More than four thousand years ago, long before cities rose and written words captured history, people roamed the windswept plains and icy fjords of Patagonia — the rugged southern tip of South America. These were small groups of hunter-gatherers who survived through skill, resilience, and community. They tracked guanacos across open steppe, fished the cold waters, and endured harsh winters that tested every sinew of strength.

Now, thousands of years later, their bones are whispering stories — not just of survival, but of care, empathy, and humanity itself.

In a groundbreaking study published in the International Journal of Paleopathology, Dr. Victoria Romano and her team examined the remains of 189 individuals who lived during the Late Holocene — roughly between 4,000 and 250 years before the present. Their goal was not simply to understand how these people died, but how they lived together — how they helped one another through pain, injury, and recovery in a world without hospitals, antibiotics, or modern comforts.

Unearthing the Silent Evidence

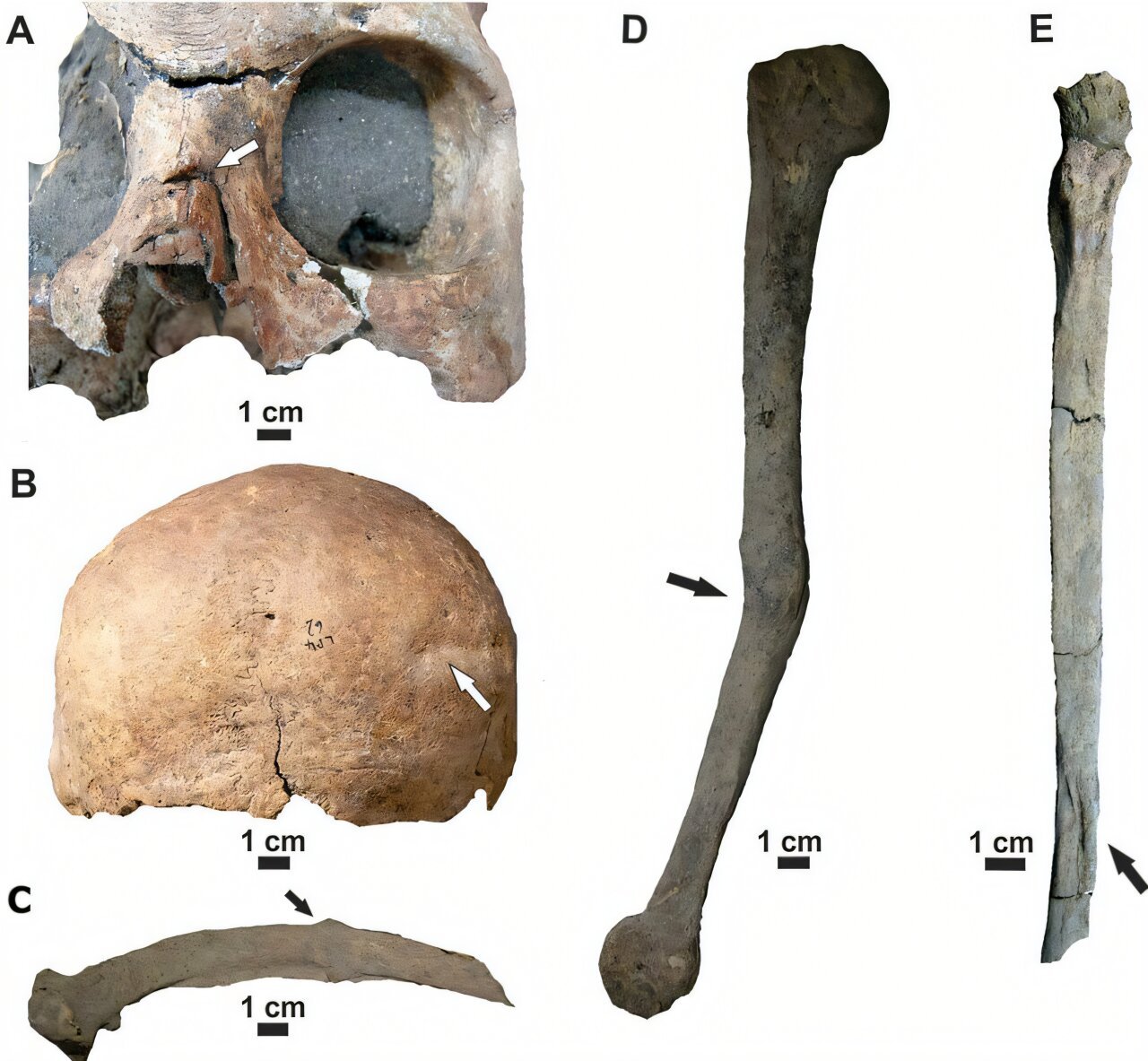

The research team analyzed 3,179 skeletal elements from 25 archaeological sites across Patagonia, each bone fragment a tiny fragment of human history. They discovered that around 20% of the individuals bore signs of trauma — fractures, breaks, or other skeletal injuries — ranging from mild to severe.

What was most striking, however, was that these injuries did not discriminate. Men and women had similar rates of trauma, and while adults were more often affected than children, both genders and age groups shared the burdens of physical hardship.

At first glance, it’s easy to imagine these injuries as the inevitable toll of life in a dangerous world — the result of falls, hunting accidents, or the rough landscapes of Patagonia. But Dr. Romano’s team looked deeper. They asked a profoundly human question: what did these injuries mean for the community around them?

Accidents or Violence? The Mystery of Broken Bones

Fractures, Dr. Romano explains, can be maddeningly ambiguous. A broken rib could result from a fall — or from a fight. A skull fracture might have come from slipping on rocks — or from the swing of a club. Without contextual evidence, distinguishing between accident and violence is almost impossible.

“We opted to consider that most injuries are likely attributable to accidents,” she said, noting that only two of the individuals had injuries that could be linked to violence — arrowheads lodged in bone. Even then, it remains unclear whether these were deliberate attacks or tragic accidents during hunting.

