Long before the First Emperor of China raised his mighty armies and declared the unification of a vast land, another kind of union was taking shape — quiet, sacred, and deeply human. Beneath the soil of Shandong Province, archaeologists have uncovered the physical remains of gatherings that tell a story not of conquest, but of connection.

Three ancient ritual platforms, dating back nearly 3,000 years, have been unearthed at the site of Qianzhongzitou, revealing how ceremonies, shared meals, and collective acts of worship sowed the first seeds of what would one day become the Chinese nation. The discovery, reported in Antiquity, invites us to rethink the origins of unity in China — not as a top-down decree from an emperor, but as something that grew from the earth upward, through the shared heartbeat of its people.

Before the First Emperor

In schoolbooks and monuments, China’s unification is often attributed to Qin Shi Huang, the formidable founder of the Qin dynasty, who in 221 BC brought warring kingdoms under one rule. He is celebrated for standardizing writing, currency, and measurements, and for initiating massive infrastructural projects — including the first version of the Great Wall.

Yet, as Dr. Qingzhu Wang of Shandong University explains, this unification did not appear overnight. “The First Emperor’s political unification of China marked the culmination of a long process,” Dr. Wang says. “That process was characterized by infrastructural investments, new technologies, and the integration of diverse ideological constructs.”

In other words, the emperor’s empire was built on a foundation laid long before his birth. And at Qianzhongzitou, archaeologists believe they have found evidence of the earliest moments when different peoples began to see themselves as part of something larger — a shared cultural and spiritual identity.

From Village to Sacred Center

The site of Qianzhongzitou lies in Shandong Province, a region long regarded as a cradle of Chinese civilization. For thousands of years, communities thrived there, cultivating the land, crafting tools, and building traditions that echoed across generations.

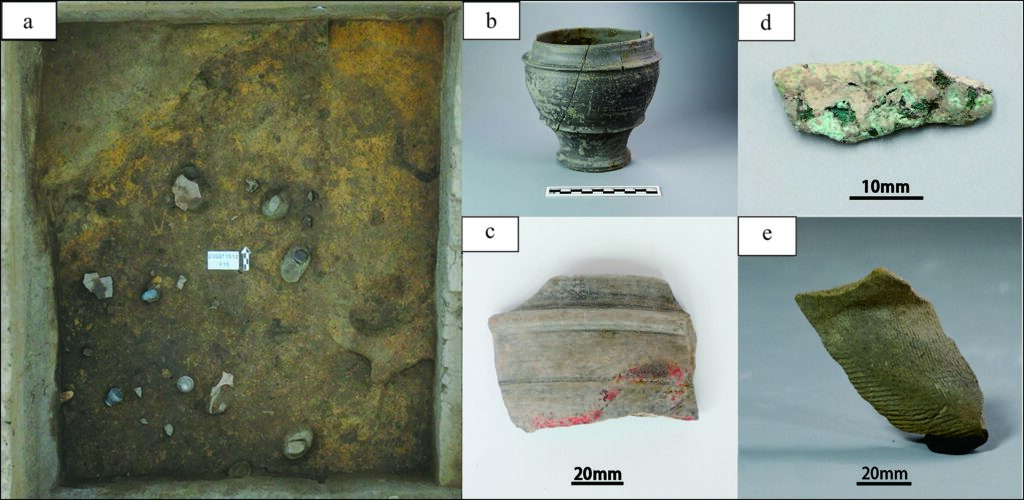

But over time, this once-humble village evolved into something greater — a ritual center, a place where communities gathered not just to survive, but to celebrate and connect with the divine. Excavations led by researchers from Shandong University and the Field Museum of Natural History in the United States revealed that the site transformed from a residential settlement into a ceremonial landscape of monumental platforms and sacred spaces.

