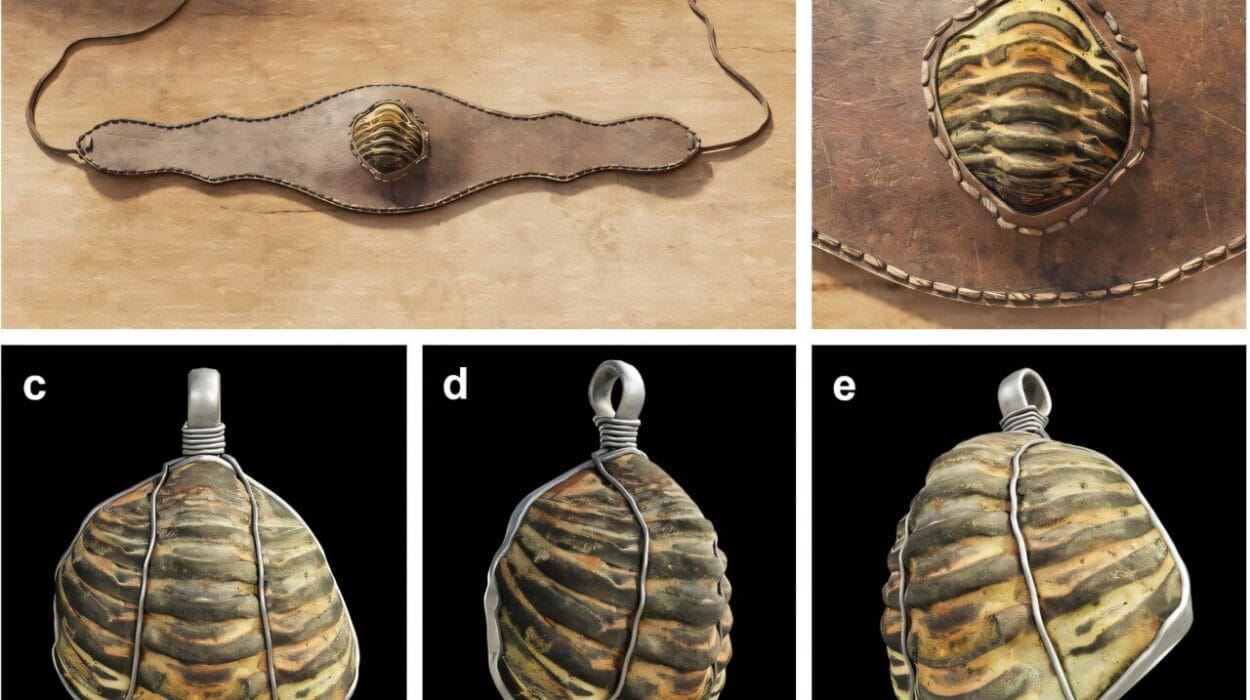

When Ötzi the Iceman was pulled from the melting ice of the Alps in 1991, he emerged not just as a body preserved for more than five millennia, but as a whispering ghost from a vanished world. His leathery skin, punctured by tattoos; his weapons, worn but intact; even the contents of his stomach—all offered a rare window into a life lived long before written language or empires. Yet, for decades, Ötzi stood alone in our imagination, a solitary sentinel from the past.

But history, like the ice that once entombed him, is beginning to melt open. A new genetic analysis of 47 individuals from the same Alpine region—spanning a time from 6400 to 1300 B.C.—has revealed that Ötzi’s world was far from isolated. His neighbors, their bones buried quietly in mountain soils for thousands of years, are now speaking too. And what they’re telling us is rewriting our understanding of early European ancestry and the surprising stability of the human story in this rugged stretch of Earth.

The DNA Map Hidden in Ancient Teeth

In a groundbreaking study published in Nature Communications, geneticist Valentina Coia and her colleagues extracted DNA from the remains of people who once lived in the Austrian Tyrol. Using bones and teeth as their time machines, they reconstructed the genomes of individuals who lived during the Mesolithic, Neolithic, and Bronze Ages. And in the process, they uncovered something unexpected: a remarkable genetic steadiness over two millennia.

The people who lived in this mountainous cradle weren’t genetic mosaics shaped by constant waves of newcomers, as was true for many parts of prehistoric Europe. Instead, their genomes revealed deep roots—showing that between 80% and 90% of their ancestry came from early Anatolian farmers, who migrated into Europe during the Neolithic period from what is now modern-day Turkey.

This finding stood in sharp contrast to what had been observed elsewhere on the continent, where successive influxes—from steppe pastoralists, hunter-gatherer remnants, and other migrating groups—left clear imprints on the DNA landscape. But in the Alps, change came slowly, if at all.

A Genetic Refuge in the Mountains

So why did the Eastern Alps remain so genetically stable while much of Europe experienced churn and change?

The answer may lie in the terrain itself. The Alps have always been a natural barrier—majestic, isolating, and often treacherous to cross. While they did not entirely shield their inhabitants from outside influence, they seem to have acted as a cultural and genetic buffer zone. Life in these highlands was hard, but it was also protective, preserving a way of life—and a gene pool—for far longer than in more accessible regions.