What emerges from the study, then, is not a picture of a violent people locked in constant conflict, but one of individuals who faced danger from their environment rather than from one another. These hunter-gatherers lived close to nature — and nature, though beautiful, was often unforgiving.

Degrees of Care: How Much Help Did They Need?

To understand how these communities responded to injury, Dr. Romano and her colleagues categorized trauma into three broad types: Mild Care, Moderate Care, and Intensive Care. Each level revealed not only the physical toll of injury but also the social response it demanded.

Mild Care represented the most common cases. These were injuries like minor cranial fractures, broken noses, or cracked ribs — painful, yes, but not life-altering. Such wounds likely healed in a few weeks with minimal disruption to group life. The injured person might have rested, relied on companions for food or protection, but soon returned to the rhythms of hunting and gathering.

Moderate Care was more serious, encompassing injuries that required months of healing. A broken arm or shoulder, for example, would have made tasks like tool-making, butchering, or carrying supplies impossible for some time. Recovery could take three to five months — a significant period in a nomadic lifestyle. During this time, the community would have needed to adapt: sharing resources, slowing travel, or assigning roles differently. These injuries reveal not only resilience, but cooperation — a willingness to support one another even when it meant changing the way the group functioned.

Then there were the Intensive Care cases — the most severe and socially demanding. Around 13% of the injuries fell into this category. These were traumas that could take half a year to heal or might leave the person permanently disabled.

A Story Written in Bone: The Healed Hip

Among the most moving discoveries was the skeleton of an individual with a severe hip injury — a deformity so striking that it immediately told a story. The ball of the thigh bone and the socket of the hip were misaligned and misshapen, evidence of either a violent fall or a developmental disease known as Legg-Calvé-Perthes, which interrupts blood flow to the hip joint and causes the bone to deteriorate.

What makes this case extraordinary is not the injury itself, but what came after. The bone showed clear signs of healing. This person lived for years — perhaps decades — after the injury occurred. In a mobile hunter-gatherer group, where survival depended on movement, this would have been nearly impossible without the help of others.