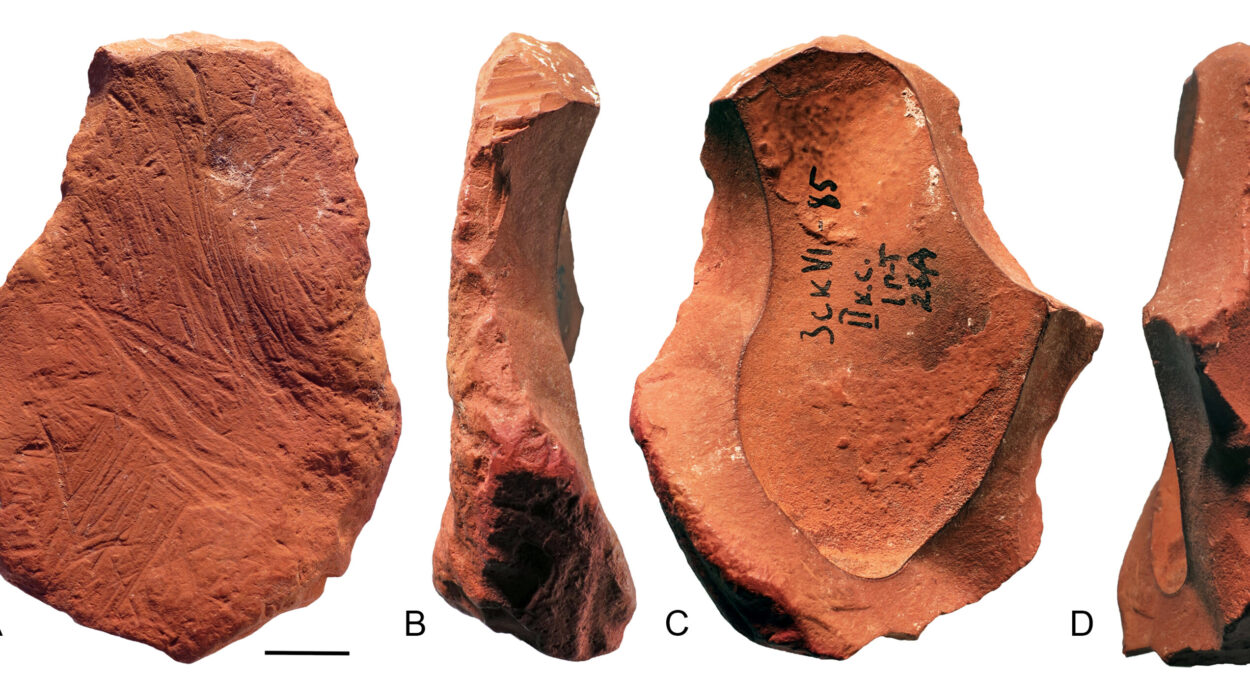

These platforms — some dating back to the Western Zhou period (c. 1046–771 BC) and others to the Warring States period (c. 475–221 BC) — were built with meticulous care. Layers of earth, each a different color, were compacted and shaped into wide, elevated structures. They were not merely functional — they were symbolic.

The Worship of Earth

Among the most striking discoveries were inscriptions of the Chinese character 土 (tǔ), meaning “earth,” carved or marked into one of the platforms. The character itself, simple yet profound, reflects humanity’s oldest reverence: the soil beneath our feet.

The colorful layers of earth, combined with these inscriptions, strongly suggest that these spaces were used for earth worship — rituals that honored the land as both a giver of life and a sacred power.

It is easy to imagine ancient communities gathering on these platforms, perhaps under the open sky, offering grain, pottery, or cooked food to the spirits of the land. Fires might have flickered, drums might have echoed, and the scent of roasted meat might have drifted through the air — signs of a great communal feast.

