strength, and survival. Women, according to this long-held view, tended to domestic life: preparing food, weaving, and raising children, far removed from the realm of weapons and tools.

But a new study from one of Europe’s largest Stone Age burial sites has turned this narrative upside down. At the Zvejnieki cemetery in northern Latvia, where more than 330 graves have been uncovered, researchers have discovered that stone tools were not the exclusive possession of men. They were found just as often—if not more often—buried with women and children. This discovery forces us to reimagine the roles of early societies and to see Stone Age life and death in a new, more nuanced light.

A Cemetery Full of Stories

The Zvejnieki site is extraordinary. Used for over 5,000 years, it preserves the lives of generations of communities who lived, hunted, loved, and died along the shores of prehistoric lakes. Thousands of ornaments made from animal teeth have been unearthed here, suggesting a culture rich with symbolism and ritual. Yet, until recently, the stone tools buried with the dead were largely ignored, dismissed as “ordinary” utilitarian items.

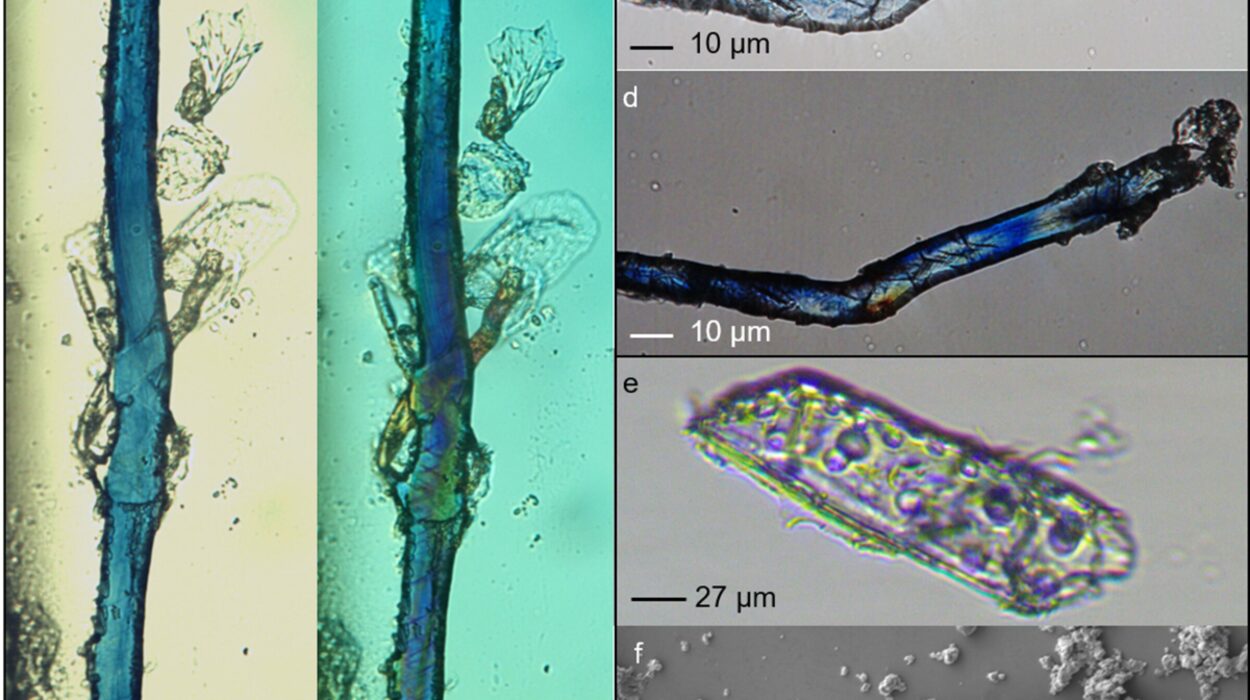

It took the Stone Dead Project, led by Dr. Aimée Little of the University of York, to look more closely. With the help of colleagues across Europe and the Latvian National Museum of History, the team brought high-powered microscopes to Riga to examine the artifacts in minute detail. What they discovered was that these tools were anything but ordinary.

The Hidden Meaning of Stone Tools

The study revealed two striking patterns. First, women and children were frequently buried with stone tools—sometimes even more often than men. This finding disrupts the stereotype of male dominance in tool use and suggests that tools may have held symbolic or practical significance for all members of society.

