Beneath the sands of Egypt, the jungles of Central America, the mountains of Turkey, and the oceans themselves, lie whispers of ancient worlds. Civilizations long gone, names forgotten, languages silenced—yet their traces remain. Enormous stone monuments that align perfectly with celestial bodies. Underground cities carved with impossible precision. Megaliths weighing hundreds of tons moved without modern machines. Myths that echo across continents, telling strangely similar tales of floods, stars, gods, and knowledge from the skies.

To the casual observer, these wonders are relics—quaint artifacts of a less advanced time. But to many archaeologists, scientists, and independent researchers, they are puzzles begging to be reassembled. Did ancient civilizations know more than we’ve given them credit for? Did they develop scientific, astronomical, and engineering knowledge far beyond what we’ve assumed? And if so, how did they acquire it—and why did they lose it?

The past is not a simple story of progress. Sometimes, it’s a tale of brilliance lost and rediscovered. And the truth, emerging from excavation sites and ancient texts alike, is far more astonishing than we imagined.

The Engineering That Shouldn’t Exist

One of the most striking challenges to our understanding of ancient knowledge is the scale and precision of construction in the distant past. The pyramids of Egypt are the poster child of this mystery, but they are far from alone.

Consider the Great Pyramid of Giza. Built around 2560 BCE, it stood as the tallest man-made structure for nearly 4,000 years. The precision of its alignment with true north is unmatched by modern buildings. The limestone casing stones, now mostly gone, were cut to such exact tolerances that even a human hair couldn’t be inserted between them. Some internal granite blocks weigh as much as 80 tons. The question is not only how they were transported, but how they were placed so accurately.

Mainstream Egyptologists have proposed ramps, pulleys, and huge labor forces, and while these are plausible, they leave lingering doubts about feasibility. There’s no definitive evidence of the massive ramps such a project would require. Some physicists and engineers have called for a reevaluation, suggesting that we may be underestimating ancient Egyptian knowledge of physics and mathematics.

And Egypt is just the beginning. In Peru, the Inca city of Sacsayhuamán features stone walls made from irregularly shaped rocks, some weighing over 100 tons, fitted together like a 3D jigsaw puzzle—without mortar. The stones lock into place so tightly that not even a knife blade can slip between them. The craftsmanship is astonishing, and so is the question: why build this way if not to withstand earthquakes, which the structures have done for centuries?

Then there’s the underwater site of Yonaguni, near Japan, which appears to show terraced, staircase-like structures submerged beneath the ocean. Are these natural formations, as some geologists believe? Or are they remnants of a lost civilization, as others argue?

The debate continues. But one thing is clear: ancient people were not primitive. They were observant, resourceful, and, in some cases, technologically sophisticated in ways we are only beginning to understand.

Stargazers of Stone and Fire

In the high Andes, the ancient city of Tiwanaku once flourished near the shores of Lake Titicaca. Its centerpiece, the Kalasasaya temple, is aligned with the solstices and may have served as an astronomical observatory. Some researchers argue it was used to track the movements of Venus, a planet revered by many ancient cultures. The temple’s layout suggests an understanding of the solar year and even leap years.

This is not an isolated example. Across the globe, ancient sites show an eerie familiarity with the skies.

Stonehenge in England is famously aligned with the summer solstice sunrise. But less well-known is Nabta Playa, a site deep in the Egyptian desert predating Stonehenge by at least a thousand years. Its stone circle appears to mark solstices and the rising of Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky.

In Mesoamerica, the Maya built cities aligned to celestial events with mathematical accuracy. Their calendar systems, especially the Long Count, are feats of intellectual brilliance. They predicted solar eclipses and charted planetary orbits. And they did it all without telescopes or metal tools.

Why did these civilizations care so deeply about the sky? Partly, it was spiritual. The heavens were gods’ realms. But it was also scientific: stars told them when to plant, when to harvest, when rains would come, and when to fear disaster. Their survival depended on it. And their knowledge was codified in monumental architecture, myth, and ritual.

Modern archaeoastronomy, the study of ancient astronomy through archaeological sites, is revealing just how widespread and complex this celestial obsession was. From Angkor Wat in Cambodia to Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, patterns emerge. Ancient people were not passively gazing at the stars—they were studying, recording, and building with them in mind.

The Mythic Memory of Catastrophe

The oldest stories we have are myths, but myths are not meaningless. They are vessels of memory. And one recurring motif found in dozens of ancient cultures is that of a great flood—a deluge that wiped out a previous age of civilization.

The Sumerians, among the world’s earliest known civilizations, told of a flood hero named Ziusudra. The Akkadians knew him as Atrahasis. The Babylonians retold the story in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Then, of course, there is Noah in the Hebrew Bible. In India, there’s Manu, the first man saved from a flood by a god in the form of a fish. The Greeks had Deucalion. The Chinese had Nuwa. The Aztecs had Coxcox.

