The universe has a secret, and it is becoming harder to ignore. Astronomers have known for decades that space is expanding, stretching the distances between galaxies like an ever-rising cosmic tide. Yet the exact speed of this expansion has become one of the most stubborn mysteries in modern science. Two different ways of measuring it yield two different answers, and the disagreement is so persistent that it has earned a name whispered with both frustration and excitement: the Hubble tension.

For years, researchers have wondered whether the problem lies in the data, in the methods, or in the universe itself. Now a team that includes scientists from the University of Tokyo believes they may have taken an important step toward clearing the fog. Their new work suggests that the tension might not be an illusion born of flawed measurements. It might be real. And if it is real, it could open the door to physics we have never seen before.

A New Path Through the Cosmic Maze

To find clarity in this cosmic disagreement, the team looked far past familiar tools like supernovas and Cepheid stars. These traditional markers, known as distance ladders, have helped astronomers estimate the expansion rate—roughly 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec—but doubts have lingered about hidden sources of error.

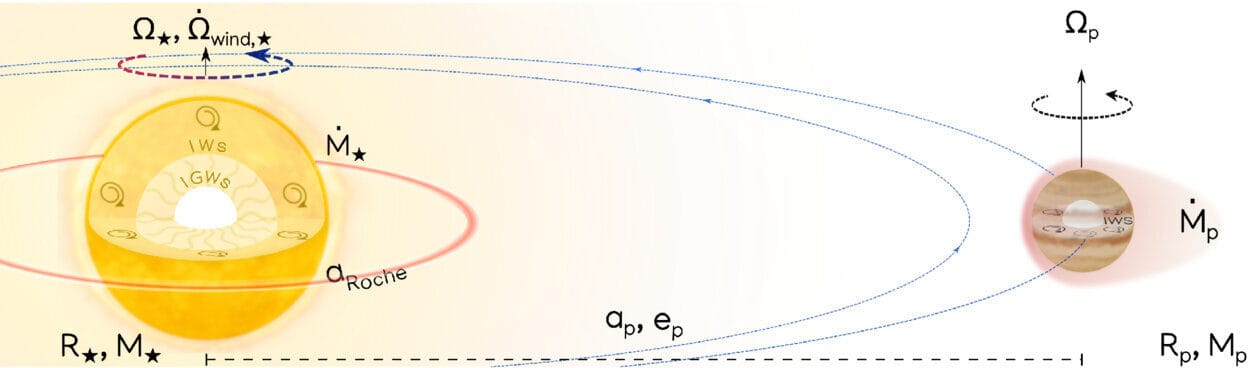

Instead of relying on exploding stars, Project Assistant Professor Kenneth Wong and postdoctoral researcher Eric Paic helped demonstrate a technique that turns the universe’s most massive galaxies into natural laboratories. They used a phenomenon called time-delay cosmography, a method that plays with the very pathways that light chooses as it crosses space.

“To measure the Hubble constant using time-delay cosmography, you need a really massive galaxy that can act as a lens,” said Wong.

