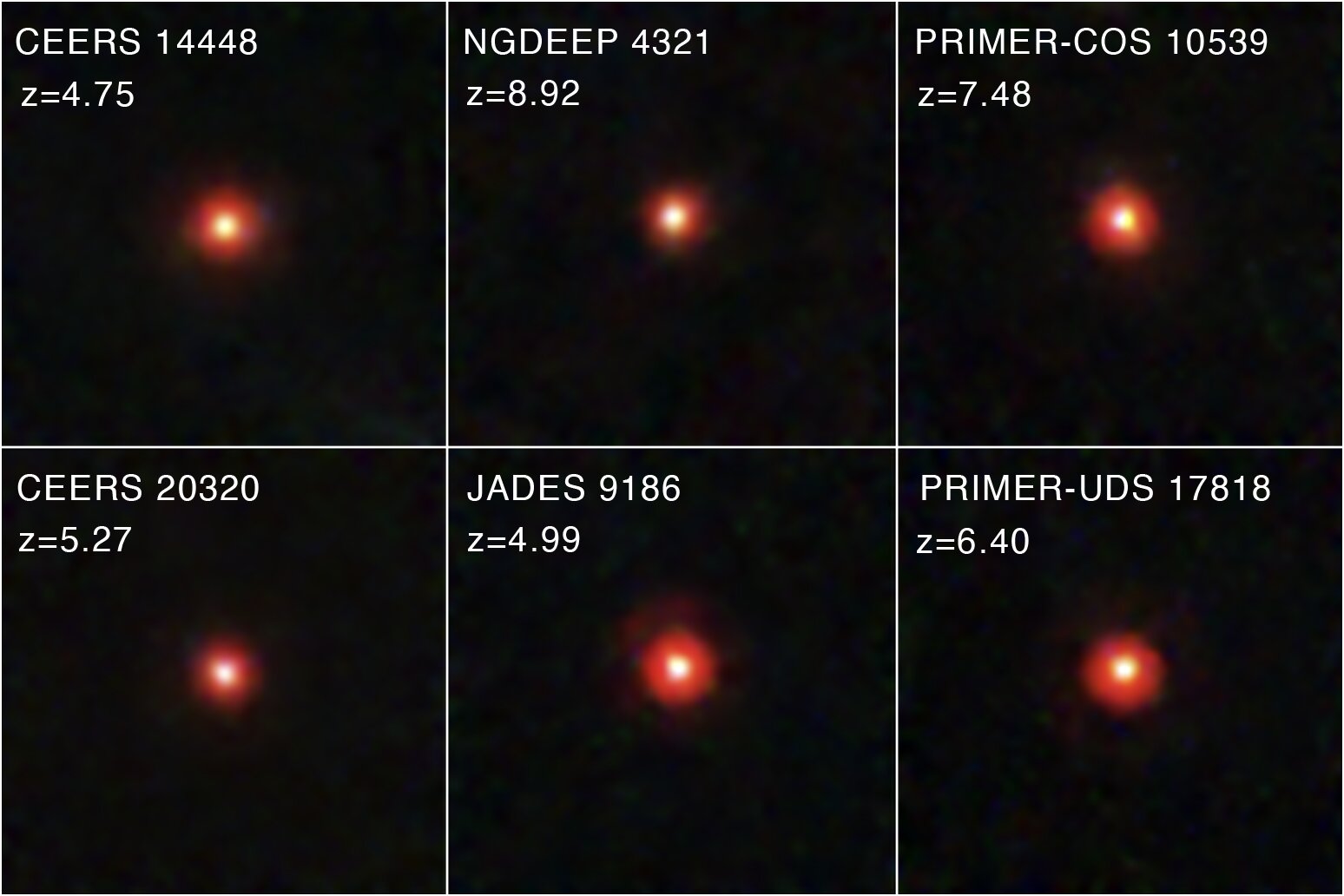

When the James Webb Space Telescope first opened its golden eye on the early universe, it did what it was built to do: it surprised everyone. Webb was meant to look back in time, to peer into an era not long after the Big Bang, when the first galaxies were just beginning to take shape. Instead of a quiet, orderly cosmic dawn, astronomers found something unexpected scattered across the deep field images: tiny, intensely bright, red-hued points of light.