Why do so many ancient people, separated by oceans and millennia, share the same core story?

One possibility is shared trauma. Around 10,800 BCE, Earth experienced a sudden cooling event known as the Younger Dryas, possibly triggered by a comet or massive volcanic activity. At the end of this period, sea levels rose rapidly—perhaps due to melting glaciers or an impact-induced flood. Entire coastal settlements would have been swallowed. The memory of that catastrophe may have passed down orally, evolving into myth.

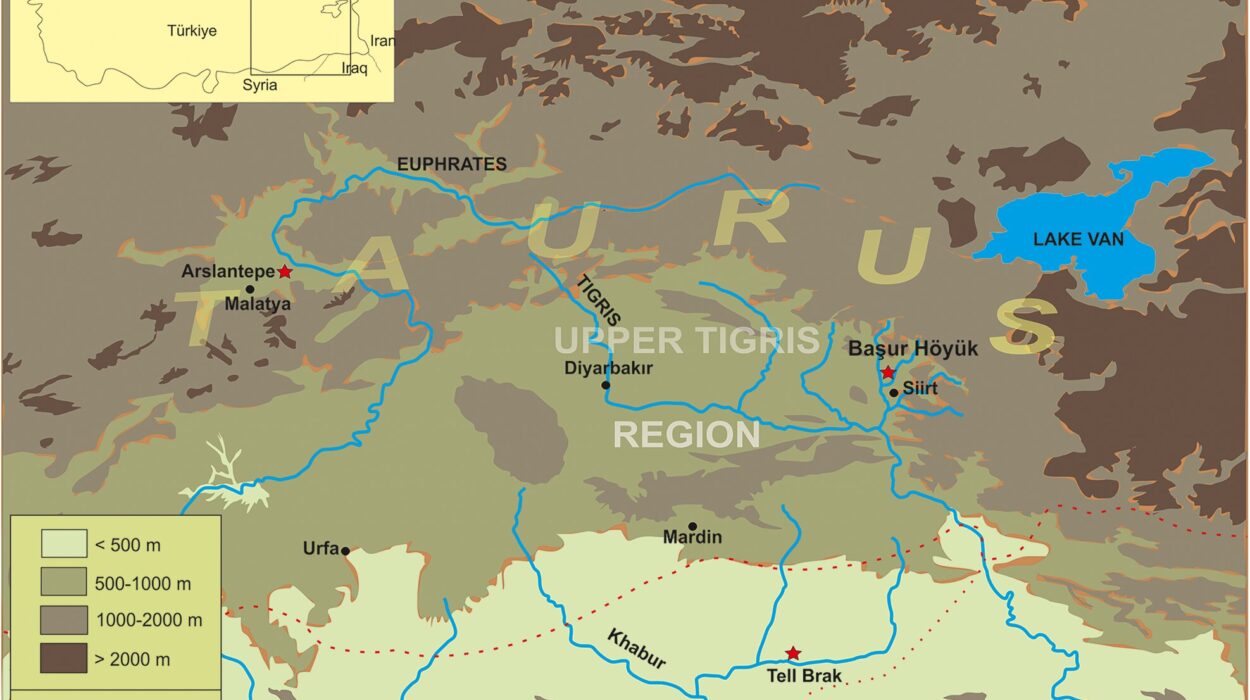

Some researchers argue that human civilization is older than we’ve documented—and that a global disaster erased its earliest chapters. Sites like Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, dated to 9600 BCE, support this view. Its stone circles predate agriculture, writing, and the wheel. They show artistic complexity and astronomical alignment—and yet were deliberately buried, for reasons unknown.

Göbekli Tepe changed the timeline of civilization. If more sites like it are uncovered, we may be forced to rethink our entire understanding of human history.

Maps That Shouldn’t Exist

In the 16th century, a Turkish admiral named Piri Reis created a map that baffled cartographers for centuries. It accurately depicts the coastlines of South America and Africa—with incredible precision for its time. But the real mystery lies in its apparent rendering of Antarctica—before it was officially discovered.

Even more oddly, the map appears to show the continent without its current ice cover. Some scientists suggest this would only have been possible thousands of years ago, based on ice core data.

Skeptics argue the resemblance to Antarctica is coincidence. But the map raises another question: how did early mapmakers, who lacked satellite technology, chart global coastlines with such accuracy?

Some suggest ancient mariners were more capable than we thought, sailing and mapping the world long before Columbus or Magellan. Others believe ancient knowledge—perhaps from a forgotten seafaring culture—was passed down through centuries, eventually reaching Renaissance Europe.

