Close your eyes for a moment and think about your earliest memory. Perhaps it’s a warm summer afternoon, the scent of fresh-cut grass filling the air, or the feel of your mother’s hand as she guided you across the street. Now imagine recalling the name of your first teacher, or the taste of a dish you haven’t eaten in decades. These acts seem effortless—instant mental travel to a moment long past—but what’s actually happening in your brain is nothing short of extraordinary.

Every time you remember, you are reactivating patterns of electrical and chemical activity that have been shaped, modified, and stored inside an unimaginably complex network of neurons. The process is not like retrieving a file from a computer. It’s more like conducting a symphony, where different instruments (brain regions) join in at precisely the right moments, weaving together the sensory, emotional, and factual threads that make a memory come alive.

To understand how the brain stores and retrieves memories, we have to take a journey into its hidden architecture—a journey that begins with the birth of a memory and ends with its vivid replay in the theater of your mind.

The Architecture of Memory: A Network, Not a Filing Cabinet

It’s tempting to think of memory as a filing system where each experience is stored in its own folder, waiting to be pulled out when needed. In reality, memory is distributed. The visual parts of a scene are stored in visual areas, the sounds in auditory areas, the emotional tone in limbic circuits, and so on. What we call a “memory” is a reactivation of these scattered traces, bound together by a network of connections.

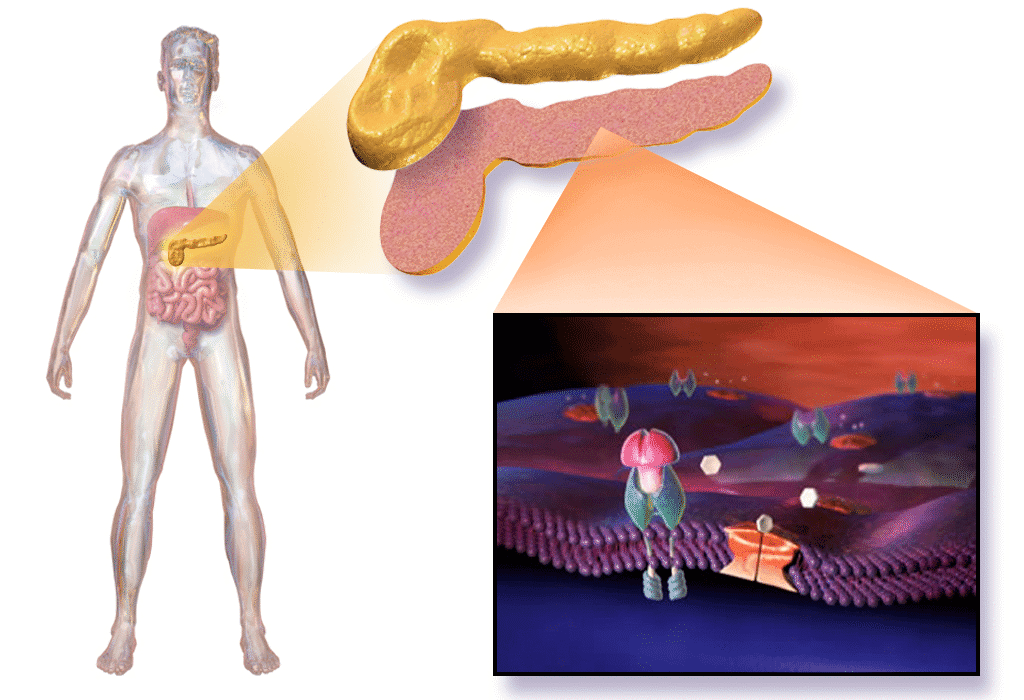

At the heart of this system is the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped structure buried deep within the medial temporal lobe. The hippocampus doesn’t store memories forever, but it acts as a temporary hub that links together the various components of an experience. Think of it as the conductor who knows how to bring in each section of the orchestra.

Surrounding the hippocampus are regions like the entorhinal cortex, perirhinal cortex, and parahippocampal cortex—gateways that feed information into and out of the hippocampus. The amygdala, an almond-shaped structure nearby, tags memories with emotional weight, making some moments unforgettable while others fade quickly.

In the cortex itself—spread across the folds and grooves of the brain—lie the long-term storage sites. This is where the patterns of connections between neurons, strengthened or weakened over time, encode the details of our lives.

From Experience to Encoding: How Memories Begin

A memory starts with perception. Light hits your eyes, sound waves vibrate in your ears, pressure sensors in your skin detect texture and temperature. These sensory signals are converted into electrical impulses that travel to the brain’s primary sensory cortices. Here, the raw data is processed—edges and colors in vision, pitch and rhythm in hearing, and so on.

From there, the brain’s associative areas begin to integrate the sensory inputs into a coherent scene. If the experience is novel, emotionally charged, or significant in some way, the hippocampus gets involved. Neurons in the hippocampus begin to form patterns of activation that correspond to the experience.

This process of initial storage is called encoding. It depends heavily on attention. You cannot encode what you do not focus on—this is why you might forget someone’s name moments after meeting them if you’re distracted. The neurotransmitter acetylcholine plays a key role here, enhancing the hippocampus’s ability to encode new information.

Strengthening the Trace: Synaptic Plasticity and Memory Formation

The physical basis of memory lies in changes to the connections between neurons—what neuroscientists call synaptic plasticity. One of the most studied forms of plasticity is long-term potentiation (LTP). In LTP, repeated activation of a synapse makes it more responsive in the future. The signal between two neurons grows stronger, like a path in the woods becoming clearer with repeated use.

This strengthening involves a cascade of molecular events. When a neuron is activated, calcium ions flow into the cell, triggering enzymes that alter receptor density and protein synthesis. Over time, structural changes occur: dendritic spines—the tiny protrusions where synapses form—may grow, and new synaptic connections may sprout.

