Depression is one of the most common and devastating mental illnesses in the world. It can arrive quietly or suddenly, disrupting lives, relationships, and ambitions. Yet despite its widespread impact, depression remains deeply complex—its causes a tangled web of genetics, biology, and life experience. Now, a groundbreaking study published in Nature Genetics is helping scientists untangle part of that web, revealing that not all depressions are created equal.

Researchers from Karolinska Institutet and several Nordic universities have uncovered clear genetic differences between depression that begins early in life and depression that develops later on. Their findings suggest that depression emerging before the age of 25—often the most vulnerable and formative years—has a much stronger hereditary component than depression that begins later in adulthood. Even more concerning, this early-onset form of depression is closely tied to a higher risk of suicide attempts.

This discovery sheds new light on why some young people struggle so profoundly with mental illness—and could help shape the future of suicide prevention and personalized psychiatric care.

Tracing the Genetic Blueprint of Depression

The study, titled “Genome-wide association analyses identify distinct genetic architectures for early-onset and late-onset depression,” examined genetic and medical data from more than half a million people across five Nordic countries: Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Estonia.

Among these were over 150,000 individuals diagnosed with depression and 360,000 controls without the condition. By dividing the data into two key groups—those who experienced their first major depressive episode before age 25, and those diagnosed after age 50—the researchers were able to compare the genetic architecture of early-onset and late-onset depression with unprecedented precision.

What they found was striking. The genetic fingerprints of these two types of depression were clearly distinct. Twelve specific genetic regions were associated with early-onset depression, while only two were linked to the late-onset form. This suggests that early and late depression are not merely the same illness occurring at different times, but rather two overlapping disorders with unique biological foundations.

According to Lu Yi, senior researcher at Karolinska Institutet and one of the study’s corresponding authors, the discovery represents an important step toward more targeted mental health care. “We show that early-onset depression has partly different genetic causes than depression that affects older individuals and that the risk of suicide attempts is increased,” Yi explained. “This is an important step toward precision medicine in psychiatry, where treatment and preventive measures are tailored to each individual.”

The Genetic Shadow of Early-Onset Depression

Depression in youth and young adulthood is particularly devastating because it strikes during a period of identity formation, education, and emotional development. The new findings reveal that the genetic component in these early cases is both powerful and dangerous.

One in four people with a high genetic risk for early-onset depression attempted suicide within ten years of their first diagnosis. That rate is roughly double that of individuals with a lower genetic risk, suggesting that genes may play a stronger role not only in the emergence of the illness but also in its severity and life-threatening consequences.

This raises a sobering reality: for many young people, depression is not simply a reaction to life’s pressures or trauma. It is, at least in part, an inherited vulnerability deeply encoded in their DNA—one that can shape brain chemistry and emotional regulation long before symptoms appear.

Still, genes are not destiny. Environmental factors such as social support, therapy, access to healthcare, and early intervention remain crucial in determining outcomes. But understanding genetic risk could allow doctors to identify those who need the most intensive care and follow-up before a crisis occurs.

The Science Behind the Findings

Depression is already known to be influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, but teasing apart their contributions is notoriously difficult. The scale and scope of this Nordic study give it unique power to detect subtle genetic signals that smaller studies could not.