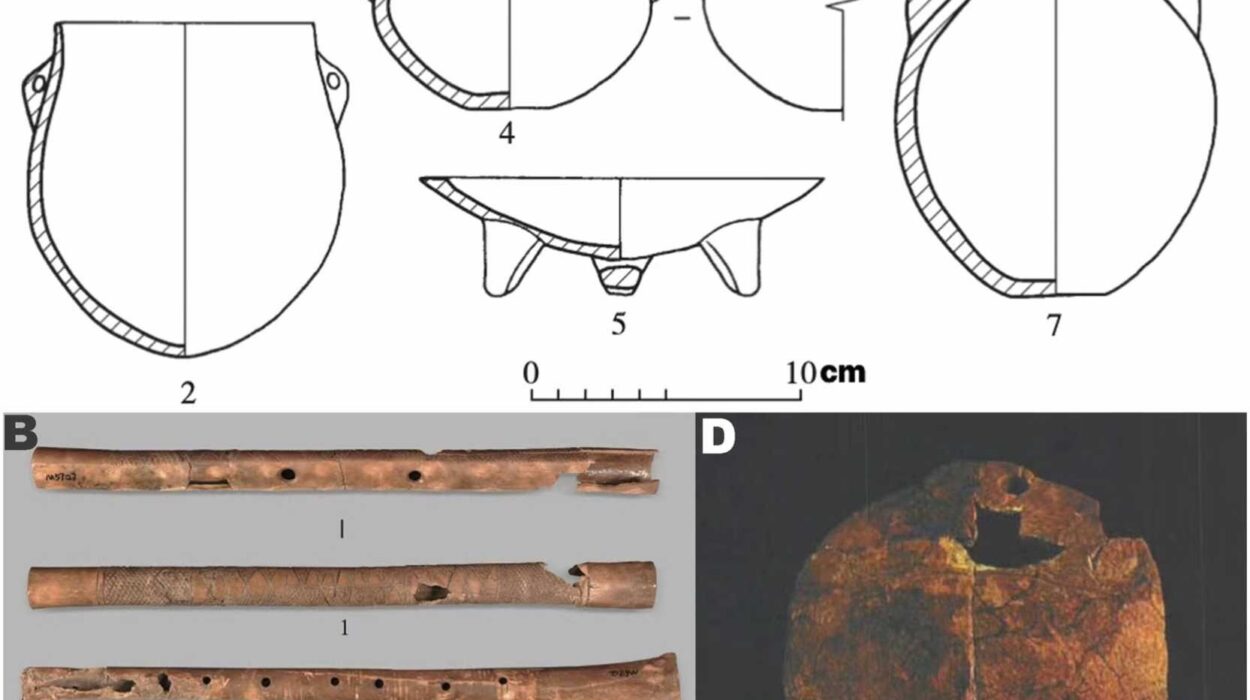

Indeed, archaeologists found cooking vessels and food remains around the platforms, evidence that ritual and feasting were inseparable. These were not private ceremonies of elites but public gatherings, where ordinary people participated in a shared act of devotion and identity.

Feasts of Faith and Identity

The power of these gatherings went beyond the spiritual. As Dr. Wang and his team suggest, such feasts and ceremonies were crucial for creating unity among diverse peoples. When hundreds gathered to eat from the same fires and bow before the same altars, they reaffirmed a shared belonging.

“The primary purpose of these platforms,” Dr. Wang explains, “was to bring together an expanding population and cultivate new collective identities through shared ritual experience.”

In this light, the platforms at Qianzhongzitou were not merely religious sites — they were the heartbeats of early community life. Through ritual, people negotiated power, expressed loyalty, and learned to see themselves as part of a greater whole.

These rituals became a social technology — a means by which local leaders and emerging states could bind people together not by force, but through shared belief and participation.

From Local Cults to State Beliefs

As ancient Chinese states expanded during the Zhou and Warring States periods, rulers faced the challenge of integrating diverse communities — each with its own traditions, gods, and ancestors. The findings at Qianzhongzitou show how local cults were not simply suppressed or replaced; they were absorbed and transformed into larger, state-sanctioned religious systems.