This continuity suggests that Alpine communities remained relatively self-contained for millennia. Generations of families may have lived, farmed, and died within sight of the same mountain peaks, passing their genes on with little interference from the wider world. Such genetic stillness speaks to the enduring strength of their traditions and the resilience of life in one of Europe’s most unforgiving environments.

The Iceman’s Ancestral Echo

Yet amid this stability, Ötzi himself stands out. His genome, first sequenced over a decade ago, revealed some curious differences. While he, too, shared ancestry with early Anatolian farmers, his paternal lineage—traced through the Y chromosome—did not match that of the 47 ancient individuals examined in this new study. They shared genetic markers commonly found in prehistoric populations from what is now Germany and France. Ötzi’s paternal line, however, was more widespread and bore fewer similarities to his neighbors’.

This distinction is not merely academic. It suggests that Ötzi may have come from a different lineage altogether, even though he lived within the same geographic region. Could he have been part of a group that was culturally or socially distinct from his neighbors? Perhaps he was a traveler, an outsider who settled in the Alps or was passing through when death found him high in the mountains.

More intriguingly, Ötzi’s maternal lineage—the markers passed through mitochondrial DNA—has not been found in any ancient or modern populations. He is, quite literally, a genetic ghost. Was his family line part of a small group that eventually disappeared? Or did Ötzi represent a branch of humanity that left no descendants?

These are not easy questions to answer. But they force us to reconsider the neat categories we often apply to ancient populations. The past, like the present, was messy. Full of migrations, mergers, extinctions, and surprises.

Women on the Move, Men Holding Ground

One of the subtler revelations of this research lies in the contrasting patterns of maternal and paternal DNA. While the male Y-chromosome lineages remained surprisingly consistent—indicating that men likely stayed in the regions where they were born—the maternal lines were more diverse.

This genetic signature hints at a cultural pattern common across ancient Europe: patrilocality. Men inherited land and remained rooted in place, while women left their birth communities to join their husbands’. It’s a story told not in texts, but in the slow shuffle of mitochondrial markers over generations. Behind it are lives lived and choices made—alliances between villages, marriages between clans, and the quiet power of maternal lines that carried their legacies across valleys and mountaintops.

This ancient gendered mobility reshaped communities in subtle ways. While men passed down land and status, women carried new blood and ideas from afar. The tension between rootedness and change played out not in battles or monuments, but in the very bones of those who lay buried beneath Alpine soil.

Dark Eyes, Dark Hair, and Empty Stomachs

Beyond ancestry, the study also shed light on the physical traits of these ancient mountain dwellers. In six of the genomes studied, enough high-quality DNA was preserved to predict pigmentation. The results aligned closely with what scientists had already concluded about Ötzi himself: these were people with dark eyes and dark hair. Far from the fair-haired stereotypes often associated with ancient Europeans, the inhabitants of the early Tyrol were more Mediterranean in appearance.

Another shared trait was less visible but just as telling: lactose intolerance. Despite their farming ancestry, these people could not digest milk in adulthood. The genetic mutation that allows most modern Europeans to drink milk without discomfort was still rare or absent among them. This suggests that dairy consumption—so central to many ancient economies—may not have included drinking raw milk, but rather the production of cheese and yogurt, where lactose levels are reduced.

It’s a subtle reminder that the past was not just different in culture or language, but in body and biology. The foods we eat without thinking today might have caused real pain for our ancestors.

A Solitary Death in a Shared World

As the evidence accumulates, a picture begins to form—not just of Ötzi, but of the world he knew. He was not alone, not a mysterious one-off figure frozen in ice and silence. He was part of a wider story, written across generations and buried beneath the soil of the Alps.

Yet even in this broader context, Ötzi remains an outlier. His unique maternal line, his differing paternal ancestry, and his lonely end on a high Alpine ridge still resist easy explanation. Was he a hunter betrayed? A trader who strayed too far from his path? A leader, an exile, or a victim of ancient violence? The arrowhead found lodged in his back suggests the end came suddenly—and not peacefully.

And still, we wonder.

The Mountains Remember

In the end, the story of Ötzi and his neighbors is not just one of genes and geography. It’s a story of continuity and change, of lives lived on the margins of ice and time. It is a story of people who endured, who passed down their blood and knowledge in a landscape that changed glacially, if at all.

The Alps watched them come and go, burying their bones, preserving their secrets. Only now, with the tools of modern science, are we beginning to hear them whisper again. DNA, once locked in marrow, speaks across time. It tells us that while Ötzi may have died alone, he was never truly alone in life.

In the cold embrace of the mountains, the past is never far away. It waits, preserved in silence, until the right moment comes—and then, like a mummy in the ice, it rises and speaks.

Reference: Myriam Croze et al, Genomic diversity and structure of prehistoric alpine individuals from the Tyrolean Iceman’s territory, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-61601-8