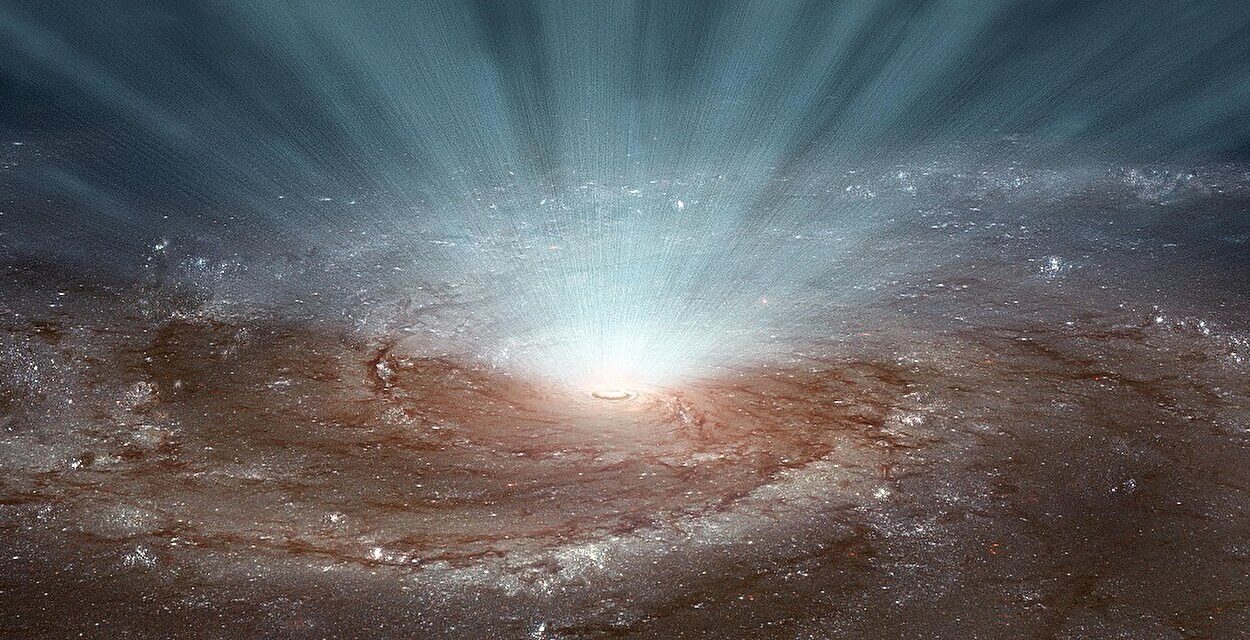

In the silent, vast expanse of the cosmos, our closest celestial neighbor hangs like a shimmering island of light. The Andromeda galaxy, also known to astronomers as Messier 31, is a massive barred spiral that mirrors our own Milky Way in many ways, yet it holds secrets within its swirling arms that we are only just beginning to map. Spanning about 152,000 light years and weighing in at a staggering 1.5 trillion solar masses, Andromeda is more than just a beautiful sight in a telescope; it is a laboratory for understanding how the universe builds its stars. To understand that process, scientists must look past the bright starlight and into the dark, freezing nurseries where galaxies keep their raw materials. These are the giant molecular clouds, the coldest and densest pockets of the interstellar medium.

These clouds are the ghosts of a galaxy’s birth, huge reservoirs of gas and dust left over from the ancient era when galaxies first coalesced. Composed mostly of molecular hydrogen, these complexes are often enormous, with those exceeding 100,000 solar masses earning the title of Giant Molecular Clouds, or GMCs. They range from 15 to 600 light years in diameter, acting as the quiet, frigid foundations upon which new suns are constructed. Because Andromeda is our nearest major neighbor, it offers a unique opportunity for humanity to peer into these nurseries with unprecedented detail. Recently, a team of astronomers led by Jairo Vladimir Armijos-Abendano from Cardiff University turned their focus toward these dark reservoirs, seeking to create a definitive atlas of the hidden architecture within the Andromeda galaxy.

