Ninety-one light-years away, in a patch of sky that looks calm and unremarkable to the naked eye, a modest star has been quietly tugging at its surroundings for billions of years. Its name is HD 176986, a K-type star smaller and cooler than our Sun, glowing at an effective temperature of 4,931 K. At first glance, it seems like just another stellar neighbor. But patience, it turns out, changes everything.

Astronomers have been watching this star for nearly two decades, listening closely to the faint, rhythmic wobbles in its light. Those wobbles are the subtle fingerprints of orbiting worlds, each one pulling gently on the star as it circles. With enough time and enough precision, those whispers become a story.

Now, that story has grown richer. Using years of accumulated observations from two of the world’s most sensitive planet-hunting instruments, astronomers have uncovered a new planet hiding in plain sight. The discovery, detailed in a study published on January 28 in Astronomy & Astrophysics, adds a third known world to this nearby system and reveals how patience can transform scattered data into planetary truth.

Two Known Worlds, Then Something More

The tale of HD 176986 as a planetary system began in 2018, when astronomers confirmed the presence of two tightly orbiting super-Earth exoplanets. These planets, named HD 176986 b and HD 176986 c, move quickly around their star, completing an orbit in just 6.5 days and 16.82 days, respectively.

They are heavy worlds. Even the lighter of the two, HD 176986 b, carries several times the mass of Earth. The second planet, HD 176986 c, is heavier still. These were not delicate, Earth-like spheres drifting serenely in space. They were dense, compact planets locked in close embrace with their star, bathed in heat.

Yet something about the data never fully settled. The star’s motion hinted at more than just these two companions. The signals were faint, stretched out over long timescales, easy to miss if one was not looking carefully enough.

Instead of moving on, a team of astronomers led by Nicola Nari of the Teide Observatory decided to listen longer.

Watching a Star for Nearly 19 Years

The key to this discovery was time. A lot of it.

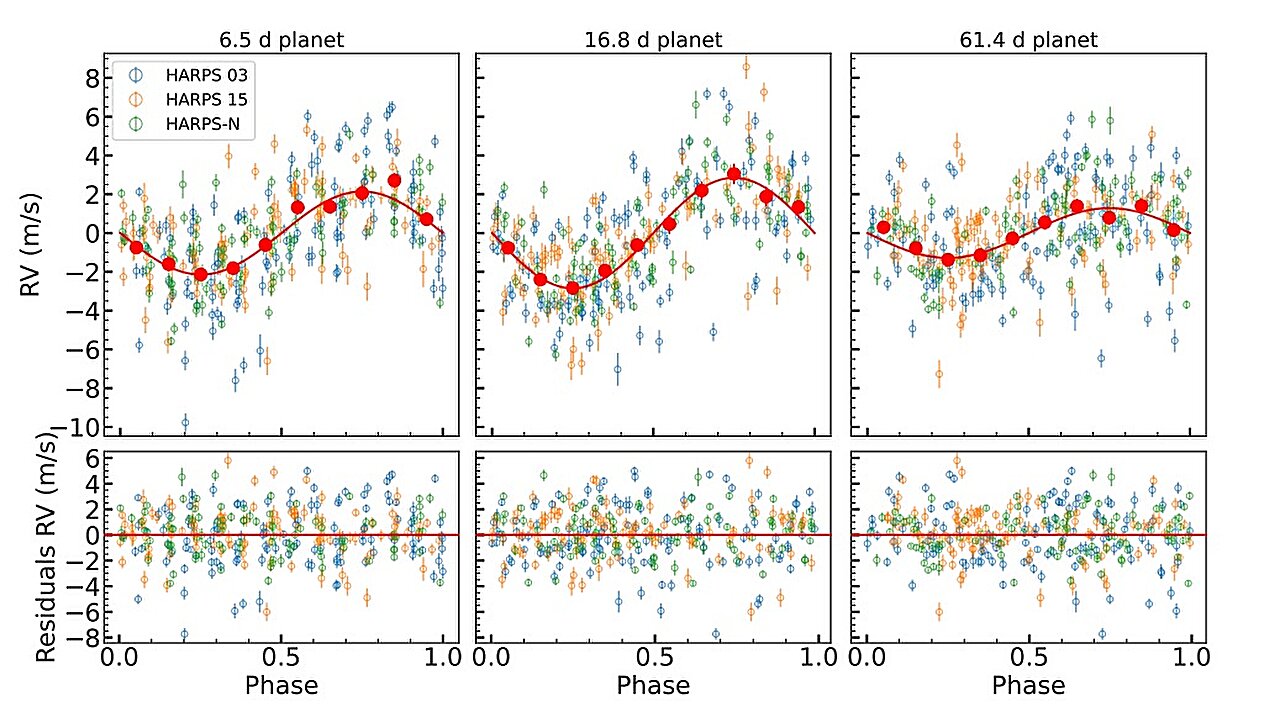

The research team returned to the system armed with a much larger dataset than ever before. Observations that once spanned 13.2 years were extended to 18.6 years, growing from 234 nights of data to 330 nights. This was not a single telescope staring relentlessly into the dark, but a coordinated effort across hemispheres.

