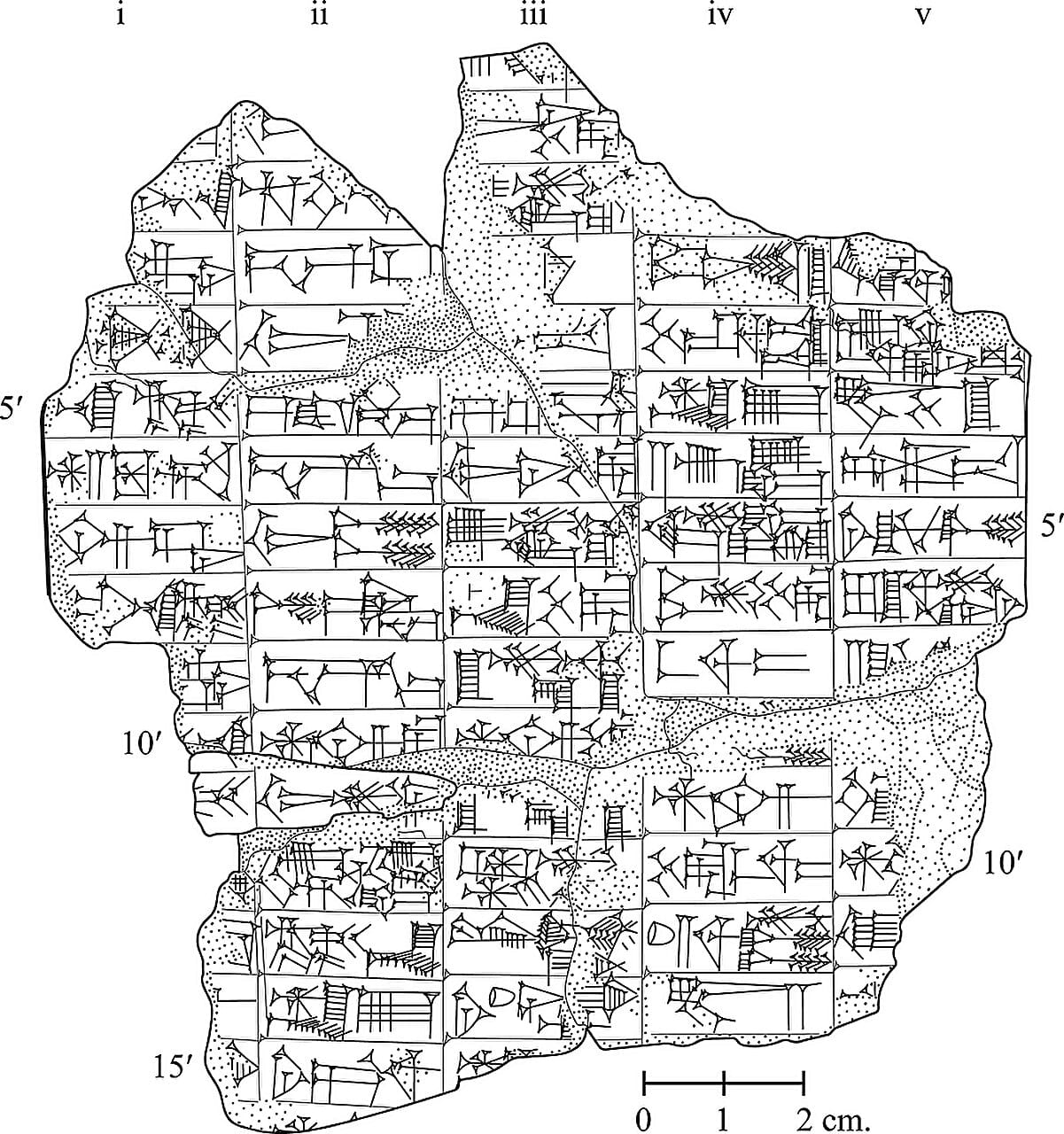

It was buried for thousands of years beneath the crumbling dust of ancient Nippur, in what is now southern Iraq. A single clay tablet, scarred by time and cracked like parched earth, lay hidden beneath millennia of silence. When it was finally brought to light in the 19th century, the world had no inkling of the fragile myth it carried—an echo from a vanished civilization, a voice from a pantheon that once ruled the imagination of Sumer.

