On the lush Danish island of Falster, the soft hum of modern machinery churning for a railroad expansion unexpectedly collided with the deep past. Beneath layers of soil and time, construction crews uncovered something utterly unexpected—an ancient puzzle of wood, loam, and stone that whispered of ingenuity more than five millennia old.

What they found at Nygårdsvej 3 wasn’t just another archaeological site dotted with flint shards and worn pottery. It was something more astonishing: a meticulously paved, subterranean structure that appeared to be a stone-lined root cellar—built over a thousand years before the Egyptian pyramids and more than 4,000 years before electricity and refrigeration would offer food preservation by modern means.

For archaeologists from Museum Lolland-Falster and Aarhus University, the site became a rare window into a critical period of human transformation in northern Europe. Their study, recently published in the journal Radiocarbon, reframes our understanding of Neolithic Scandinavia, pushing back the timeline of architectural and agricultural innovation with silent, stone-paved authority.

Funnel Beakers and the Agricultural Revolution in the North

To grasp the full weight of this discovery, one must first understand the Funnel Beaker Culture—a Neolithic farming society that rose across northern Europe around 4000 BC. These people, named after their distinctive funnel-shaped pottery, ushered in a seismic shift in Scandinavian life: they domesticated animals like cattle, sheep, and goats, cultivated cereals, and began building permanent dwellings.

Gone were the fluid migratory rhythms of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. In their place came sedentary village life, with megalithic tombs, wooden longhouses, and the first structured attempts to manipulate the land—often with lasting consequences.

It’s within this cultural cradle that the Nygårdsvej site emerges. Radiocarbon dating places its construction between 3080 and 2780 BC, situating it squarely within the middle of the Neolithic period. But what makes this site exceptional is not simply its age—it’s the technology embedded in its soil.

