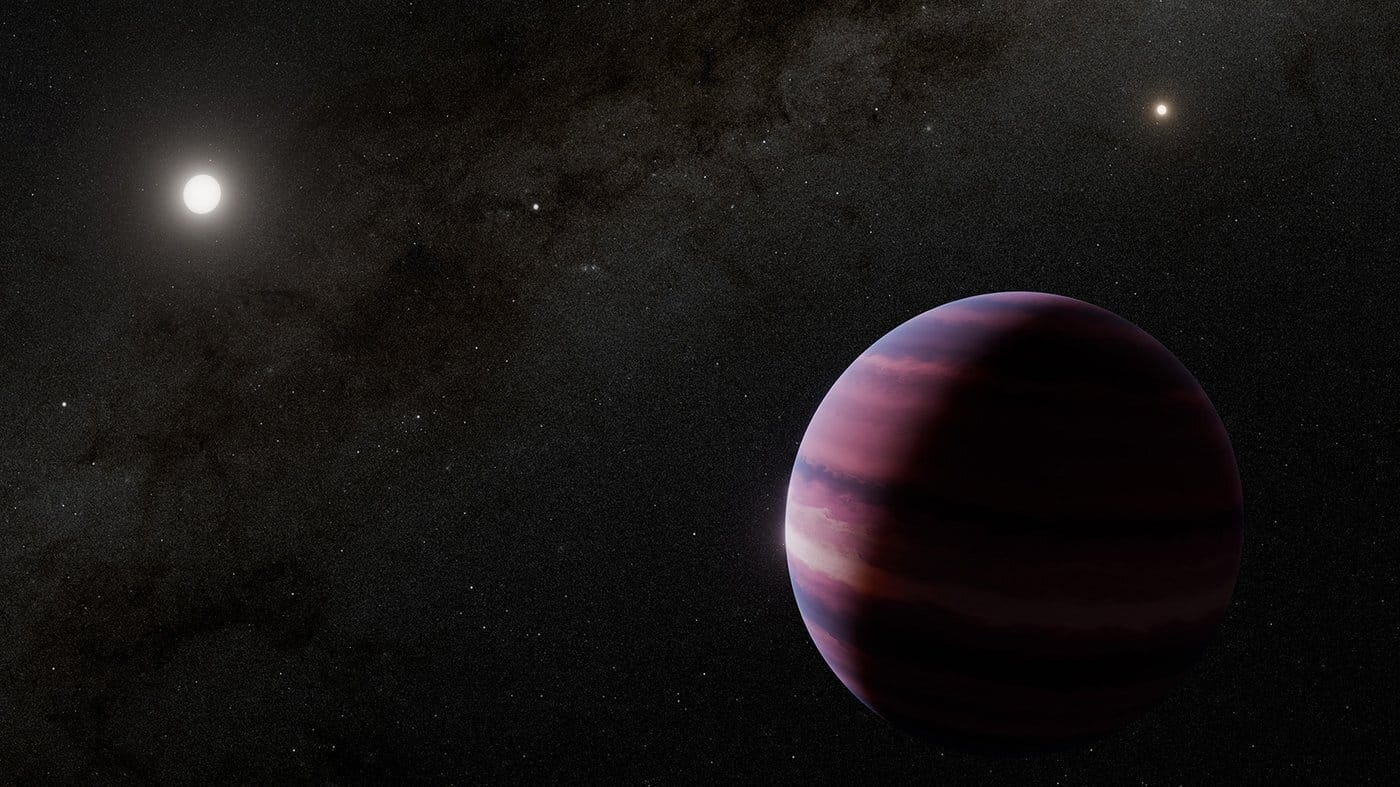

Just four light-years from Earth—practically next door in cosmic terms—astronomers using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope may have found compelling evidence for a planet orbiting one of the most intriguing stars in the sky. The Alpha Centauri system, a triple-star ensemble long considered a prime target in the search for worlds beyond our solar system, has now revealed its most tantalizing hint yet: a giant planet circling Alpha Centauri A, the closest sun-like star to our own.