For decades, the artifact sat largely unstudied. Even when it made its enigmatic appearance on the dust jacket of a 1956 book by famed Assyriologist Samuel Noah Kramer, its museum number—Ni 12501—was omitted, leaving it adrift in scholarship. It was only five years later that Kramer quietly revealed its identity. But by then, it had slipped back into obscurity.

Now, more than a century after its excavation, the tablet has found its voice again.

In a recent study published in the journal Iraq, Dr. Jana Matuszak has brought Ni 12501 back into the scholarly spotlight. With careful analysis and emotional clarity, she reveals not just a story of gods and monsters, but of rain and ruin, faith and famine, and the daring of a fox who journeys into the land of the dead.

A Kingdom of City-States and Shared Gods

To understand the weight of the myth preserved on Ni 12501, we must return to the world in which it was born—Sumer, around 2400 BCE. This was no unified empire but a delicate mosaic of independent city-states, each with its own temple, territory, and divine protector. Yet despite their political autonomy, these cities were bound together by language, writing, and shared religious beliefs. Like scattered stars orbiting a shared constellation, they revered a common pantheon, even if each city gave pride of place to its own patron deity.

In Nippur, the spiritual heart of Sumer, that deity was Enlil—the king of the gods. Though temples in Nippur housed other divine beings as well, it was Enlil who stood supreme. He commanded the divine assembly, shaped destinies, and governed the order of the cosmos. It is fitting, then, that the Ni 12501 tablet, which tells of Enlil’s decision to send a messenger into the underworld, was unearthed in Nippur itself.

“Each city-state had one patron deity,” Dr. Matuszak explains, “but cities had various temples dedicated to other deities as well. There’s evidence for local panthea, but the big gods were venerated throughout Sumer.” Thus, while the story on Ni 12501 might have been steeped in the local religious traditions of Nippur, it echoed across a broader cultural canvas.

Ishkur, the Storm, and the Vanishing of Rain

The central drama of Ni 12501 unfolds with the disappearance of Ishkur—the storm god, the bringer of rain, and the son of mighty Enlil. In a land where the rains rarely came on their own, this was no small deity. But his importance was paradoxical. Unlike the storm gods of the Semitic north, who ruled rainfed lands and fertile hills, Ishkur reigned over a region dependent on human ingenuity for survival. In southern Mesopotamia, rain alone could not sustain agriculture. Instead, the Sumerians channeled life from the twin rivers—the Tigris and Euphrates—through a web of canals and irrigation channels. The rains were symbolic, occasional, and mythically potent, but not agriculturally central.

Still, Ishkur mattered—because he represented more than just weather. He symbolized divine blessing, vitality, fertility. And in the tablet, he vanishes.

The tablet opens in a time of abundance. Glittering waters fill the rivers and canals, teeming with fish. Multicolored cows—cattle of divine stock—roam freely, belonging to Ishkur himself. But then, something shifts. Ishkur and his animals are seized and dragged into the kur, the netherworld. Darkness falls, not just on the land but on the womb of the earth itself. Children are born and then taken—perhaps a metaphor for death, or a poetic expression of famine and loss. The narrative teeters between myth and metaphor, between the divine and the mortal.

With Ishkur imprisoned, the rains vanish. Life falters. The myth speaks in symbols, but its meaning is chillingly real: without the storm god, the land starves. Drought stalks the fields. The gods themselves grow restless.

The Fox Steps Forward

Faced with catastrophe, Enlil calls a divine assembly. He does not act alone; the gods deliberate, paralyzed by their own impotence. Who among them will risk the journey into the kur to retrieve the storm god? Who will face the yawning darkness?

Only one steps forward—Fox.