A Cellar Before Its Time

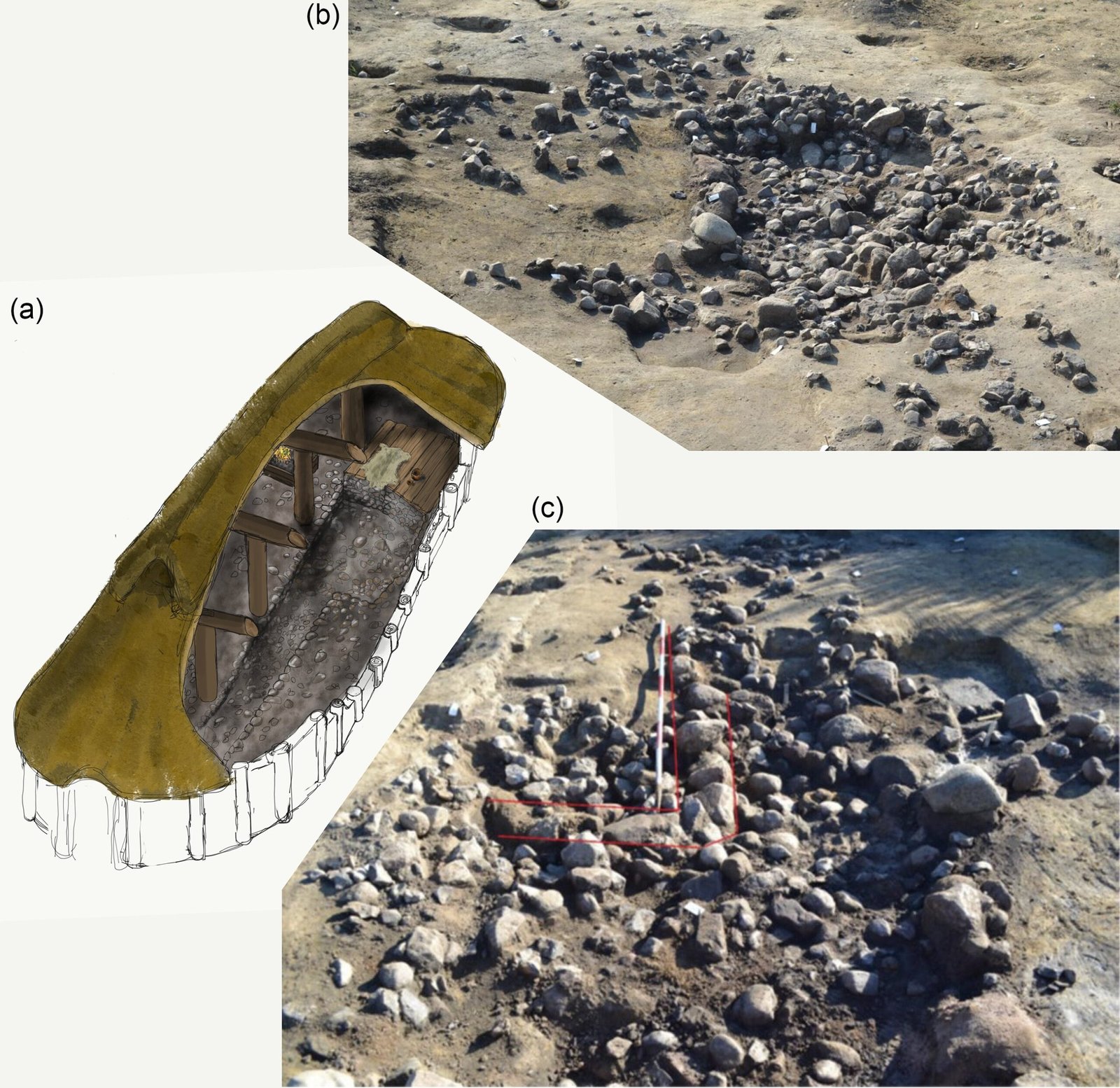

At first glance, the paved, sunken feature at Nygårdsvej 3 might have seemed like nothing more than a curious depression filled with ancient debris. But closer inspection revealed a carefully constructed floor lined with stones, set in an intentional pattern. The stones were not randomly scattered—they were deliberately placed, a flooring system reminiscent of a modern root cellar.

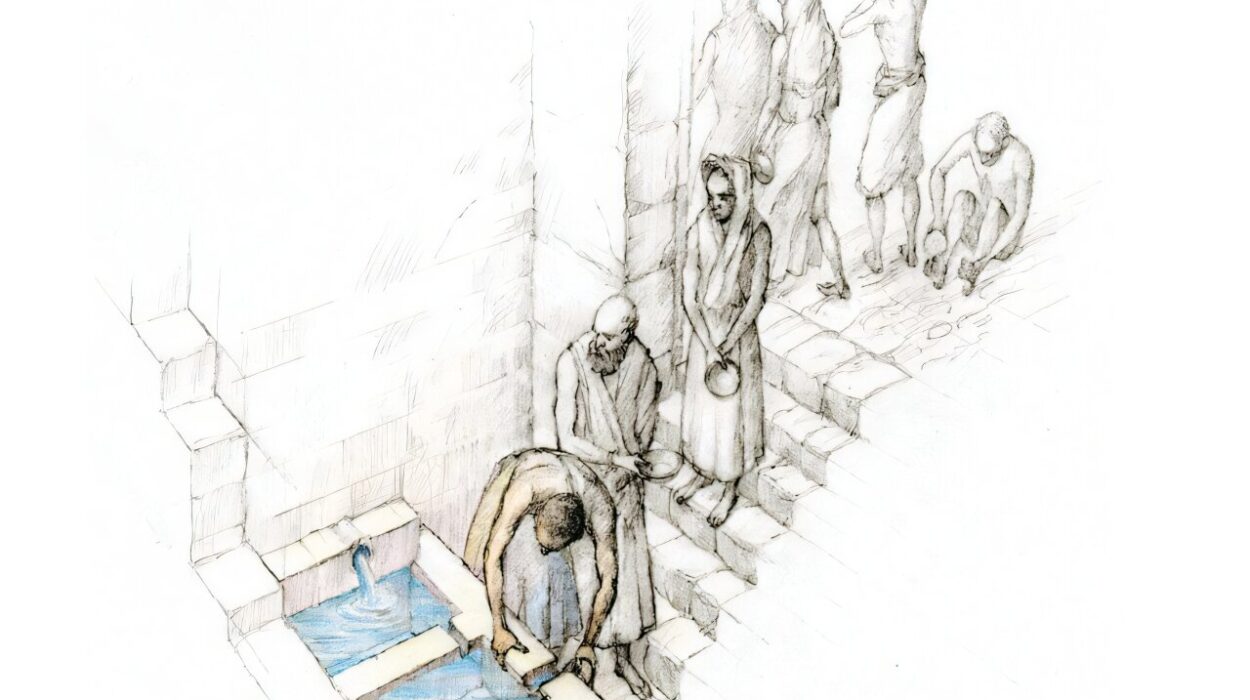

Such cellars rely on the earth’s thermal inertia: the deeper you go, the more constant the temperature becomes. In the summer, such spaces stay cool; in winter, they stay above freezing. For the Neolithic people of Falster, this would have been an engineering revelation—a primitive form of refrigeration. This single innovation could radically extend the shelf life of crops, dairy, and possibly even meat, making year-round survival far more secure.

If indeed this was a Neolithic root cellar, then it represents the earliest known structure of its kind in northern Europe—and possibly one of the earliest in the world.

Architectural Intelligence in Wood and Loam

The cellar, remarkable as it is, doesn’t stand alone. It was nestled within the remains of two large timber houses—phases of the same domestic structure rebuilt on the same footprint. Both buildings followed a recognizable architectural template from the Funnel Beaker tradition known as the Mossby-type, characterized by a double-span roof supported by internal wooden posts. This style provided durability, efficient space management, and thermal protection in the harsh northern climate.

The first structure had 38 post holes, and the second 35, indicating that these early farmers were not just skilled in tool-making and animal husbandry, but also in architectural planning. They understood load-bearing mechanics and materials. They had a clear sense of spatial organization.