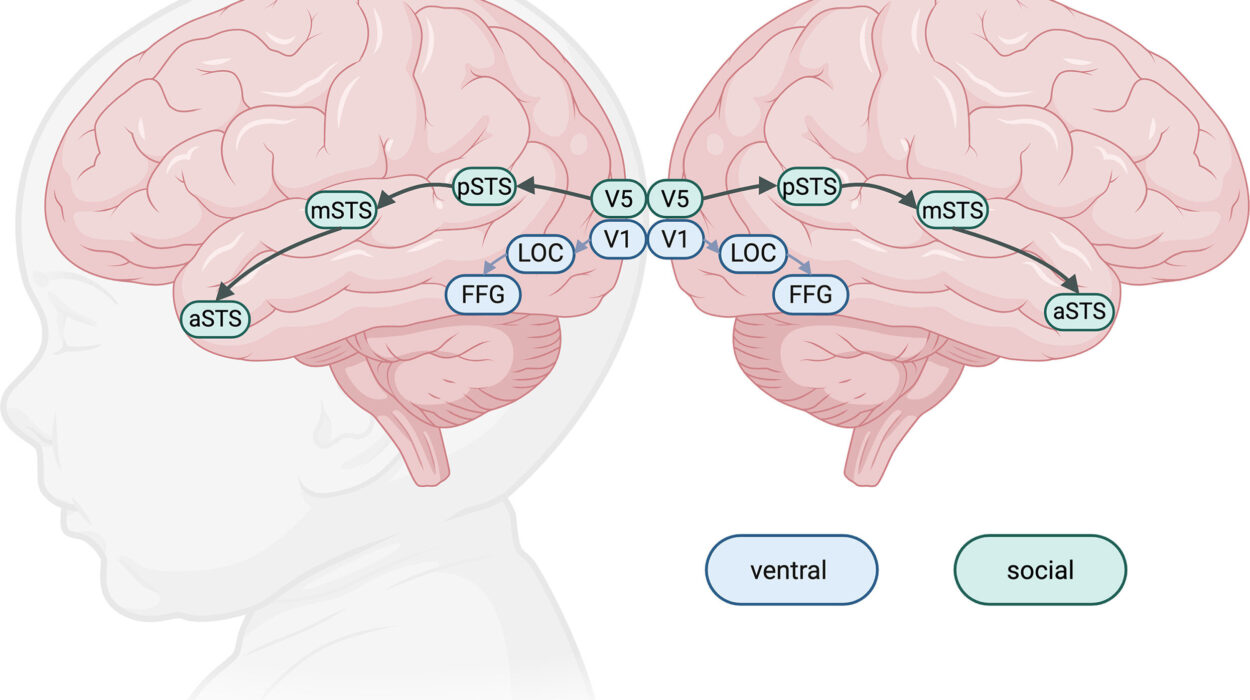

By using genome-wide association analyses, researchers scanned millions of points in the human genome, searching for variants more common in people with depression than in those without it. These “genetic markers” point to biological pathways involved in mood regulation, stress response, and brain development.

The team’s discovery of twelve regions strongly linked to early-onset depression suggests that these individuals may have heightened sensitivity in brain circuits that control emotion and reward. Some of the implicated genes are believed to affect how neurons communicate and how the brain processes stress—factors that could make young individuals more susceptible to intense emotional pain and suicidal thoughts.

In contrast, the two regions associated with late-onset depression may reflect biological processes that accumulate with age—such as changes in inflammation, vascular health, or hormonal systems—making depression in later life a fundamentally different condition.

The Human Cost Behind the Data

Beyond the statistics lies a human story—a story of struggle, silence, and resilience. Depression that begins in youth often robs people of their brightest years. It can interfere with education, relationships, and self-discovery, leaving lasting scars. For many, it is not just sadness, but an invisible weight that distorts reality and drains meaning from life.

The new research underscores that these experiences are not signs of weakness. They are rooted, at least in part, in biology—a reminder that mental illness is as real as any physical disease. Knowing that genetic factors play such a strong role could help reduce stigma, shifting the conversation from blame to understanding and compassion.

But the study also highlights an urgent need: prevention. If healthcare systems can identify those with high genetic risk early—perhaps even before the onset of symptoms—they could provide extra support, therapy, and monitoring to prevent the tragedy of suicide.

Toward Precision Psychiatry

The field of psychiatry has long lagged behind other branches of medicine in using genetic data to guide treatment. But that may soon change. As scientists map the genetic underpinnings of mental disorders, the idea of precision psychiatry—tailoring care to an individual’s genetic and biological profile—is moving closer to reality.

The researchers at Karolinska Institutet and their collaborators hope that genetic insights will one day help doctors predict who is most at risk, choose treatments more effectively, and prevent suicidal behavior. “We hope that genetic information will be able to help healthcare professionals identify people at high risk of suicide, who may need more support and closer follow-up,” says Lu Yi.

By linking genetics with medical history, brain imaging, and environmental data, scientists aim to build risk profiles that can guide interventions before the illness becomes severe. This could transform mental health care from reactive to proactive—from crisis response to early protection.

Understanding the Brain Through Genes

The next phase of research will explore how these genetic differences shape the brain itself. Scientists want to know how early-onset depression genes influence brain development, stress sensitivity, and emotional regulation. Do they affect how brain circuits form in adolescence? Do they change how the brain responds to trauma or loss?

Answering these questions will require integrating genetics with neuroscience—mapping how DNA shapes the biology of emotion. Researchers also plan to study how life experiences interact with genetic predispositions, since stress, social isolation, and childhood adversity can amplify the risk for depression, even in those without strong hereditary factors.

Hope in Knowledge

The discovery that early-onset depression has its own genetic fingerprint is both alarming and hopeful. It reveals how deeply biology shapes our emotional world, but also how understanding that biology can help us protect it.

For countless young people, depression is a silent storm. But studies like this one remind us that knowledge itself can be a lifeline. By revealing the hidden architecture of mental illness, science brings us closer to a future where no one has to face that storm alone.

A Future Without Guesswork

The vision is clear: a world where a young person showing early signs of depression could be screened for genetic risk, given personalized treatment, and surrounded with the support they need before thoughts of self-harm ever take hold.

While that future is still on the horizon, it is now within sight. Every discovery—every gene mapped, every mechanism understood—brings us closer to transforming how we understand, diagnose, and heal the human mind.

In the quiet corridors of research labs across the world, scientists are decoding the invisible signatures written in our DNA. And in doing so, they are not only uncovering the roots of despair but planting the seeds of hope.

More information: Genome-wide association analyses identify distinct genetic architectures for early-onset and late-onset depression, Nature Genetics (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41588-025-02396-8.