Deep within the layers of English soil, tucked away in cemeteries that have rested quietly for over a millennium, lies a story not of isolation, but of a restless, interconnected world. For centuries, the history of early medieval England has been told through the ink of ancient manuscripts, painting pictures of sudden invasions and distinct waves of newcomers. However, a massive new study is shifting the perspective from the written word to the very molecules left behind by the people who lived it. By examining the chemical secrets hidden in human teeth, researchers have discovered that the English landscape was a bustling crossroads, welcoming travelers from the sun-drenched Mediterranean to the frozen reaches of the Arctic Circle.

The Whispers Trapped in Ancient Enamel

The journey to uncover these lost stories began at the Universities of Edinburgh and Cambridge, where a team of researchers embarked on the first large-scale analysis of its kind. They didn’t look for gold or jewelry; instead, they looked at tooth enamel. As a child grows, their teeth act like a biological diary, absorbing chemical signatures from the food they eat and the water they drink. These signatures are unique to specific geologies and climates. When a person moves to a new land and eventually passes away, their teeth remain as a permanent record of a childhood spent elsewhere.

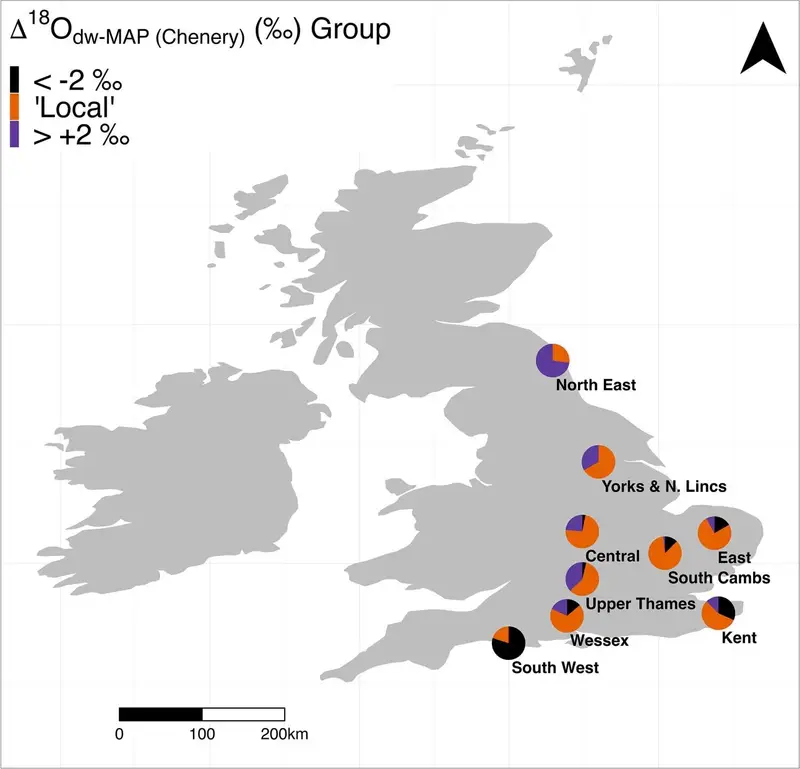

By analyzing more than 700 of these chemical signatures from skeletal remains dating between AD 400 and 1100, and comparing them with the ancient DNA of 316 individuals, the team began to bridge the gap between ancestry and actual physical movement. This period, stretching from the crumbling of Roman authority to the arrival of the Normans, has often been defined by “one-off” events—massive migrations or violent conquests. But the data told a different, more fluid story. It revealed a population in constant motion, where the act of crossing the sea or traversing the hills of Wales and Ireland was a common thread of life rather than a rare exception.

A Continuous Stream Across the Sea

One of the most striking revelations of the study was the sheer continuity of migration. Rather than seeing movement only during famous historical flashpoints, the researchers found that people were arriving in England steadily throughout the first millennium. It was a rhythmic, ongoing process that tied England into vast, large-scale networks. The data showed that these ancient communities were in “continual cross-cultural contact,” as Dr. Sam Leggett of the University of Edinburgh’s School of History, Classics and Archaeology explains. These networks were likely the engines behind the major social and cultural transformations that defined the era.