They used the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS), mounted on the ESO 3.6-meter Telescope in Chile, and its northern twin, HARPS-N, installed on the Galileo National Telescope in Spain. Together, these instruments can detect stellar motions as small as a human walking pace, even from light-years away.

The observations were carried out as part of the Rocky Planets in Equatorial Stars (RoPES) program, a long-term effort designed to find planets without preconceptions, letting the data speak for itself.

And eventually, it did.

The Slow Reveal of a Hidden Planet

Buried in the extended dataset was a new, repeating signal. Unlike the frantic rhythms of the inner planets, this one unfolded slowly and steadily. It pointed to a planet orbiting HD 176986 once every 61.38 days, far enough from the star to escape earlier detection.

This newly revealed world has been designated HD 176986 d.

It circles its star at a distance of about 0.28 AU, significantly farther out than its two known siblings. Its minimum mass is estimated at 6.76 Earth masses, placing it firmly in the category of super-Earths or possibly sub-Neptunes, depending on its composition.

At this distance, the planet’s calculated equilibrium temperature is 363 K. While still far warmer than Earth, it occupies a different thermal regime than the scorched inner worlds, hinting at a more complex structure to the system than previously known.

This planet had been there all along, patiently tracing its orbit while astronomers slowly gathered enough evidence to recognize its presence.

Refining the Portrait of Familiar Worlds

The discovery of HD 176986 d did more than add a new name to the system. It sharpened the picture of the planets astronomers already knew.

With the longer observational baseline, the team refined the characteristics of HD 176986 b. Its orbital period is now measured at 6.49 days, slightly adjusted from earlier estimates. Its minimum mass has been refined to 5.36 Earth masses, and its equilibrium temperature stands at a scorching 767 K.

HD 176986 c also emerged with clearer definition. It completes an orbit every 16.81 days, carries a minimum mass of 9.75 Earth masses, and maintains an equilibrium temperature of 558 K.

Together, the three planets form a compact but layered system. Two hot, massive worlds cling close to their star, while a third, slightly cooler companion traces a wider path beyond them.

Why Long Searches Matter

What makes this discovery stand out is not just the planet itself, but the way it was found.

The researchers emphasize that the detection of HD 176986 d demonstrates the power of blind search radial velocity surveys like RoPES. These surveys do not rely on short observational campaigns or assumptions about where planets should be. Instead, they commit to the long haul, collecting data year after year until subtle signals rise above the noise.

This approach is particularly important for finding planets with orbital periods longer than 50 days, which can easily slip through the cracks of shorter studies. Without nearly two decades of patient observation, HD 176986 d would have remained invisible.

The findings also highlight why long-term radial velocity surveys are essential for exploring the habitable zones of K-type and G-type stars. Planets in these regions often orbit farther out, moving more slowly and leaving fainter signatures in the data. Detecting them requires not just precision, but endurance.

A System That Teaches Us to Wait

HD 176986 is about 4.3 billion years old, roughly the same age as our own solar system. It has spent all that time hosting its planets, their gravitational dances unchanged by whether or not anyone was watching.

Now, thanks to years of careful observation, we see the system more clearly. What once looked like a simple pair of close-in super-Earths has revealed itself as a richer, more layered planetary family.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research matters because it shows how planets can hide in well-studied systems, waiting for astronomers willing to look longer and listen more carefully. It reminds us that discovering new worlds is not always about building bigger telescopes or chasing dramatic signals, but about committing to time, consistency, and precision.

By uncovering HD 176986 d, astronomers have demonstrated that nearby stars may host more planets than we currently realize, especially worlds with longer orbits that are harder to detect. Each such discovery expands our understanding of how planetary systems form and evolve, and brings us closer to mapping the true diversity of planets in our galactic neighborhood.

In the quiet wobble of a modest star, recorded night after night across nearly twenty years, a new world finally stepped into view.

Study Details

Nicola Nari et al., The RoPES project with HARPS and HARPS-N II. A third planet in the multi-planet system HD 176986, Astronomy & Astrophysics (2026). DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202557287.