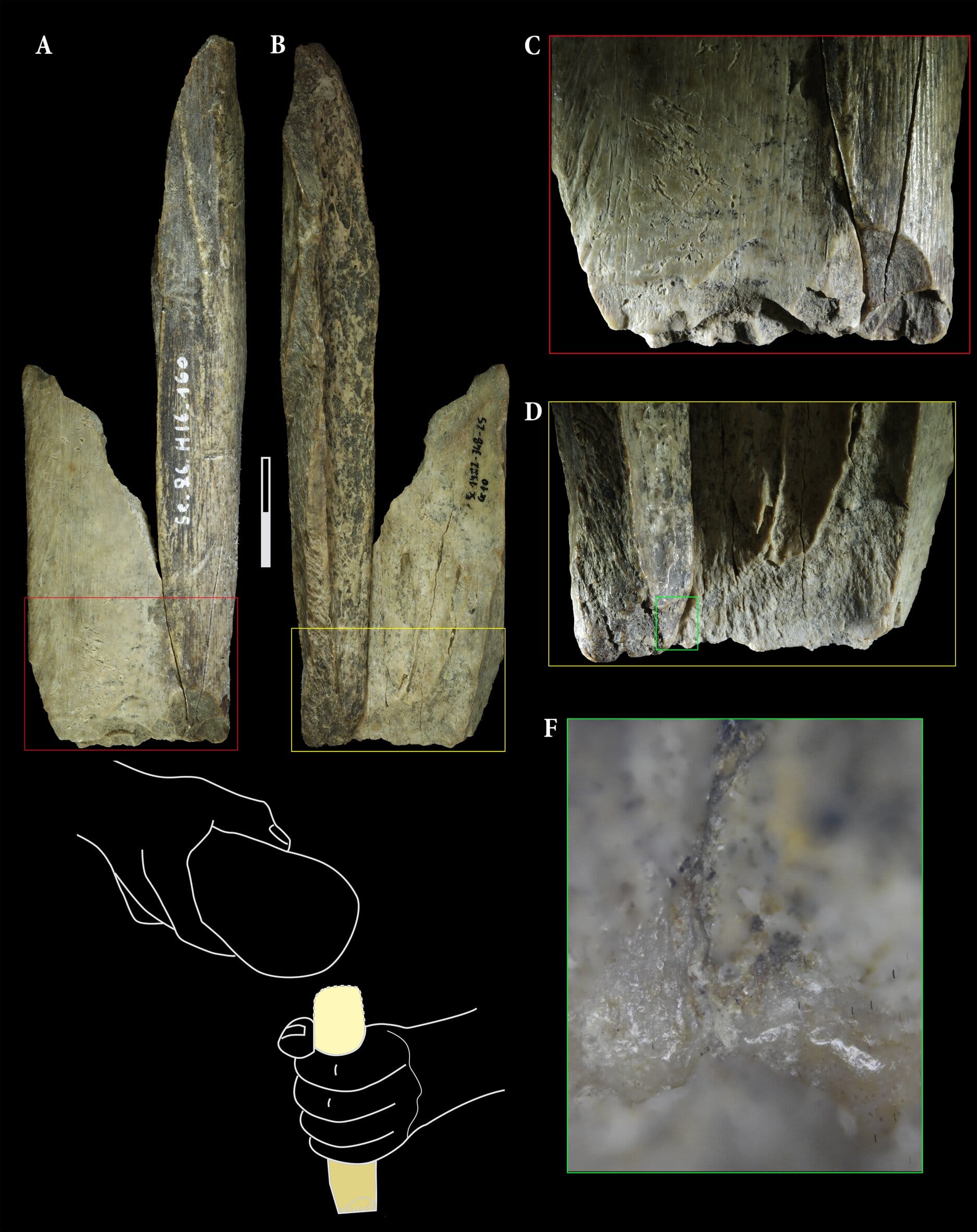

Second, the tools themselves carried a layered meaning. Some showed clear evidence of use, such as scraping hides or working animal materials. Others, however, had never been used. In fact, some appeared to have been purposefully crafted only to be broken before burial. This act of breaking suggests ritual, a symbolic gesture marking the transition between life and death. Rather than being “just tools,” these objects were tokens of identity, memory, and mourning.

Women, Children, and the Ritual of Death

Perhaps the most moving revelation from this study is the recognition of women and children as central figures in these burial practices. Children and older adults were the most likely to receive stone tools, hinting at their symbolic role within the community’s understanding of death and remembrance.

For women, the presence of tools in their graves challenges the rigid categories imposed by modern scholars on ancient life. The idea that they were confined solely to domestic spheres now seems narrow and incomplete. Instead, the evidence suggests that women were not only users of tools but participants in the broader symbolic world of Stone Age ritual.

Dr. Little herself highlights how these findings overturn old assumptions: “Our discoveries challenge the stereotype of ‘Man the Hunter.’ These artifacts show us that tools in the Stone Age were not gendered possessions, but shared symbols of human life, death, and community.”

Shared Rituals Across a Wider World

The deliberate breaking of tools before burial has been observed at other sites across the eastern Baltic, suggesting a widespread cultural tradition. By shattering a newly made tool and placing it with the deceased, communities may have been expressing ideas about transition, continuity, or release. It was a ritual act that bound the living and the dead, a way of acknowledging loss while reinforcing shared beliefs.

This practice reminds us that even in prehistory, people sought to make sense of death through symbols. Every chipped flint, every shattered blade carried more than physical utility—it carried meaning, memory, and hope.

Rethinking the Past

The Zvejnieki study, published in PLOS One, is more than an archaeological finding—it is a reminder of how easily we can project modern biases onto ancient societies. For too long, researchers assumed that tools equaled men, while ornaments equaled women. But the evidence tells a richer story: that tools were part of a collective human experience, deeply entwined with rituals of death and remembrance.

Dr. Anđa Petrović of the University of Belgrade notes that “we cannot make these gendered assumptions.” The graves of women and children show us that tools were far more than hunting instruments; they were emotional, cultural, and spiritual objects.

The Humanity Behind the Stones

At its core, this discovery is not just about tools or bones. It is about people. The Zvejnieki cemetery reveals a community that cared deeply about honoring its dead. The broken tools, the animal tooth pendants, the careful placement of objects in graves—all speak of love, memory, and belonging.

Even in the Stone Age, people asked the same questions we do today: How do we honor the lives of those we lose? How do we carry their memory forward? The answers they gave—through rituals of stone and symbol—remind us that we are part of a much longer human story.

Looking Forward Through the Past

As Dr. Little reflects, “The study highlights how much more there is to learn about the lives—and deaths—of Europe’s earliest communities, and why even the seemingly simplest objects can unlock insights about our shared human past.”

The tools of Zvejnieki are no longer silent. They tell us that the past was more complex than stereotypes allow. They show us a world where women, men, children, and elders all played roles in shaping community and ritual. And they remind us that in the end, the simplest stones can reveal the deepest truths about what it means to be human.

More information: Anđa Petrović et al, Multiproxy study reveals equality in the deposition of flaked lithic grave goods from the Baltic Stone Age cemetery Zvejnieki (Latvia), PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0330623