They stood out immediately. Compact. Luminous. Uncomfortably early. Scientists gave them a simple, almost playful name that hinted at their strangeness: Little Red Dots.

At first glance, they looked like massive regions of star formation. That would have been exciting enough, but there was a problem. According to long-standing cosmological models, galaxies that large simply should not exist less than a billion years after the universe began. The red dots were appearing far too soon, shining with a confidence that theory said they hadn’t earned yet.

Something about them was wrong. Or perhaps, something about the models was.

A Cosmic Puzzle That Wouldn’t Sit Still

As more data came in, the early explanations began to fray. The Little Red Dots didn’t behave like star-forming galaxies. Their light carried signatures that didn’t match. They lacked clear features associated with active star birth. And yet they were abundant, compact, and evolving with redshift in ways that demanded a deeper explanation.

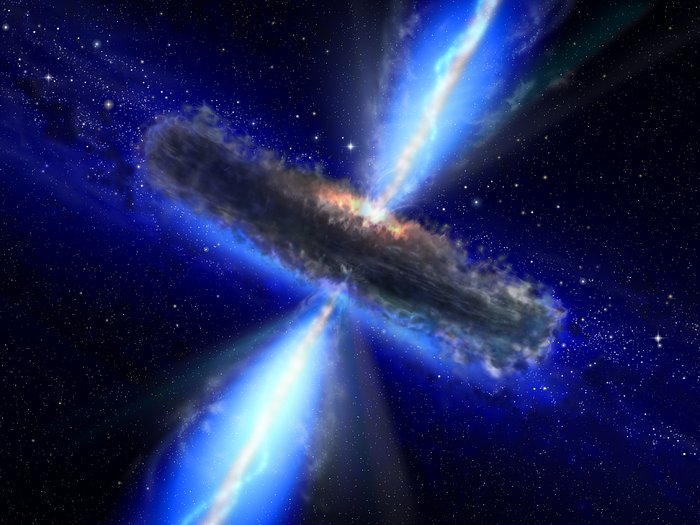

Another possibility emerged. What if these red points weren’t galaxies at all, but quasars? Quasars are the brilliant cores of galaxies powered by supermassive black holes, objects capable of outshining entire galaxies as matter spirals into them. That idea fit some of the brightness, but it raised an even bigger problem.

Supermassive black holes aren’t supposed to exist so early either.

Conventional theories say black holes begin as the remnants of massive stars. Those early stars, known as Population III, formed from hydrogen and helium alone, with almost no heavier elements. They were enormous, blisteringly hot, and lived fast, burning out in just 2 to 5 million years. When they collapsed, they left behind black holes. Over billions of years, through mergers and steady growth, those black holes could become massive.

Billions of years. Not a few hundred million.

The Little Red Dots were shining at a time when the universe was still young, and by all standard accounts, there simply hadn’t been enough time for black holes to grow that big.

This growing tension between observation and theory had been building quietly. Webb had just dragged it into the spotlight.

A Shortcut Through Cosmic Time

In a recent paper posted to the arXiv preprint server, a team of astronomers led by Fabio Pacucci of Harvard University offered a bold and elegant solution. The Little Red Dots, they argued, are not ordinary black holes grown slowly from stellar remains. They are something more direct, more dramatic.

They are Direct Collapse Black Holes, or DCBHs.

Unlike black holes born from dying stars, DCBHs are theorized to form when enormous clouds of cold hydrogen gas collapse all at once, skipping the star stage entirely. Instead of starting small and struggling to grow, these black holes are born already massive.

For decades, DCBHs have existed as a theoretical escape hatch, a way to resolve the long-standing problem of early supermassive black holes appearing too soon. But direct evidence had remained frustratingly out of reach.