Mapping the Invisible Architecture

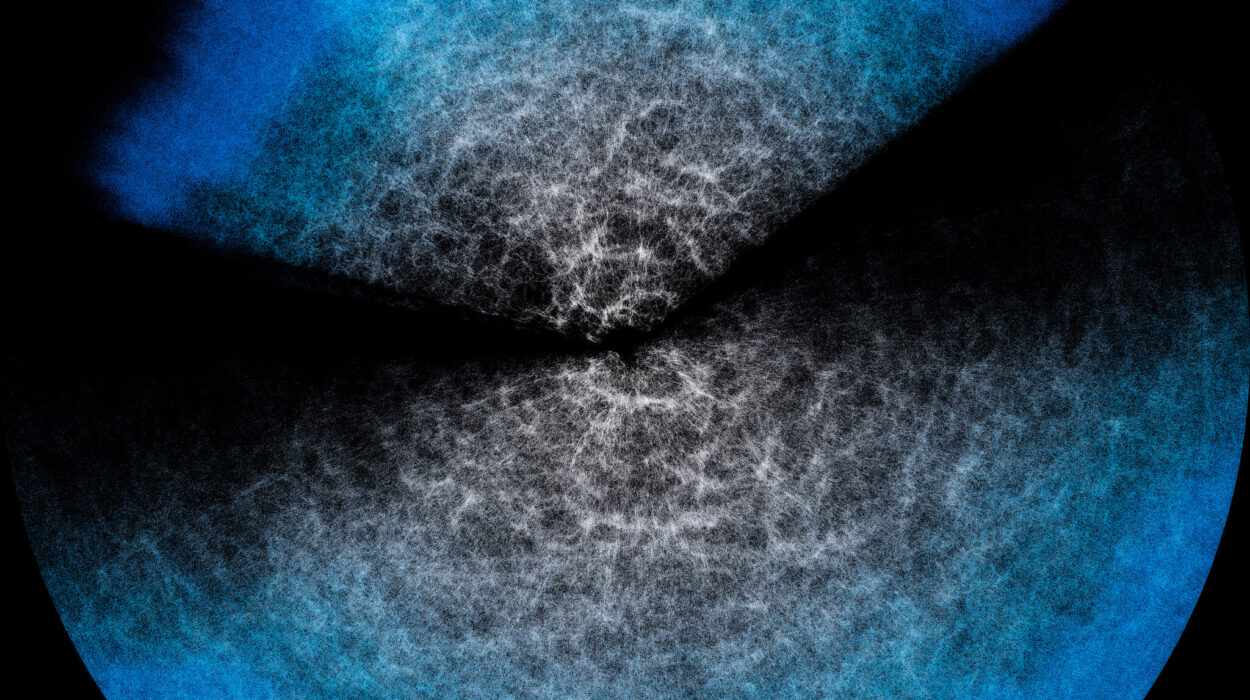

To see what is hidden in the dark, the researchers utilized the Combined Array for Research in Millimeter-wave Astronomy, known as CARMA. This sophisticated tool allowed them to peer through the galactic dust and identify the signatures of molecular gas that would otherwise remain invisible to the naked eye. The goal was ambitious: to build a comprehensive sample of GMCs by analyzing the data in a three-dimensional framework of position and velocity. As the researchers explained, “This work aims to create a sample of GMCs for M31 by applying a dendrogram to CARMA data in the position-position-velocity space, which will create the largest cloud sample for M31 so far.”

By using this “dendrogram” approach—a way of branching out data to see how structures are nested within one another—the team began to see the skeletal structure of Andromeda. They weren’t just looking for static dots on a map; they were looking for movement and mass. The results of this observational campaign, published recently on the pre-print server arXiv, revealed a hidden world far more populated than previously known. The team successfully identified 453 individual molecular clouds, a feat that established the largest cloud catalog ever created for the Andromeda galaxy. Beyond these individual clouds, they also discovered 35 sources that displayed multiple velocity components, which the team identified as complex systems where multiple clouds may be interacting or overlapping.

The Measured Pulse of Galactic Nurseries

As the researchers cataloged these hundreds of celestial objects, a physical profile of Andromeda’s nurseries began to emerge. The data showed that these clouds are truly titanic in scale. On average, the identified clouds possess a radius of approximately 72 light years and a mean mass of about 158,500 solar masses. These are not drifting wisps of smoke, but heavy, influential anchors of the interstellar medium. To understand if these clouds were stable or in the process of collapsing to form new stars, the team calculated their velocity dispersion—a measure of the internal movement of the gas—finding it to be roughly 2.8 km/s. This movement showed a slight, “weak anti-correlation” with how far the clouds were from the center of the galaxy.

One of the most vital questions in galactic archaeology is whether these clouds are simply passing through or if they are held together by their own gravity. By calculating the “virial parameters”—a mathematical way to weigh the energy of movement against the pull of gravity—the team found mean and median values of 2.0 and 1.4. This data point is crucial because it reveals the destiny of these gas giants. The researchers determined that about 66% of the clouds in the Andromeda galaxy are gravitationally bound. In the silent tug-of-war of deep space, these clouds have enough mass to hold themselves together, marking them as the definitive sites where future generations of stars will eventually ignite.

A Tale of Two Galaxies

With this massive new catalog in hand, the Cardiff University team was able to do something rarely possible: compare the “DNA” of Andromeda’s clouds with those found in our own Milky Way. While the two galaxies might look like siblings from a distance, the study found that their internal building blocks have distinct personalities. When the astronomers compared the size and mass values of the Andromeda clouds to those found in our home galaxy, they noticed a surprising discrepancy. In most regions of space, one might expect the mass of a cloud to grow in a predictable ratio relative to its size, but Andromeda follows its own rules.

The study revealed that the mass of the clouds in Andromeda does not scale with their radius in the same way it does in the Milky Way. There is a fundamental difference in the structural “slope” of these giant complexes. As the scientists concluded, “The slope of our size-mass relationship is shallower than those in clouds and cloud complexes of the Milky Way.” This finding suggests that even though Andromeda and the Milky Way are both large spiral galaxies, the environmental conditions or the history of their gas reservoirs have shaped their star-forming regions differently. Andromeda’s clouds are structured with a unique geometry that sets them apart from the nurseries we study closer to home.

Why the Secrets of Andromeda Matter

This research is a landmark in our understanding of the local universe. By creating the largest catalog of molecular clouds for our nearest neighbor, the team has provided a new “cloud atlas” that will serve as a foundation for future astronomical study. Understanding these clouds is the only way to truly understand the life cycle of galaxies. Since these clouds are the birthplaces of stars, knowing their mass, their stability, and how they are distributed tells us about the future of Andromeda—and, by extension, the future of our own cosmic neighborhood.

Furthermore, the discovery that Andromeda’s clouds scale differently than our own challenges the assumption that all spiral galaxies function identically under the hood. It reminds us that every galaxy has its own unique evolution and physical constraints. By documenting the 66% of clouds that are held together by gravity, scientists can now pinpoint exactly where the next surge of star birth will occur in Messier 31. This work bridges the gap between the massive, glowing scale of a galaxy and the cold, dark, microscopic interactions of gas and dust that make the universe’s grandest structures possible. Through the lens of CARMA and the dedication of the Cardiff team, the invisible reaches of Andromeda have finally been brought into the light.

More information: J. Armijos-Abendaño et al, Cloud Properties and Star Formation in M31, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2512.22698