This theory isn’t far-fetched. Polynesians navigated thousands of miles using star charts, wave patterns, and bird behavior. The Vikings reached North America long before Columbus. Why couldn’t others have done the same?

The Language of the Gods

Ancient texts often refer to knowledge bestowed by divine or semi-divine figures. The Sumerians spoke of the Anunnaki, beings from the heavens who taught them agriculture, mathematics, and law. The Egyptians had Thoth, the god of wisdom and writing. The Mayans revered Itzamna, a sky-god who brought writing, calendars, and medicine.

Are these just metaphors, personifying human invention? Or could they reflect cultural memories of lost knowledge—perhaps even contact with a more advanced civilization?

While ancient aliens make for compelling TV, most scientists reject extraterrestrial explanations. But that doesn’t mean the truth isn’t strange in its own way. Perhaps early civilizations had isolated centers of advanced knowledge—mathematicians, astronomers, engineers—whose impact echoed far beyond their time. As their cities fell and libraries burned, the survivors became mythologized as gods.

Consider the Library of Alexandria, which may have held tens of thousands of scrolls. Its destruction, through fire and neglect, erased centuries of human knowledge. Now imagine that happening a thousand years earlier, to a city we’ve never found.

What would remain? Myths. Symbols. Puzzles carved in stone. A knowledge too fragile to survive—but too extraordinary to forget.

What Science Is Starting to Say

Modern science is catching up to some of these mysteries—not by embracing pseudoscience, but by applying better tools. Satellite imagery and LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) have revealed entire lost cities beneath jungles in Cambodia and Guatemala. Ground-penetrating radar is uncovering hidden tombs in Egypt. Deep-sea exploration is mapping sunken settlements in the Mediterranean and beyond.

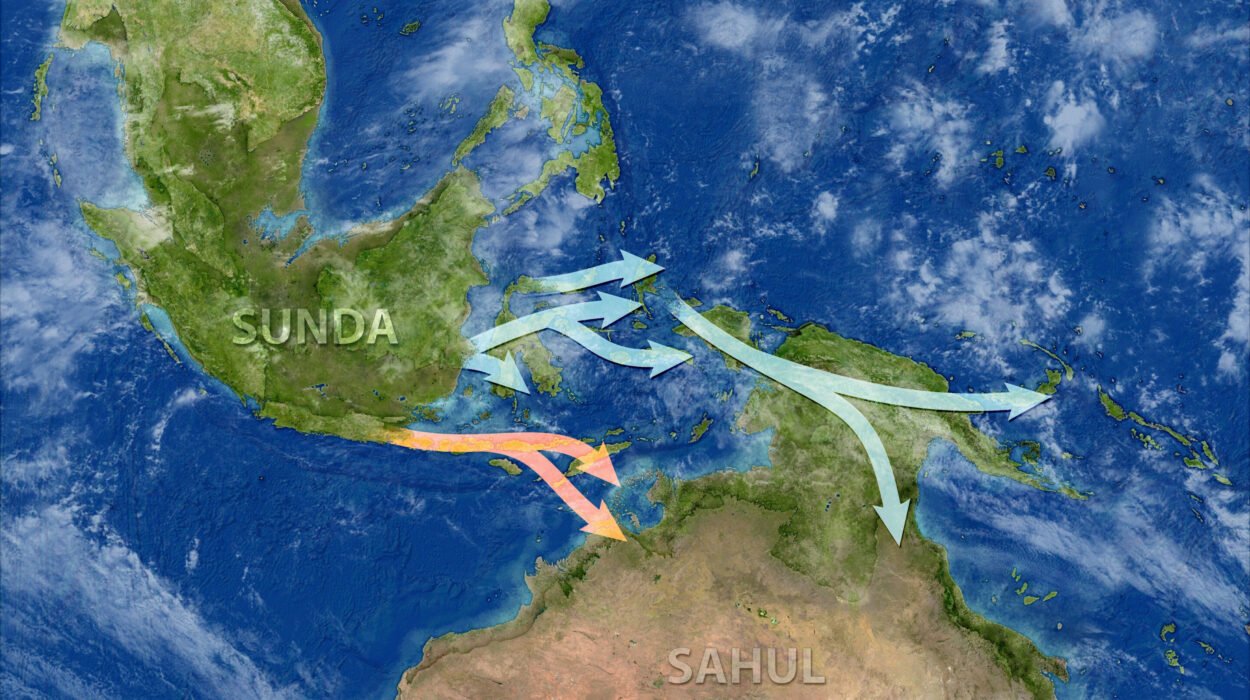

Genetic studies are also illuminating ancient migration patterns. The idea that civilization began in a single cradle—Mesopotamia, Egypt, or China—is being replaced by a more complex picture. Human groups developed agriculture, writing, and cities independently in different parts of the world. Sometimes they rose in tandem, other times they fell into darkness, only for others to rediscover the light.

