At the northwestern tip of Africa, where the rugged cliffs of Morocco lean toward the blue shimmer of the Strait of Gibraltar, lies a wind-swept landscape that has remained curiously silent in the grand narrative of Mediterranean prehistory. The Tangier Peninsula, caught between continents and epochs, has long been overlooked by archaeologists—its historical voice muffled by time, terrain, and a lack of sustained exploration.

Now, that silence is beginning to break.

A collaborative team of archaeologists—Hamza Benattia of Morocco’s National Institute of Archaeology and Heritage, Jorge Onrubia-Pintado of the University of Castilla-La Mancha, and Youssef Bokbot of the University of Barcelona—has uncovered a series of sites that are rewriting what we thought we knew about ancient North Africa. Their discovery of three prehistoric cemeteries, rock art shelters, and towering standing stones on the Tangier Peninsula is more than just a regional footnote—it’s a leap into the shadowy frontier of Mediterranean human history.

Digging into Forgotten Time: The Quest for 3000–500 BCE

The team set out with a clear purpose: to find evidence of early human presence on the peninsula, spanning the long window from 3000 BCE to 500 BCE. This period encompasses enormous cultural shifts across North Africa—the rise and fall of megalithic builders, the emergence of pastoral societies, and the early contact between African and European shores. Yet the Tangier Peninsula, a geographical keystone of these transformations, had remained archaeologically underexplored.

Their fieldwork, published in the African Archaeological Review, was designed to bridge that gap. Moving carefully across the windswept terrain, the archaeologists identified promising zones where natural rock formations, sediment patterns, and ancient land use suggested buried stories. What they found was far richer—and more complex—than they expected.

The Ancient Cemeteries: Stones, Spirits, and Social Memory

Among the team’s most dramatic discoveries were three separate cemeteries, including one that held a stone-lined cist burial dating back nearly 4,000 years—circa 2000 BCE, during the Middle Bronze Age. This period, associated with expanding trade networks and early metal use in the Mediterranean, has rarely been tied to concrete archaeological contexts in this part of Morocco. Until now.

The cist burial, carved painstakingly into rock and sealed with a heavy stone slab, speaks volumes about the people who once lived here. Constructing such a grave with primitive tools would have required immense communal effort and a sophisticated understanding of stonework and funerary practice. In life, this person may have been a leader, elder, or spiritual figure. In death, they were entombed with reverence and permanence.

Using radiocarbon dating, the team confirmed the age of the burial—a first for any cist burial in northwest Africa. This is a pivotal moment in archaeological science for the region. Radiocarbon dating offers not just a timestamp, but a key to synchronizing North African developments with those of early European and Near Eastern civilizations. The Tangier Peninsula, it turns out, was not on the periphery of history—but at its threshold.

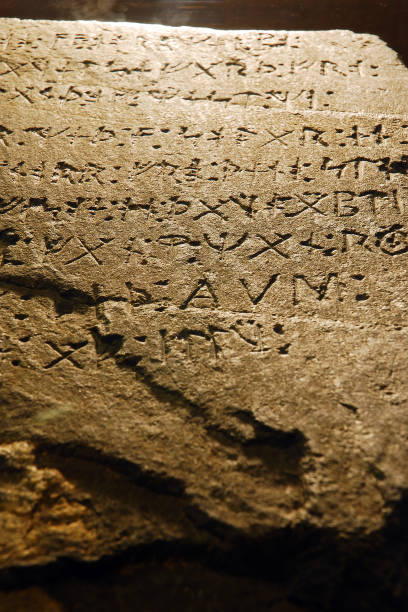

Marks on Stone: The Painted Rock Shelters

Yet it wasn’t only the graves that told stories.

Scattered nearby were natural rock shelters, many painted with geometric and symbolic forms. Some echoed the motifs found in the Sahara Desert’s ancient art, linking the coastal communities of the Tangier Peninsula to the great caravan routes and cultural migrations of inner Africa.