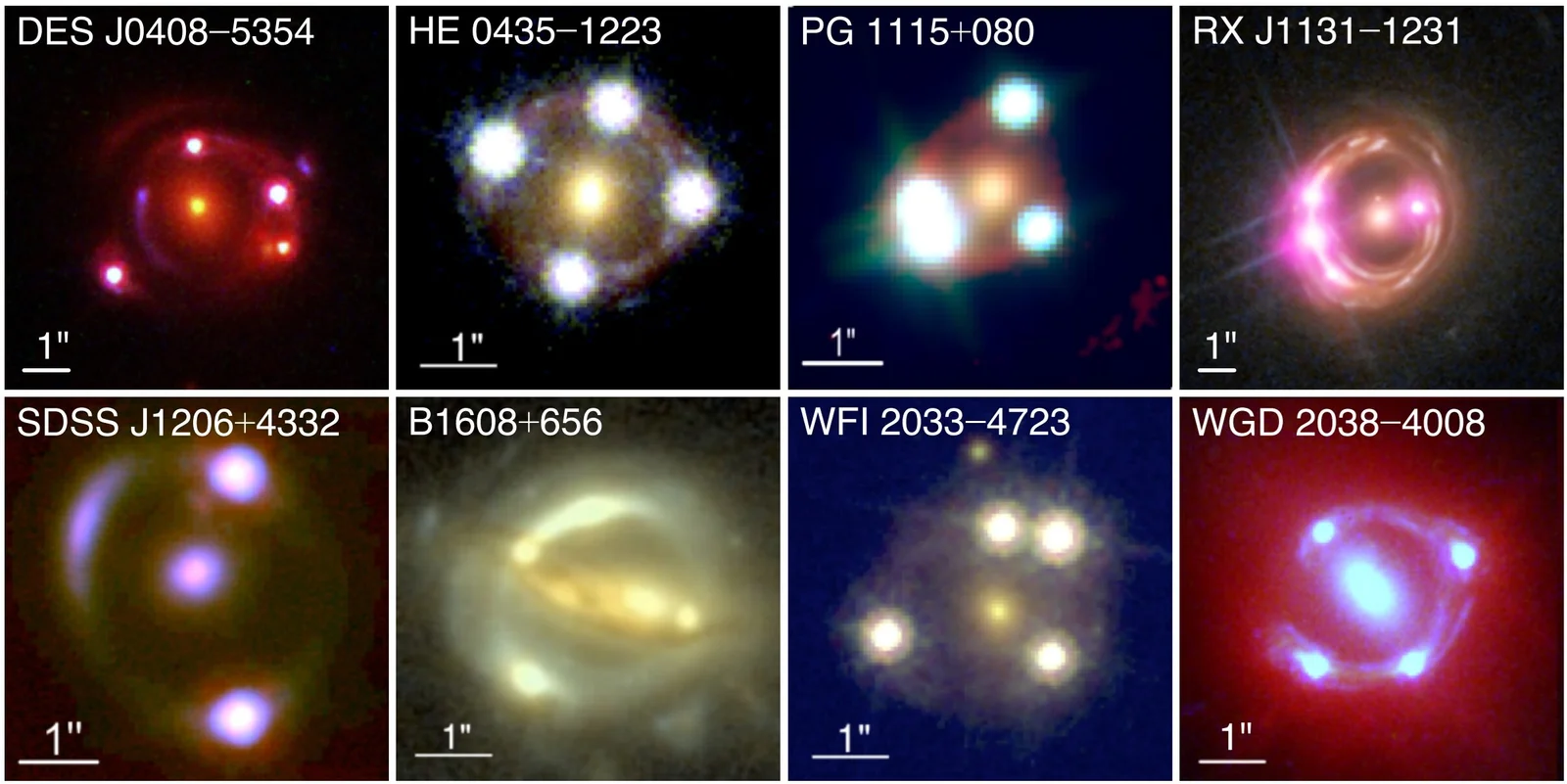

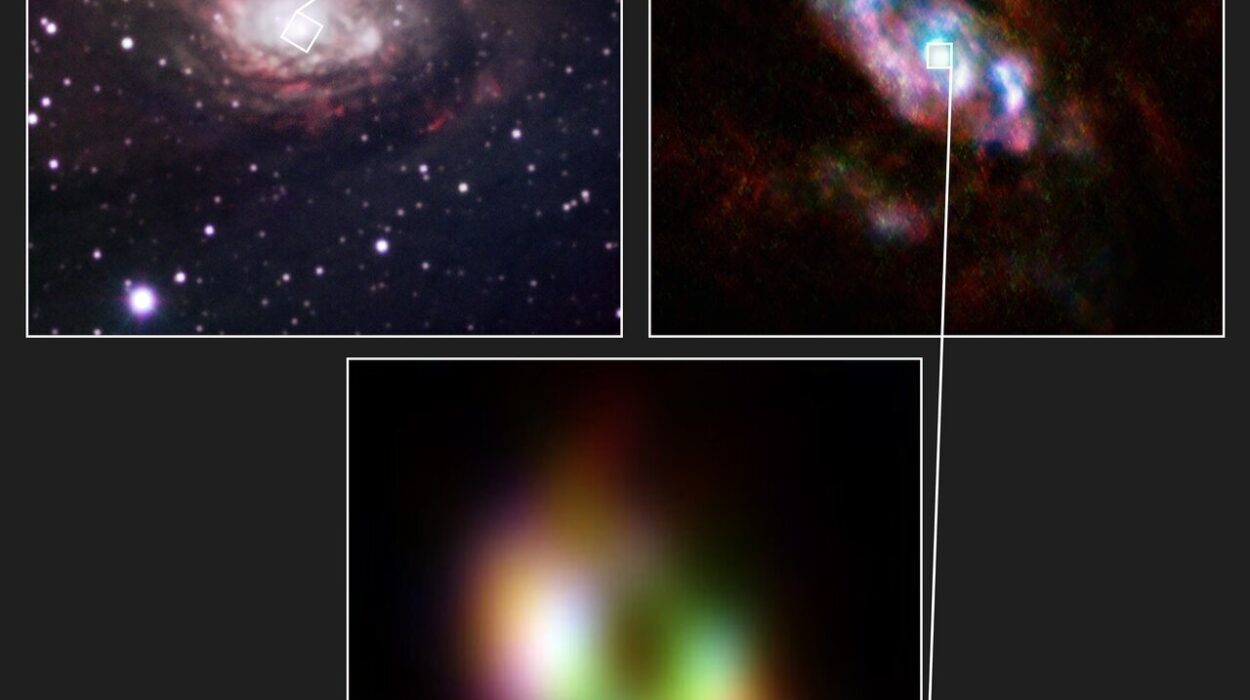

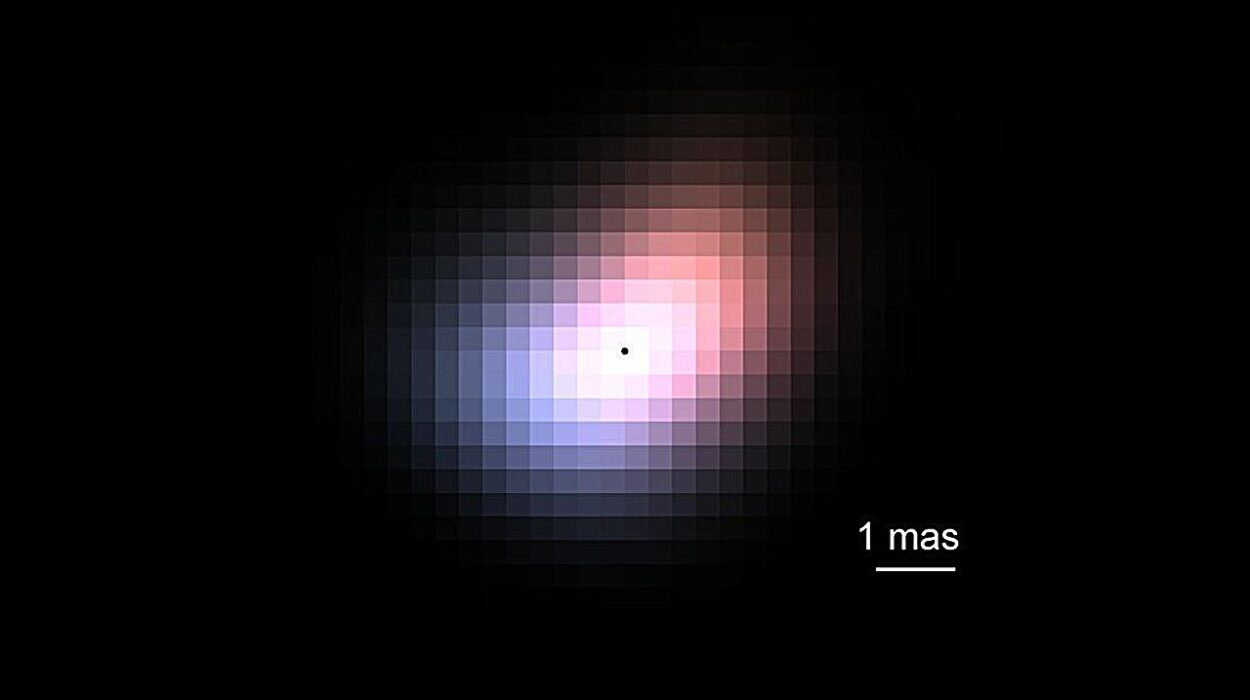

In these rare cosmic alignments, a distant quasar sits behind a giant galaxy. The galaxy’s gravity pulls on the quasar’s light, bending it and splitting it into multiple images. Each image has traveled a slightly different route—some longer, some shorter—before arriving on Earth. Those paths are like alternate roads through the universe, each telling a slightly different story about distance and time.