These changes are not confined to the hippocampus. As a memory consolidates, the cortical areas that processed its original sensory inputs undergo their own synaptic modifications. In a way, the memory trace becomes woven into the brain’s physical fabric.

The Role of Sleep: Memory’s Silent Guardian

One of the most powerful, yet invisible, influences on memory storage is sleep. During certain stages of sleep—especially slow-wave sleep—the hippocampus “replays” patterns of neural activity from the day. This replay is believed to help transfer memories from short-term hippocampal storage to long-term cortical storage.

Think of it as the brain’s nightly filing process. While you sleep, your brain sifts through the day’s events, strengthening the important connections and pruning the irrelevant ones. Dreams may be a byproduct of this process, fragments of memory and emotion bubbling up as the neural circuits shuffle and reorganize.

Research has shown that people who sleep after learning retain information far better than those who stay awake. Even short naps can enhance memory, provided they include the right stages of sleep.

Retrieval: The Art of Mental Time Travel

Storing a memory is only half the story. Retrieval is the act of reassembling the scattered components of a memory into a coherent whole. When you try to remember, your brain doesn’t pull out a single “file.” Instead, a cue—something you see, hear, or think—activates a pattern of neurons in the hippocampus, which in turn activates the cortical areas that stored the details.

This is why context is so powerful. Smelling a certain perfume can instantly transport you to a long-forgotten evening. Walking into your childhood home might flood you with memories of playing in the backyard. The cue triggers a cascade of neural activations, and the brain reconstructs the experience.

But retrieval is not perfect. Each time you recall a memory, you are reconstructing it, not replaying it like a video. Details can change subtly, influenced by your current mood, beliefs, and new experiences. In this way, memory is both reliable and fragile—a living, evolving record rather than a static archive.

The Fragility of Memory: Forgetting and Distortion

Forgetting is not a failure of the brain—it is an essential feature. Our neural capacity is not infinite, and the ability to forget irrelevant or outdated information is as important as remembering what matters. Memories fade when the synaptic connections that support them weaken over time, a process known as decay. Interference from new learning can also disrupt old memories.

Sometimes, memories are not just lost but distorted. The same flexibility that allows us to update memories with new information also leaves them vulnerable to error. Psychologists have shown how easily false memories can be implanted—by suggesting details that never occurred, people can become confident in events that never happened.

This malleability has evolutionary advantages. It allows us to adapt our recollections to current needs, updating our knowledge of the world. But it also raises profound questions about eyewitness testimony, historical record, and personal identity.

Emotion and Memory: The Amygdala’s Influence

Emotion can be a powerful amplifier of memory. The amygdala, which processes fear and pleasure, interacts closely with the hippocampus during encoding. When something emotionally significant happens—whether it’s a moment of joy or terror—the amygdala releases neuromodulators like norepinephrine that enhance memory consolidation.

This is why you may vividly remember where you were during a major personal or historical event, but struggle to recall what you had for lunch last Tuesday. Emotional salience signals the brain that this memory is important and should be preserved.

However, extreme emotional arousal can sometimes impair memory. Trauma can lead to fragmented or incomplete recollections, as in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In such cases, the normal integration of sensory and contextual information may be disrupted, leaving the person with intrusive fragments rather than coherent narratives.

Working Memory: The Brain’s Mental Workspace

Not all memory is about the past. Working memory is the ability to hold and manipulate information in the present—remembering a phone number long enough to dial it, or keeping track of where you are in a conversation. This involves the prefrontal cortex interacting with other brain regions to maintain temporary representations.

Working memory is capacity-limited, typically able to hold about four to seven items at a time. It is essential for reasoning, decision-making, and learning, acting as a bridge between perception and long-term storage.

Lifelong Changes in Memory: From Childhood to Old Age

Memory is not static across the lifespan. In childhood, the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex are still developing, which explains why early memories (before about age three) are rare—a phenomenon known as childhood amnesia. As we grow, our memory systems become more sophisticated, and we gain the ability to form richer, more detailed recollections.

In adulthood, memory peaks in many respects, though certain types—like the recall of new names or arbitrary facts—may begin to decline in middle age. In older age, changes in brain structure and function can lead to reduced encoding and retrieval efficiency. However, emotionally rich and well-practiced memories often remain robust.

Conditions like Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias disrupt memory by damaging neurons and synapses, particularly in the hippocampus and associated regions. These illnesses highlight just how deeply memory is tied to our sense of self. To lose memory is not just to lose facts—it is to lose parts of who we are.

The Mystery That Remains

Despite remarkable advances in neuroscience, memory still holds mysteries. We can describe the processes of encoding, consolidation, and retrieval, and we can identify the brain regions and molecular mechanisms involved. Yet the subjective experience of remembering—the vividness, the emotional resonance, the sense of “traveling” in time—remains elusive.

Why certain moments are etched into us while others vanish is still not fully understood. Nor do we yet know how to perfectly repair damaged memories or prevent the distortions of false recall. Memory is both a scientific puzzle and a deeply human phenomenon, shaped by biology but also by meaning, culture, and personal narrative.

Living with the Gift of Memory

Our ability to store and retrieve memories is more than a biological function—it is the thread that weaves our life’s story. Without memory, we could not learn, recognize loved ones, or plan for the future. Memory allows us to savor joy long after the moment has passed and to learn from mistakes without repeating them endlessly.

But memory is not about clinging to the past. It is about carrying forward what matters, letting go of what does not, and allowing ourselves to be shaped—but not trapped—by our experiences. In the end, memory is the mind’s most precious treasure, a constantly evolving mosaic of who we have been, who we are, and who we might yet become.