The presence of such rock art raises tantalizing questions. Were these shelters spiritual sites, perhaps shrines for the departed whose remains lay buried nearby? Were they meeting places or early classrooms—spaces where memory and myth were passed down in color and form?

What is clear is that symbolic communication was thriving in this region far earlier than previously thought. These are not just decorations—they are traces of cognitive sophistication, of social organization, and of belief systems we are only beginning to understand.

The Standing Stones: Guardians of the Past

The team also documented several standing stones, including one that towered an impressive 2.5 meters above the earth. Positioned both within cemeteries and alongside rock art shelters, these monoliths suggest intentionality in both placement and meaning.

Across the ancient world, standing stones served as territorial markers, astronomical tools, and sacred monuments. Their presence on the Tangier Peninsula hints at a people engaged in landscape engineering—not for defense or agriculture, but for cultural memory.

To stand among these stones is to glimpse a lost worldview: one where ancestors, spirits, and celestial rhythms shaped every facet of daily life. In erecting them, these ancient builders may have sought to bind heaven and earth, to fix their presence in a world where so much was impermanent.

A Crossroads of Civilizations and the Mystery of the Strait

The proximity of these sites to the Strait of Gibraltar adds an extra layer of intrigue. This narrow waterway—just 13 kilometers wide at its slimmest point—has always been a bridge between Africa and Europe. By 2000 BCE, seafaring was already advanced enough for short-distance voyages. Could the people of Tangier have been part of early trans-Mediterranean contact?

The presence of shared artistic styles between North Africa and southern Iberia suggests that ideas—and perhaps people—were moving back and forth across the water much earlier than classical historians imagined. These burial practices, rock art styles, and stone monuments may represent a cultural fusion unique to this maritime frontier.

The Tangier Peninsula, once seen as marginal, now emerges as a possible cultural melting pot, absorbing influences from the desert, the mountains, and across the sea.

Why It Matters: The Prehistoric Puzzle of North Africa

For centuries, North Africa’s deep prehistory has been overshadowed by the grand narratives of Egypt, Carthage, and Rome. But the lands west of the Nile and north of the Sahara were never silent. They held pastoralists, builders, artists, and navigators whose legacies still slumber beneath rocky soil and scrubby hills.

This latest discovery does more than add new sites to a map. It demands that we rethink how ancient people lived, traveled, and interacted across what we now consider cultural boundaries. It calls into question our assumptions about isolation and influence, about how and where civilization bloomed.

And it opens a new chapter for a peninsula that, until recently, had been left out of the story altogether.

The Road Ahead: Conservation, Collaboration, and Curiosity

The Tangier Peninsula is not just a site of archaeological interest—it is a fragile record of human ingenuity. As urban development, tourism, and climate change encroach on these landscapes, preserving these sites becomes urgent.

Benattia, Onrubia-Pintado, and Bokbot stress the importance of international collaboration, not just in fieldwork, but in heritage management. Their research is a model for cross-border archaeology, where Spanish and Moroccan scientists work together to illuminate a shared past.

There is much left to uncover. Who were the people buried in those stone-lined graves? What stories lie behind the painted shapes on cave walls? And how many more stones—buried, broken, or still standing—wait to be found?

Each answer brings a dozen new questions. And in the space between those questions, history breathes.

Conclusion: Stones That Speak

In the end, what the archaeologists discovered on the Tangier Peninsula is not just a few ancient graves or weathered drawings—it is a conversation across time. It is a reminder that even the wind-blown edges of the map are full of meaning, and that history often waits in silence until someone listens closely enough to hear it.

As we walk among the cist graves and painted rocks, as we trace the outlines of hands long vanished, we are not just visitors to a dig site. We are participants in a shared human journey—one that began long before writing, and which continues in every question we dare to ask about the past.

Reference: Hamza Benattia et al, Cemeteries, Rock Art and Other Ritual Monuments of the Tangier Peninsula, Northwestern Africa, in Wider Trans-Regional Perspective (c. 3000–500 BC), African Archaeological Review (2025). DOI: 10.1007/s10437-025-09621-z