Beneath their feet, the floors were made of compacted loam—a mix of clay, sand, and silt. Though this technique had been used elsewhere in the ancient world, its application in Neolithic Denmark represented a cutting-edge local adaptation. Loam floors are soft yet durable, thermally stable, and easy to repair. They were so effective, in fact, that they remained a flooring standard for centuries and are still used by over a billion people worldwide today.

A Fortress or a Farm? The Puzzle of the Post Rows

One of the most mysterious elements of the site is also one of the oldest: seven long rows of post holes, set apart from the dwellings and dating back to between 3600 and 3500 BC—a full 500 years before the houses were built. Their alignment and spacing suggest they once supported an exterior fence or boundary structure, but their purpose remains elusive.

Could these rows have delineated early pasture land? Were they part of an animal enclosure, or perhaps a defensive palisade to keep out wolves, bears, or even rival human groups? The presence of domesticated livestock in the Funnel Beaker economy makes animal fencing a real possibility. Yet the dating suggests that the site was strategically significant even before the houses were constructed.

If anything, this reinforces a compelling idea: this patch of ground was valuable—a hilltop with clear sightlines, near a water source but safely above the flood line. For centuries, people returned here to build, live, and likely survive the many challenges of early farming life.

The Artifact Trove: Flint, Pottery, and Ancient Curiosities

The excavation didn’t just yield architectural wonders—it uncovered a treasure trove of over 1,000 artifacts, each one a silent testimony to daily life, survival, and ritual.

Among the finds were flint tools—scrapers, blades, and arrowheads—painstakingly knapped with precision. There were pottery fragments, many bearing the characteristic funnel shape or decoration of the culture. Pottery in the Neolithic world wasn’t just utilitarian; it was also symbolic. These vessels held food, grain, water, and sometimes offerings to the dead.

Perhaps most enigmatic were the two fossilized sea urchins found among the cellar stones. Whether they were discarded curiosities, natural inclusions, or carried spiritual meaning is unclear. In many ancient cultures, fossils were seen as magical or symbolic—proof of past worlds, celestial influence, or earthly power.

A Leap in Food Preservation

The implications of the cellar go far beyond clever construction. In a world without iceboxes or canned goods, food storage was a daily concern that could mean the difference between feast and famine. The ability to build a subterranean, insulated storage facility represents a profound leap in technological and agricultural development.

With such a structure, vegetables could be stored for months, dairy products kept from spoiling, and possibly even meat preserved with smoke and cool conditions. It could allow food to be kept through harsh winters or to buffer against poor harvests—reducing the need for seasonal migration or foraging excursions.

The cellar would have served not just one family, but likely an entire household group or small clan, operating as a communal survival strategy.

What This Discovery Tells Us About Early Denmark

This site challenges long-standing assumptions that northern Europe’s early farmers were technologically unsophisticated. Too often, the Neolithic north is framed as trailing behind the more celebrated innovations of the Fertile Crescent or the Nile Valley.

But the Nygårdsvej site tells a different story—one of independent innovation. These people were not passive recipients of foreign ideas. They were experimenters, planners, and engineers in their own right.

They knew how to select strategic locations, build stable homes, insulate their food, and modify the land for human use. They understood long-term planning, architectural cycles, and the value of legacy construction.

In fact, what makes this site so vital is how ordinary it may have been for its time. If one such cellar existed, it is likely that others once did too—long since destroyed, buried, or overlooked.

Looking Ahead: Excavating the Unwritten Story

As with any major archaeological find, the discovery at Nygårdsvej 3 raises as many questions as it answers. Why was the site used and reused over such long time periods? What other structures once surrounded it? Was the cellar a rare innovation or part of a broader cultural trend that has simply not survived?

Future digs at the site may offer more clues. Stratigraphic layers, soil samples, or micro-remains like pollen and seeds could help reconstruct ancient diets, climate conditions, or seasonal activities. DNA analysis might reveal what animals were penned in the fenced area—or even what grains were stored in the cellar.

There is also the tantalizing possibility that ritual activity accompanied the use of the cellar. In many early societies, food and spirituality were deeply intertwined, with cellars doubling as sacred spaces for offerings, ceremonies, or ancestor veneration.

Conclusion: The Genius of the Forgotten Farmer

History often remembers the kings, the conquerors, the builders of empires and pyramids. But at Nygårdsvej 3, we catch a glimpse of something arguably more important: the brilliance of ordinary people. These were not royalty or priesthood. They were farmers, builders, and families—people who dared to tame a landscape, build homes from timber and soil, and devise technologies to sustain life in an unpredictable world.

The stone-paved root cellar of Falster may not be gilded or monumental. But in its quiet genius lies the fingerprint of human persistence—the echo of minds that reasoned, adapted, and engineered a way to thrive.

And perhaps, when we listen closely to the soil, we hear that echo still.

Reference: Marie Brinch et al, Stone-paved cellars in the stone age? Archaeological evidence for a neolithic subterranean construction from NygåRdsvej 3, Falster, Denmark, Radiocarbon (2024). DOI: 10.1017/RDC.2024.79