Archaeology, once focused on artifacts alone, now incorporates climatology, linguistics, satellite data, and DNA. It’s painting a richer, more interconnected picture of ancient humanity—and it hints at how much we’ve lost.

We now know that complex societies existed in the Amazon basin, once thought too harsh for civilization. Massive earthworks and road systems prove otherwise. Similarly, massive temple complexes in Indonesia and India may be far older than once believed.

The scientific community is slowly accepting that ancient people were not just capable—they were extraordinary. The more we dig, the more we find.

The Memory of Fire and Stars

So, did ancient civilizations know more than we think?

Yes—though perhaps not in the way fringe theories imagine. There is no need for ancient astronauts or time travelers. The truth is remarkable enough.

They knew the cycles of the Earth and sky. They understood geometry and proportion. They engineered marvels with stone, bronze, and sweat. They memorized and passed down knowledge without paper or code. They told stories that carried truth in metaphor, myth, and symbol.

They watched the stars and saw patterns. They watched the seasons and built calendars. They listened to the world in ways we have forgotten.

And when the waters rose, the empires fell, and the scrolls burned, what remained were stone and story.

Echoes in the Dust

We stand on the shoulders of forgotten giants. In the ruined cities and broken tablets, in the rhythms of ancient chants and the angle of a shadow on a solstice, we glimpse a truth: knowledge is not a straight line. It is a spiral, winding through ages of light and dark, discovery and loss.

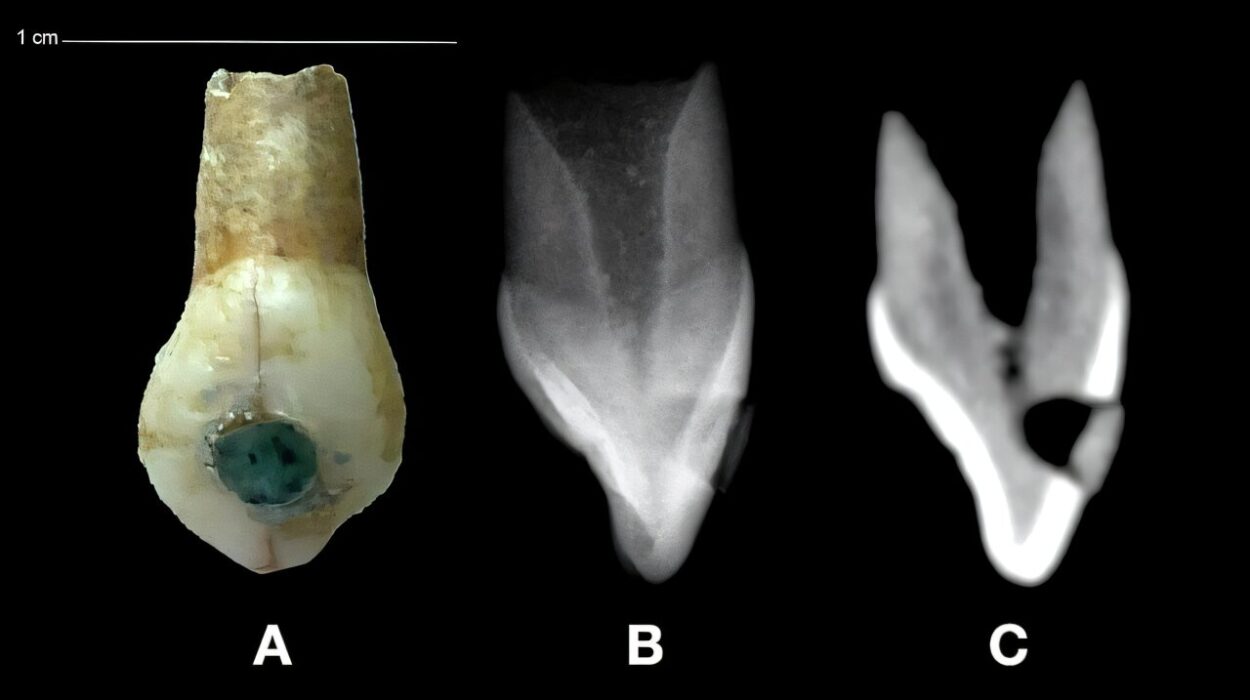

Every excavation uncovers not just artifacts, but evidence of minds as curious, clever, and creative as our own.

So, the next time we marvel at a smartphone, a space telescope, or a skyscraper, let’s also remember those who once looked to the same stars—and built wonders from stone.

Their civilizations may have crumbled, but their minds still speak to us. Not with words, but with questions.

And those questions are still waiting to be answered.