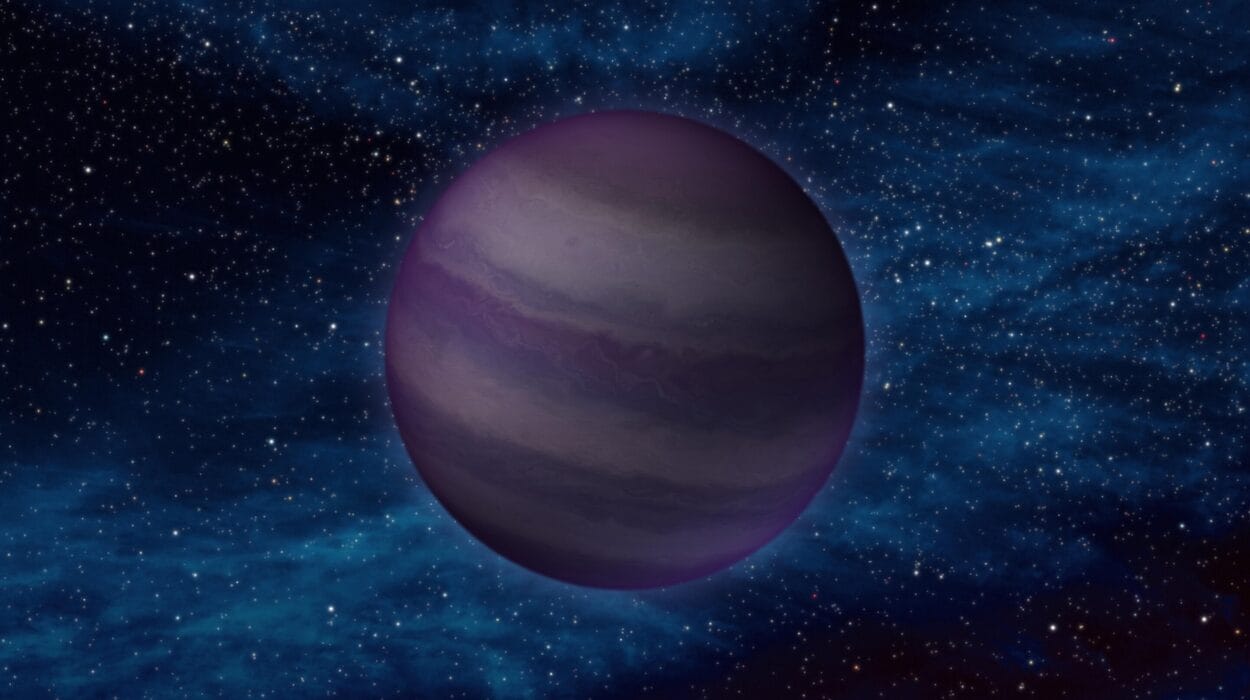

If confirmed, this world would not only become the closest known planet in the habitable zone of a sun-like star—it would also mark a milestone in the art of directly imaging exoplanets, a notoriously difficult feat. While the candidate appears to be a gas giant too large and inhospitable for life as we know it, its discovery would still be a game-changer for our understanding of planetary formation in complex star systems.

“This is as close as it gets for us to study another sun-like star and its planets in detail,” says Charles Beichman, executive director of the NASA Exoplanet Science Institute at Caltech and senior scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). “The system’s proximity means we can collect more precise data than almost anywhere else beyond our own solar system.”

The Stars Next Door

Alpha Centauri is a stellar family of three. Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B form a tight binary pair—both bright, yellowish stars similar in size and temperature to our Sun. The third member, Proxima Centauri, is a faint red dwarf orbiting far out from the main pair. Proxima already boasts three confirmed planets, including Proxima b, a rocky world in its habitable zone. But until now, the sun-like stars at the system’s heart have kept their secrets.