“If the circumstances are right, we’ll actually see multiple distorted images, and each will have taken a slightly different pathway to get to us, taking different amounts of time,” Wong explained.

The quasar behind the lens flickers unpredictably, as quasars often do. By watching how the flickers arrive at different times in the duplicate images, the team can measure the delays between the paths. Those delays, combined with detailed analyses of the lensing galaxy’s mass, reveal something precious: a new way to calculate how fast the universe is expanding.

“The Hubble constant we measure is well within the ranges supported by other modes of estimation,” Wong said.

When Two Histories of the Universe Collide

But the story becomes more tangled when the new method is compared with the universe’s earliest light. The cosmic microwave background, a faint glow left behind by the Big Bang, tells a different story about the expansion rate. According to measurements of this primal radiation, the universe expands not at 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec, but closer to 67.

This mismatch is the heart of the Hubble tension, and it has unsettled cosmologists for years. Either the early universe and the modern universe tell incompatible stories—or something about our methods is wrong.

Wong and Paic’s team may be sharpening the picture.

“Our measurement of the Hubble constant is more consistent with other current-day observations and less consistent with early-universe measurements. This is evidence that the Hubble tension may indeed arise from real physics and not just some unknown source of error in the various methods,” said Wong.

And here lies the intriguing part. Their method is independent—untethered from both supernova-based approaches and early-universe calculations. If those other tools hide systematic errors, this one should not share them.

“Our measurement is completely independent of other methods, both early- and late-universe, so if there are any systematic uncertainties in those methods, we should not be affected by them,” Wong said.

The Long Road Toward Certainty

Yet even with the promise of independence, the work is far from finished. Paic emphasizes that refining the method is just the beginning.

“The main focus of this work was to improve our methodology, and now we need to increase the sample size to improve the precision and decisively settle the Hubble tension,” said Paic.

Right now their precision is about 4.5 percent. To truly resolve the cosmic argument, they need to reach around 1 to 2 percent. It is a steep goal, but not unreachable.

The team used eight time-delay systems in their latest study, each featuring a galaxy lens and a quasar blazing behind it. They also drew on fresh observations from cutting-edge telescopes, including the James Webb Space Telescope. The next steps involve expanding the sample and fine-tuning the models that describe how mass is spread within the lensing galaxies.

“One of the largest sources of uncertainty is the fact that we don’t know exactly how the mass in the lens galaxies is distributed. It is usually assumed that the mass follows some simple profile that is consistent with observations, but it is hard to be sure, and this uncertainty can directly influence the values we calculate,” Wong said.

Every improvement, every new lens system, every refined measurement pulls the universe’s expansion story into sharper focus.

Why This Mystery Matters

The stakes of this research stretch far beyond a single number. Whether the universe expands at 67 or 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec is not just a technical curiosity. It is a cornerstone of our understanding of the cosmos.

If the tension is a measurement error, then the universe may be simpler than it currently appears. But if the tension is real—if the early universe and the modern universe disagree in a fundamental way—then something is missing from our understanding of cosmic evolution.

“The Hubble tension matters, as it may point to a new era in cosmology revealing new physics,” Wong said.

This work reflects that possibility, built on decades of collaboration between observatories around the world. Time-delay cosmography does not rely on traditional distance ladders, nor does it rely on relic radiation from the dawn of time. It cuts its own path through the cosmos, illuminating a new way forward.

If the universe truly carries two incompatible histories, this method may be one of the keys to discovering why. It may reveal a hidden chapter in cosmic evolution, a chapter that could reshape our understanding of matter, energy, or the structure of space itself.

The universe has been whispering its secret for years. With each new analysis of these delayed pathways of ancient light, we are learning to listen more carefully.

More information: TDCOSMO 2025: Cosmological constraints from strong lensing time delays, Astronomy & Astrophysics (2025). DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202555801