Historical records describe how the Qi State, which dominated northern and eastern Shandong, established a formal system of worship centered on the “Eight Deities” — the spirits of Heaven, Earth, the Sun, Moon, Yin, Yang, Arms, and the Four Seasons. These deities symbolized the balance and harmony of the universe, reflecting the state’s vision of cosmic and political order.

The ritual platforms at Qianzhongzitou likely represent an early stage in this transformation — when local worship of natural spirits, like that of the earth, began to merge with emerging state ideologies. These gatherings and ceremonies became prototypes of the grand, state-sponsored rituals that would later define imperial China.

In essence, the people of Qianzhongzitou were not only worshipping the earth — they were helping to build the foundation of Chinese civilization itself.

The Bottom-Up Revolution

Most histories of early China focus on the great rulers, the wars, and the monumental structures — the walls, palaces, and armies that shaped empires. But this research flips that narrative. By taking what the authors call a “bottom-up” approach, it shows that the real unification began at the community level.

It was through these public rituals, through music, food, and shared reverence, that people learned to live under shared symbols and beliefs. Over generations, these local traditions created the cultural cohesion necessary for larger states — and eventually, a single empire — to emerge.

The unification of China, then, was not only a political achievement but also a cultural awakening, built slowly through the collective experience of countless ordinary people.

The Power of Ritual

Modern life often separates politics from religion, community from ceremony. But in the ancient world, these boundaries did not exist. Ritual was the glue that held society together — a language that everyone could understand, regardless of tribe or dialect.

At Qianzhongzitou, ritual was not just performance; it was transformation. Each ceremony reaffirmed a shared worldview: that humans were part of a larger cosmic order, rooted in the cycles of the earth. Each gathering forged new bonds — of kinship, loyalty, and faith.

It was, in a sense, the earliest expression of what it meant to be Chinese — not as a political label, but as a shared spiritual and cultural identity.

Beyond Conquest

Dr. Wang summarizes the significance of the discovery poignantly: “Our excavations at Qianzhongzitou reveal that the expansion of ancient Chinese states went beyond military conquest. Elites strategically utilized grand public rituals and feasting on monumental platforms to integrate diverse peoples and their spiritual beliefs, cultivating a shared identity that helped form powerful states.”

This insight changes the way we view the origins of civilization. Empire did not rise only from the sword, but from the bowl — from shared meals, shared songs, and shared symbols. It was the soft power of ritual, not just the hard power of armies, that united early China.

A Legacy Written in Soil

As the archaeologists brushed away the final layers of soil at Qianzhongzitou, they uncovered not just earth and pottery, but a story — a story of how humans, long before they called themselves Chinese, gathered to celebrate life, honor the land, and find unity in difference.

The colored layers of the platforms are more than just architecture; they are metaphors for civilization itself — many hues, many origins, compressed into a single structure that endures through time.

Today, thousands of years later, modern China still stands on that same principle: that strength comes not only from power, but from shared identity. The echoes of those ancient feasts, those songs and offerings to the earth, still linger in the cultural DNA of a nation.

And perhaps, as we look upon these ancient ritual grounds, we are reminded of something timeless — that human unity, whether in the past or in the present, begins not with domination, but with gathering.

The Roots of a Civilization

The discoveries at Qianzhongzitou remind us that the great narrative of China — one of the world’s oldest and most continuous civilizations — began with something profoundly human: the desire to come together.

Before the walls and armies, before emperors and dynasties, there were gatherings beneath the open sky. There was music and firelight, shared food and laughter, reverence and belonging. From these rituals of earth and spirit grew the first sense of “we,” the first fragile thread of what would become a vast and enduring tapestry of identity.

The platforms of Shandong are silent now, their ceremonies long ended. Yet, within their layers of earth lies the memory of unity — the heartbeat of a civilization that learned, thousands of years ago, that the path to greatness begins with a shared offering to the earth beneath our feet.

More information: Zhou period transformations at the Qianzhongzitou site (Gaomi, Shandong, China), Antiquity (2025). doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10156