Finding planets around Alpha Centauri A or B has been exceptionally difficult. These stars are both dazzlingly bright and relatively close to each other, meaning their combined glare overwhelms the faint light of any orbiting worlds. Even with advanced telescopes, picking out a planet’s delicate signal is like spotting a firefly next to a pair of floodlights.

That is why this potential discovery—made possible by Webb’s advanced mid-infrared vision—is so significant.

Peering Through the Glare

In August 2024, a team led by Caltech graduate student Aniket Sanghi and Beichman turned Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) toward Alpha Centauri A. They used a special tool called a coronagraphic mask, which blocks out a star’s light, allowing astronomers to directly photograph the much dimmer objects nearby. Direct imaging is rare in exoplanet science because it’s technically demanding; most exoplanets are detected indirectly, through the way they tug on their stars or dim their light during transits.

The challenge was immense. Alpha Centauri A’s brightness was only part of the problem—its companion star, Alpha Centauri B, was close enough to add its own glare. The team had to carefully subtract out the light from both stars, leaving behind the faintest possible signature of a hidden world.

What they found was a dot—more than 10,000 times fainter than Alpha Centauri A—nestled about two astronomical units (AU) from the star. For scale, 1 AU is the distance between Earth and the Sun. This planet candidate sits twice that distance away, roughly where the asteroid belt lies in our own solar system. In Alpha Centauri A’s case, that location falls squarely within its habitable zone—the region where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist on a planet’s surface.

A Giant in the Habitable Zone

Based on its brightness in the mid-infrared, the candidate appears to be a gas giant similar in mass to Saturn. Its orbit, the researchers believe, is elliptical, meaning it sweeps through a wide swath of the habitable zone during each revolution. That’s good news for imaging purposes but bad news for smaller, Earth-like planets that might otherwise occupy the same region—such a giant could gravitationally destabilize them.

While gas giants in habitable zones cannot host life on their surfaces, they might have moons with conditions suitable for biology. In our own solar system, Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus are icy worlds with subsurface oceans, proving that life-friendly environments can exist far from the warmth of a star.

“This is the first time we may have imaged a planet around a star so much like our own Sun in both age and temperature,” Sanghi explains. “Its very presence in such a dynamic binary system forces us to rethink how planets survive and evolve in complex stellar neighborhoods.”

A Cautious Confirmation Process

The team is not calling this a confirmed discovery—yet. Follow-up Webb observations failed to spot the planet, but the researchers believe that’s because it may have moved too close to its star in its elliptical orbit to be visible. Computer simulations suggest this is entirely plausible.

Future observations will be critical. The Webb telescope is expected to revisit Alpha Centauri in the coming years, and NASA’s upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, launching by May 2027, will bring even more powerful planet-hunting capabilities. These next-generation observations could confirm the candidate’s existence, refine its orbit, and reveal more about its composition.

“If confirmed, this would be the closest directly imaged planet to its star that we’ve ever seen,” says Beichman. “The implications for exoplanet imaging, and for our ability to study nearby planetary systems, are enormous.”

Why This Matters

The search for exoplanets is ultimately a search for perspective. Each discovery tells us something about the diversity of worlds in our galaxy, and about where our own solar system fits into that vast catalog. Finding a gas giant in the habitable zone of Alpha Centauri A may not mean we’ve found another Earth, but it does mean we’re closing in on the ability to find one.

Alpha Centauri’s proximity makes it a natural laboratory. Even a gas giant there could help astronomers develop the techniques they’ll need to spot and study smaller, potentially habitable planets around other sun-like stars.

And perhaps most importantly, the fact that such a planet might exist in our nearest stellar neighbor is a reminder that the universe is full of surprises—sometimes hiding right next door.

“This is why we look,” Sanghi says. “Because just when we think we understand how planets form and survive, the cosmos gives us something completely unexpected.”

More information: Aniket Sanghi et al, Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. II. Binary Star Modeling, Planet and Exozodi Search, and Sensitivity Analysis, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2508.03812

Charles Beichman et al, Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2508.03814