It is a quiet moment of mythic inversion. The mighty gods hesitate. But a small, clever creature volunteers for a task that others fear. The fox is not just a character here but a symbol—the earliest surviving association of the fox with cunning and courage in Sumerian literature.

To enter the netherworld, Fox must follow its rules. The food and drink of the kur are forbidden, for to eat them is to be trapped forever. But Fox, in an act of brilliant subversion, accepts the offerings only to hide them in his receptacle. It is a moment of wit disguised as reverence. By pretending to partake while secretly abstaining, Fox preserves his freedom and opens a path for rescue.

And then the story breaks off.

The tablet, already fragmented when excavated, falls silent at this moment of tension. We do not know whether Fox succeeds. We are left with questions suspended in the clay—questions as old as the myth itself. Did Ishkur return with the rains? Was balance restored? Or did the netherworld claim him forever?

The Dance of Death and Rebirth

Even in its broken state, the narrative etched into Ni 12501 pulses with ancient symbolism. It belongs to a mythological pattern found across time and cultures: the disappearance of a deity who ensures fertility, followed by chaos, and finally restoration. In Egypt, Osiris descends into death and returns through Horus. In the Levant, Baal confronts Mot. In Greece, Persephone’s abduction brings winter to the earth.

In Sumer, the cycle may have been agricultural, spiritual, or both. The imagery in the opening—sparkling rivers, vibrant cows—could reflect the real-life bounty of the rainy season. Ishkur’s capture may signify the dry season or a specific drought remembered in song. His return, though unwritten, is implied by the structure of myth itself: loss must lead to recovery.

The narrative also holds the seeds of deeper reflection. That a fox, not a god, undertakes the rescue may suggest something profound about how the Sumerians viewed wisdom, humility, or the unpredictable agents of salvation. The helplessness of the gods is itself a curious motif—one that suggests that even divine powers are subject to cosmic law and the whims of the kur.

A Lost Masterpiece of Myth

What makes Ni 12501 so haunting is not only its content but its condition. Less than one-third of the original tablet survives. Its characters whisper rather than speak. Its story ends in silence. And yet, the fragments throb with meaning.

It is a tragedy of ancient literature that so much has been lost. Cuneiform tablets, despite being baked and resilient, remain vulnerable to erosion, war, looting, and decay. Myths like the one preserved on Ni 12501 likely once existed in fuller form, performed aloud in temples, inscribed in libraries, and passed down through generations. What we hold now are only glimpses—shards of a once-glowing stained-glass window.

Yet even in brokenness, the myth endures. Its characters—Enlil the king of gods, Ishkur the stormbringer, Fox the trickster—live on not just as religious figures but as archetypes. The motifs of fertility, death, cunning, and divine rescue echo throughout Mesopotamian and later traditions. The myth resonates because it speaks to timeless themes: the fragility of life, the terror of loss, and the hope that even in darkness, someone—something—will descend into the depths to bring life back again.

A Call for Further Discovery

Dr. Jana Matuszak’s study does more than reinterpret an old fragment; it reignites the urgency of archaeological exploration and textual preservation. So many Sumerian tablets remain unread, unedited, or miscatalogued. The myth of Ishkur and Fox might not be alone. Other copies could lie beneath ruins or sit mislabeled in museum drawers, waiting for new eyes and open minds.

And so, the story of Ni 12501 is not merely about the past. It is also about what lies ahead—the need to protect, study, and cherish the remnants of humanity’s earliest spiritual imagination.

Because in the end, myths are not just old stories. They are records of how our ancestors saw the world, how they endured hardship, and how they made sense of forces beyond their control. They are poetry carved in clay.

Ni 12501 may never reveal its full story. But in its fractured tale of divine loss, daring rescue, and quiet resilience, it reminds us of the depths we have yet to explore—not only in history, but within ourselves.

Reference: Jana Matuszak, OF CAPTIVE STORM GODS AND CUNNING FOXES: NEW INSIGHTS INTO EARLY SUMERIAN MYTHOLOGY, WITH AN EDITION OF NI 12501, Iraq (2025). DOI: 10.1017/irq.2024.19