The research also painted a diverse picture of where these travelers originated. England was a destination for people from northwest Europe and the Mediterranean, but the reach extended even further. Some individuals bore the chemical marks of the Arctic Circle and beyond, suggesting that the early medieval world was far more connected than previously imagined. Even internal movement was significant, with clear evidence of people crossing into England from Ireland and Wales, weaving a complex tapestry of inhabitants that defied simple labels of “native” or “invader.”

When the Earth Grew Cold

The teeth did more than just track movement; they acted as ancient thermometers. The study captured the echoes of major climate events that shook the medieval world. One such event was the Late Antique Little Ice Age, a period of rapid and dramatic cooling that took place during the 6th and 7th centuries. The enamel of those buried during this time reflected the harsh realities of a changing environment. Interestingly, this period of cooling coincided with the arrival of newcomers from even colder regions, perhaps driven by the same environmental shifts that were reshaping the continent.

The researchers also noted signatures corresponding to the Medieval Climate Anomaly, showing how sensitive the human record is to the whims of the Earth’s climate. These findings suggest that migration wasn’t always driven by the ambition of kings or the hunger for land, but sometimes by the simple, urgent need to find a hospitable place to live as the world turned cold and the seasons shifted.

The Surprising Surge of the Seventh Century

While the movement of people was a steady drumbeat throughout the millennium, the data revealed an unexpected crescendo. Historians have long focused on the 5th and 6th centuries as the primary era of “Anglo-Saxon migrations,” but the bioarchaeological evidence pointed to a significant spike in mobility during the 7th and 8th centuries. This was a period well after the initial post-Roman transitions, yet it saw a surge in newcomers.

The study also looked at the roles of men and women in these migrations. While male migration appeared to be more prominent overall, women were far from stationary. The research highlighted notable female mobility, particularly into regions like Kent, Wessex, and the North East. This suggests that the movement of people was a family and community affair, with women playing a vital role in the settlement and cultural blending of early medieval society. Dr. Susanne Hakenbeck, of the University of Cambridge’s Department of Archaeology, noted the surprise of finding such high mobility so late in the period, remarking, “Our study shows that migration to Britain was fairly continuous throughout the first millennium. We didn’t expect to see a spike in mobility in the 7th and 8th centuries—well after the period of the so-called Anglo-Saxon migrations.”

Rewriting the Ancient Manuscripts

For centuries, our understanding of this era was dominated by texts like Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. These sources often focused on grand narratives of specific tribes or the deeds of great leaders. The researchers sought to see how these traditional stories aligned with the cold, hard evidence of biomolecular data. By taking a “big data” approach, they were able to test the old narratives against the lived experiences of hundreds of ordinary people.

The result is a more nuanced history. While the ancient texts capture part of the truth, the bioarchaeological findings show that the reality was much messier and more vibrant. England was never a fortress or an isolated island waiting for the next invasion. Instead, it was an active participant in a European and global community. As Dr. Hakenbeck, who co-authored the study with a fellow migrant, puts it: “This study… shows that Britain was never isolated from the continent.”

Why the Story of the Tooth Matters

This research matters because it fundamentally changes how we perceive the origins of a nation. It moves the conversation away from “one-off” invasions and toward a model of constant, cross-cultural exchange. By proving that migration was a normal, continuous part of life for nearly 700 years, the study dismantles the idea of an isolated or static society. It shows that the foundations of England were built by a diverse group of people—men and women, Mediterranean traders and Arctic travelers—who were all part of a massive, interconnected network.

Dr. Sam Leggett sums up the importance of this perspective: “The study took a ‘big data’ approach to assess the narratives around early medieval migration. We see here that migration was a consistent feature rather than just tied to one-off events, with evidence of communities in continual cross-cultural contact, tied into large-scale networks which may have contributed to the major socio-cultural changes we see throughout the period.” Ultimately, this research reminds us that human history is a story of movement, and that the “roots” of a culture are often found in the many paths that lead toward it.

More information: Sam Leggett et al, Large-Scale Isotopic Data Reveal Gendered Migration into Early Medieval England c AD 400–1100, Medieval Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1080/00766097.2025.2583016