Someone must have carried them, tended their wounds, shared food, protected them during travel, and given them a reason to endure. Their survival is a testament not just to human adaptability, but to compassion — the quiet, often invisible force that binds communities together.

The Meaning of Care in a Mobile World

The idea of caregiving among ancient hunter-gatherers is both fascinating and challenging. Unlike sedentary farming communities, nomadic groups could not easily afford to stop for long periods. Every member had to contribute to hunting, foraging, or moving to new territories. Yet, as Dr. Romano’s study shows, care still happened — and not just in isolated cases.

Around one in five people bore evidence of trauma, and many of these injuries healed well, suggesting sustained, intentional support. This means that even in societies where survival demanded constant motion, empathy and social bonds played a vital role.

Caring for an injured person required planning and cooperation. The group would have needed to adjust their travel pace, share food, and perhaps modify shelter. Such acts of care reveal something deeply human — the instinct not only to survive as individuals but to ensure that others survived with us.

Violence, Accidents, and the Human Condition

The bones tell us much, but they do not speak plainly. They cannot say whether a fall was a misstep on slippery rocks or a push during conflict. Yet, the relative scarcity of violent injuries in this study suggests that cooperation, rather than aggression, defined these societies.

That doesn’t mean violence was absent — no human group has ever been entirely free of it — but it does suggest that the environment posed a far greater threat than one another. Broken bones, bruised joints, and fractures may have been the price of living in a raw, unpredictable landscape — climbing cliffs, hunting large prey, or crossing uneven terrain.

And when those accidents occurred, it was care — not abandonment — that shaped survival.

A New Perspective on Ancient Humanity

While archaeologists have long found isolated examples of care in prehistoric societies — individuals with healed injuries, evidence of disease management, or even primitive surgery — Dr. Romano’s work represents something new. It is the first population-level study to examine patterns of care among non-sedentary hunter-gatherers in Patagonia.

By looking beyond individual cases, the research paints a broader picture: care was not rare or exceptional. It was a fundamental part of how these communities functioned. The people of Patagonia did not merely endure their environment; they adapted to it together, carrying one another — sometimes literally — through hardship.

Echoes of Earlier Times

Dr. Romano notes that there are even hints of caregiving in earlier periods. A case from the Middle Holocene, for instance, involves a person with a severe heel bone injury who also showed signs of recovery — evidence that others must have helped them. These glimpses suggest that empathy and care are not recent human inventions. They are ancient, woven deep into the fabric of our species.

Future research may reveal whether these patterns of compassion changed over time — whether earlier or later populations cared differently, or whether this deep sense of mutual responsibility remained constant through millennia.

What the Bones Remind Us

The study of ancient trauma might seem clinical — measuring fractures, classifying injuries, cataloging bones. But beneath the data lies something profoundly emotional. Each healed bone is a record of kindness. Each recovered fracture is proof of patience and support.

In every rib that knitted itself back together, every hip that grew stable again, we find evidence of hands that helped, hearts that stayed, and a community that chose care over convenience.

The hunter-gatherers of Patagonia lived hard lives, but not loveless ones. Their endurance was not only biological but social — a reflection of the same compassion that still defines humanity today.

The Legacy of Ancient Compassion

We often think of progress in terms of technology or civilization — fire, tools, writing, cities. But perhaps the truest sign of human advancement lies elsewhere. It lies in the moment one person decides to help another who cannot walk. In the shared meal offered to someone too injured to hunt. In the willingness to carry, to wait, to heal together.

Dr. Romano’s study reminds us that the roots of empathy are as old as humanity itself. Long before hospitals and medicine, before nations and laws, there was care — the quiet, enduring act that allowed our ancestors to survive not just as individuals, but as communities.

In the ancient bones of Patagonia, we find not just traces of trauma, but echoes of tenderness. And through them, we glimpse the timeless truth that caring for one another is not just part of our history — it is the very reason we are still here.

More information: Victoria Romano et al, Bone trauma and interpersonal care among Late Holocene hunter-gatherers from Patagonia, Argentina, International Journal of Paleopathology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.ijpp.2025.08.003