Until now.

Pacucci, joined by Andrea Ferrara of the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa and Dale D. Kocevski of Colby College, set out to test whether actively accreting DCBHs could produce exactly what Webb was seeing.

Simulating a Black Hole’s First Breath

To explore this idea, the team turned to radiation-hydrodynamic simulations, powerful models that track both how gas falls into a black hole and how the radiation produced by that process reshapes the surrounding environment. These simulations don’t just calculate brightness; they follow a conversation between gravity and light.

As gas collapses onto a forming DCBH, it creates an extraordinarily dense cocoon. High-energy radiation produced near the black hole doesn’t escape freely. Instead, it is absorbed by the surrounding gas and reprocessed into ultraviolet and optical light. Over cosmic distances, that light stretches and shifts, eventually reaching Webb as infrared glow.

When the researchers transformed their simulations into mock observations, something remarkable happened. The simulated objects didn’t just resemble the Little Red Dots. They matched them.

The brightness. The color. The compact size. The way they evolved with redshift. Even their surprisingly weak X-ray emission, which had puzzled astronomers from the beginning, fell naturally out of the model.

Nothing needed to be forced. No special assumptions were required.

Every Clue Falling Into Place

One by one, the strange properties of the Little Red Dots stopped being strange.

The simulations reproduced the presence of metal and high-ionization lines in their light, without showing signs of active star formation. They explained why the objects appeared extremely compact, wrapped in dense gas that confined their emission. They even accounted for why these dots seemed overmassive compared to any stellar component they might host.

The models also revealed long-lived phases driven by radiation pressure, during which the black holes’ brightness varied over time. This variability, once another oddity, became a natural consequence of the environment surrounding a growing DCBH.

“All the puzzling properties of the LRDs are explained within a single, self-consistent framework,” Pacucci said. What made the model especially compelling was not just its explanatory power, but its simplicity. It built on decades of theoretical work describing how direct collapse black holes should form and evolve.

For a mystery that had challenged astronomers since Webb’s first deep images, the solution fit almost too well.

Webb’s Long-Sought Quarry

One of the primary scientific goals of the James Webb Space Telescope has always been to identify the universe’s first black holes and understand how they formed. For decades, astronomers had searched for signs of these primordial objects, suspecting they must exist but unable to catch them in the act.

According to Pacucci and his colleagues, Webb may finally be witnessing exactly that phase. Not the aftermath. Not distant descendants. But the moment when massive black hole seeds are forming and beginning to grow.

If the Little Red Dots are indeed accreting DCBHs, then Webb isn’t just observing ancient galaxies. It is watching the birth of black holes that would later shape galaxies across cosmic time.

That realization reframes the early universe. It suggests that black holes didn’t merely struggle to keep up with galaxy formation. They may have been there from the start, forming efficiently and early, setting the stage for everything that followed.

Why This Discovery Matters

The story of the Little Red Dots is more than a solved puzzle. It is a reminder of how science moves forward, not by defending old ideas, but by letting evidence lead the way.

By challenging established cosmological models, Webb has fulfilled its mission. What began as a confounding anomaly has become a window into one of the earliest and most elusive chapters of cosmic history. The Direct Collapse Black Hole scenario doesn’t just explain a curious observation. It offers a coherent picture of how the universe may have built its most powerful objects faster than anyone expected.

If confirmed through continued observation and analysis, this work reshapes our understanding of the universe’s first few hundred million years. It suggests that the seeds of today’s massive black holes were planted early, decisively, and efficiently, changing how galaxies evolved from the very beginning.

The Little Red Dots no longer look like cosmic mistakes. They look like signatures of a universe that knew how to build big things fast. And thanks to Webb, humanity is finally close enough to watch it happen.

Study Details

Fabio Pacucci et al, The Little Red Dots Are Direct Collapse Black Holes, arXiv (2026). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2601.14368